Millions of rocks orbit within the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, but only some fly relatively close to Earth.

NASA classifies asteroids that orbit within 30 million miles (50 million kilometers) of Earth as near-Earth objects (NEOs). But within this population of space rocks is a sub-group of particularly worrisome objects that are so large, and orbit so closely to Earth, that they could pose a real threat to our planet if a direct collision were to occur. NASA calls these troublesome rocks “potentially hazardous asteroids” (PHAs), or “potentially hazardous objects” (PHOs).

How many potentially hazardous asteroids are there, and how big a threat do they pose? Here’s everything you should know about the risky space rocks.

What are potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs)?

Potentially hazardous asteroids are NEOs that are larger than 460 feet (140 meters) in diameter and that could come within 4.65 million miles (7.48 million km) of Earth, or roughly 20 times the average distance between Earth and the moon. If an asteroid of this size were to make it through Earth’s atmosphere without burning up, it could cause widespread damage and countless injuries — particularly if it landed in a major city or densely populated area.

Related: Could an asteroid destroy Earth?

How many potentially hazardous asteroids are there in the solar system?

The following chart shows the cumulative number of known Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs) versus time. Totals are shown for NEAs of all sizes, those NEAs larger than ~140m in size, and those larger than ~1km in size. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

As of March 2023, NASA had identified (opens in new tab) around 31,000 NEOs. Of those, about 2,300 are considered potentially hazardous. Many of these objects come from the main asteroid belt, and their orbits shifted as the solar system evolved over millions of years. According to NASA, about half of the known NEOs are larger than 460 feet in diameter, but they do not orbit close enough to Earth to pose a threat.

NASA has calculated the trajectories of all known PHAs and determined that none threaten Earth for at least the next 100 years.

How do NASA and other space agencies monitor PHAs?

This chart illustrates how infrared is used to more accurately determine an asteroid’s size. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Scientists and amateur astronomers search the skies all over the world, looking for pinpricks of light moving relative to the dark curtain of outer space. These observations are generally made with ground-based telescopes like the Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona or the Infrared Telescope Facility atop Hawaii’s Mauna Kea volcano. A satellite called NEOWISE (opens in new tab) monitors the skies from space.

When someone spots an asteroid or a comet, they report it to the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center, which compiles all observations of small bodies, including asteroids and comets, in the solar system. From there, scientists at other observatories can make more measurements to determine an asteroid’s precise orbit and whether it may threaten Earth.

To accurately measure an asteroid’s size, scientists use infrared light, or heat, which is a better indicator of an asteroid’s mass than the amount of light it reflects. Scientists also use radio telescopes to bounce radio waves off of asteroids. By precisely measuring the time it takes for the radio waves to travel to an asteroid and back, scientists can determine its size and shape.

After several observations, scientists can calculate an asteroid’s orbit out to 100 years.

How are we prepared to deal with PHAs?

Movies like “Armageddon” and “Deep Impact” tell us tales of brave astronauts who make the ultimate sacrifice: traveling to space to destroy rogue asteroids hurtling toward Earth. But as usual, real life isn’t so dramatic. Scientists have determined that the best way to defend Earth from an asteroid impact is to use nonhuman methods. By shifting an asteroid’s orbit by a tiny amount, we can cause it to miss Earth entirely.

NASA scientists have studied a few ways to shift an asteroid’s orbital path. One method is called a gravity tractor, in which a spacecraft would orbit an asteroid and nudge its orbit using the effects of gravity. Another method would be to detonate a nuclear explosive near the asteroid (not inside it), to push it off course.

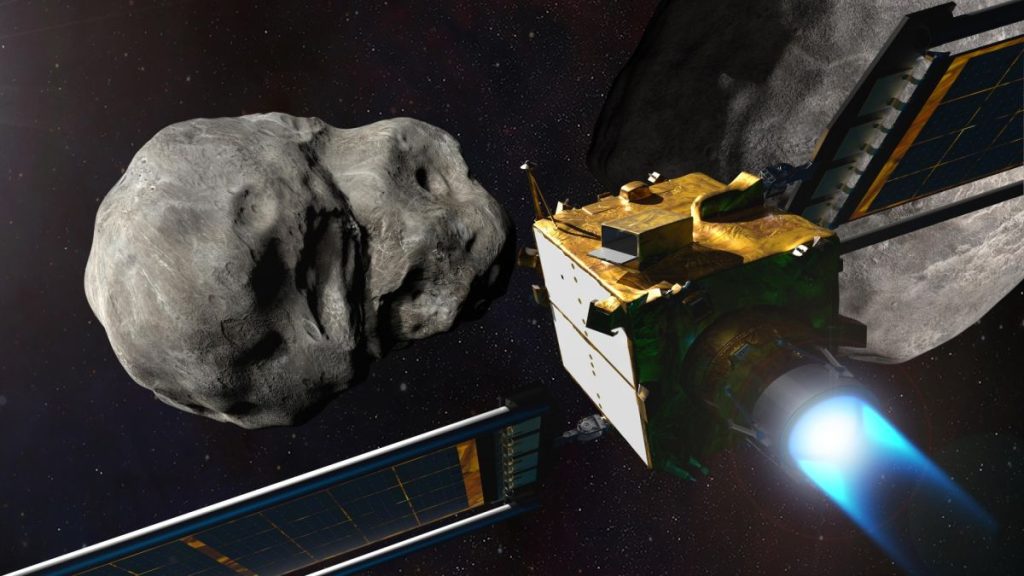

More realistically, NASA scientists propose that a kinetic impactor would be the best and most feasible method of deflecting an asteroid with today’s technology. A kinetic impactor is a spacecraft that would collide with the asteroid on purpose. In September 2022, NASA’s Double-Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission smashed into a small moon of an asteroid at 14,540 mph (23,400 km/h). The collision altered the space rock’s orbit around its host asteroid by 32 minutes, proving that the kinetic impactor method can work.