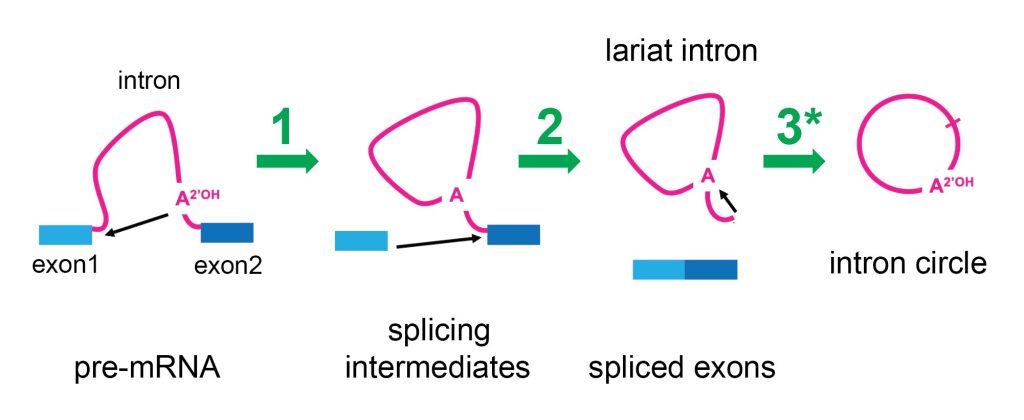

Shown is the splicing pathway. The pre-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) has exons (blue) and introns (pink). The spliceosome (not shown) was known to catalyze two chemical reactions (black arrows) in a two-step process (green arrows labeled 1 and 2) that splice the exons together and removes the intron as a lariat. This study demonstrates that after splicing is finished, the spliceosome is still active and can convert the lariat intron into a circle using a third reaction (green arrow 3) marked by an asterix. Credit: Manuel Ares, UC Santa Cruz

Although you may not appreciate them, or have even heard of them, throughout your body, countless microscopic machines called spliceosomes are hard at work. As you sit and read, they are faithfully and rapidly putting back together the broken information in your genes by removing sequences called “introns” so that your messenger RNAs can make the correct proteins needed by your cells.

Introns are perhaps one of our genome’s biggest mysteries. They are DNA sequences that interrupt the sensible protein-coding information in your genes, and need to be “spliced out.” The human genome has hundreds of thousands of introns, about 7 or 8 per gene, and each is removed by a specialized RNA protein complex called the “spliceosome” that cuts out all the introns and splices together the remaining coding sequences, called exons. How this system of broken genes and the spliceosome evolved in our genomes is not known.

Over his long career, Manny Ares, UC Santa Cruz distinguished professor of molecular, cellular, and developmental biology, has made it his mission to learn as much about RNA splicing as he can.

“I’m all about the spliceosome,” Ares said. “I just want to know everything the spliceosome does—even if I don’t know why it is doing it.”

In a new paper published in the journal Genes and Development, Ares reports on a surprising discovery about the spliceosome that could tell us more about the evolution of different species and the way cells have adapted to the strange problem of introns. The authors show that after the spliceosome is finished splicing the mRNA, it remains active and can engage in further reactions with the removed introns.

This discovery provides the strongest indication we have so far that spliceosomes could be able to reinsert an intron back into the genome in another location. This is an ability that spliceosomes were not previously believed to possess, but which is a common characteristic of “Group II introns,” distant cousins of the spliceosome that exist primarily in bacteria.

The spliceosome and Group II introns are believed to share a common ancestor that was responsible for spreading introns throughout the genome, but while Group II introns can splice themselves out of RNA and then directly back into DNA, the “spliceosomal introns” that are found in most higher-level organisms require the spliceosome for splicing and were not believed to be reinserted back into DNA. However, Ares’s lab’s finding indicates that the spliceosome might still be reinserting introns into the genome today. This is an intriguing possibility to consider because introns that are reintroduced into DNA add complexity to the genome, and understanding more about where these introns come from could help us to better understand how organisms continue to evolve.

Building on an interesting discovery

An organism’s genes are made of DNA, in which four bases, adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T) are ordered in sequences that code for biological instructions, like how to make specific proteins the body needs. Before these instructions can be read, the DNA gets copied into RNA by a process known as transcription, and then the introns in that RNA have to be removed before a ribosome can translate it into actual proteins.

The spliceosome removes introns using a two-step process that results in the intron RNA having one of its ends joined to its middle, forming a circle with a tail that looks like a cowboy’s “lariat,” or lasso. This appearance has led to them being named “lariat introns.” Recently, researchers at Brown University who were studying the locations of the joining sites in these lariats made an odd observation—some introns were actually circular instead of lariat shaped.

This observation immediately got Ares’s attention. Something seemed to be interacting with the lariat introns after they were removed from the RNA sequence to change their shape, and the spliceosome was his main suspect.

“I thought that was interesting because of this old, old idea about where introns came from,” Ares said. “There is a lot of evidence that the RNA parts of the spliceosome, the snRNAs, are closely related to Group II introns.”

Because the chemical mechanism for splicing is very similar between the spliceosomes and their distant cousins, the Group II introns, many researchers have theorized that when the process of self-splicing became too inefficient for Group II introns to reliably complete on their own, parts of these introns evolved to become the spliceosome. While Group II introns were able to insert themselves directly back into DNA, however, spliceosomal introns that required the help of spliceosomes were not thought to be inserted back into DNA.

“One of the questions that was sort of missing from this story in my mind was, is it possible that the modern spliceosome is still able to take a lariat intron and insert it somewhere in the genome?” Ares said. “Is it still capable of doing what the ancestor complex did?”

To begin to answer this question, Ares decided to investigate whether it was indeed the spliceosome that was making changes to the lariat introns to remove their tails. His lab slowed the splicing process in yeast cells, and discovered that after the spliceosome released the mRNA that it had finished splicing introns from, it hung onto intron lariats and reshaped them into true circles. The Ares lab was able to reanalyze published RNA sequencing data from human cells and found that human spliceosomes also had this ability.

“We are excited about this because while we don’t know what this circular RNA might do, the fact that the spliceosome is still active suggests it may be able to catalyze the insertion of the lariat intron back into the genome,” Ares said.

If the spliceosome is able to reinsert the intron into DNA, this would also add significant weight to the theory that spliceosomes and Group II introns shared a common ancestor long ago.

Testing a theory

Now that Ares and his lab have shown that the spliceosome has the catalytic ability to hypothetically place introns back into DNA like their ancestors did, the next step is for the researchers to create an artificial situation in which they “feed” a DNA strand to a spliceosome that is still attached to a lariat intron and see if they can actually get it to insert the intron somewhere, which would present “proof of concept” for this theory.

If the spliceosome is able to reinsert introns into the genome, it is likely to be a very infrequent event in humans, because the human spliceosomes are in incredibly high demand and therefore do not have much time to spend with removed introns. In other organisms where the spliceosome isn’t as busy, however, the reinsertion of introns may be more frequent. Ares is working closely with UCSC Biomolecular Engineering Professor Russ Corbett-Detig, who has recently led a systematic and exhaustive hunt for new introns in the available genomes of all intron-containing species that was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) last year.

The paper in PNAS showed that intron “burst” events far back in evolutionary history likely introduced thousands of introns into a genome all at once. Ares and Corbett-Detig are now working to recreate a burst event artificially, which would give them insight into how genomes reacted when this happened.

Ares said that his cross-disciplinary partnership with Corbett-Detig has opened the doors for them to really dig into some of the biggest mysteries about introns that would probably be impossible for them to understand fully without their combined expertise.

“It is the best way to do things,” Ares said. “When you find someone who has the same kind of questions in mind but a different set of methods, perspectives, biases, and weird ideas, that gets more exciting. That makes you feel like you can break out and solve a problem like this, which is very complex.”

More information: Manuel Ares et al, Intron lariat spliceosomes convert lariats to true circles: implications for intron transposition, Genes & Development (2024). DOI: 10.1101/gad.351764.124

Provided by University of California – Santa Cruz

Citation: Study discovers cellular activity that hints recycling is in our DNA (2024, May 11) retrieved 10 July 2024 from https://phys.org/news/2024-05-cellular-hints-recycling-dna.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.