A new laser-based technique has revealed the intricate details of tattoos on centuries-old mummies in Peru, archaeologists report in a new study. However, not everyone is convinced that the new technique is better than existing methods for analyzing historical tattoos.

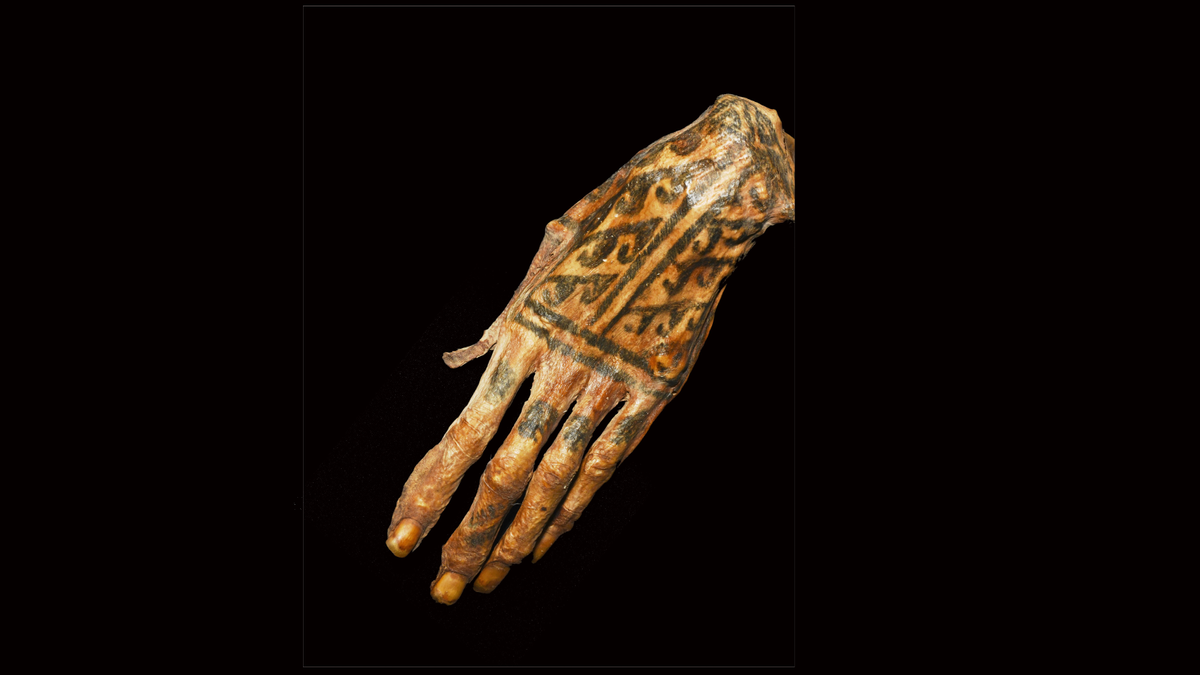

In the study, published Monday (Jan. 13) in the journal PNAS, researchers looked at more than 100 mummified human remains from the Chancay culture, which inhabited Peru from about A.D. 900 to 1533. “Only 3 of these individuals were found to have high-detailed tattoos made up of fine lines only 0.1 – 0.2 mm [0.004 to 0.008 inch] thick, which could only be seen with our new technique,” study co-author Michael Pittman, a paleobiologist at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, told Live Science in an email.

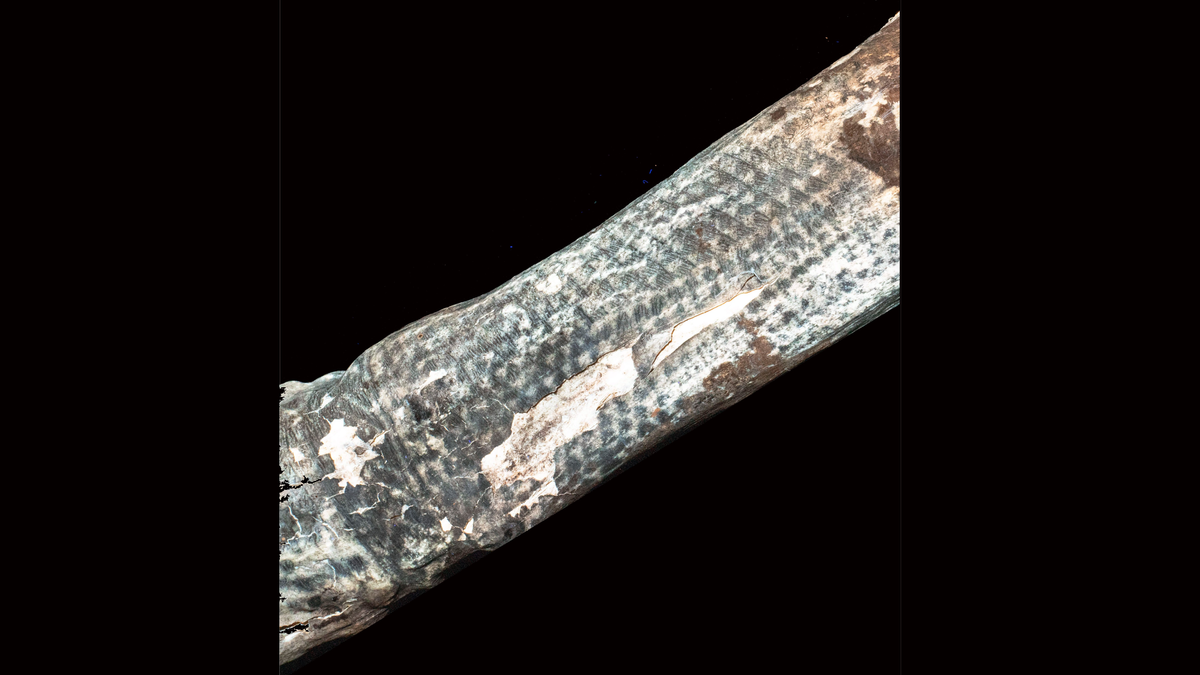

The technique involves laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF), which produces images based on the fluorescence of a sample, thus revealing details that can be missed by simple ultraviolet (UV) light examination. LSF works by making the tattooed skin fluoresce bright white, which causes the carbon-based black tattoo ink to stand out clearly. This almost completely eliminates the issue of tattoos bleeding and fading over time, which can obscure the design, according to the study.

The three highly detailed tattoos the team revealed on the mummified remains were “predominantly geometric patterns featuring triangles, which are also found on other Chancay artistic media like pottery and textiles,” Pittman said, while other Chancay tattoos included vine-like and animal designs.

The Chancay culture, which developed along the central coast of Peru about a millennium ago, is best known for its black-on-white ceramics and textiles, according to Kasia Szremski, an archaeologist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who was not involved in the study. The Chancay people were “kind of like House Frey from ‘Game of Thrones,'” Szremski told Live Science in an email, “in that they were waiting out the Chimu-Inka conflict [circa 1470] until they could see who had the advantage and join the winning side.”

But little is known about the social organization of the Chancay culture, which makes the study interesting and important, according to Szremski. “In many societies, tattoos are used to mark people with special status,” she said, so “by better understanding what Chancay tattoos look like, we can start looking for patterns that may help us identify different types, classes or statuses of people.”

However, Aaron Deter-Wolf, an ancient-tattoo expert at the Tennessee Division of Archaeology who was not involved in the study, is not convinced that the LSF technique is useful. Deter-Wolf told Live Science in an email that the study authors failed to include important details about the LSF technique and did not explain why it is better than currently used techniques, such as high-resolution infrared or multispectral imaging.

Additionally, Deter-Wolf took issue with the authors’ conclusion that two of the tattoos illustrated in their study were created by the puncture method, in which each ink dot was placed by hand. Rather, he noted that the tattoos were created by incising short parallel lines in the skin, with pigments rubbed in from the surface.

Deter-Wolf was “dismayed” by the errors he noted in the paper and suggested that the study “does not make a significant contribution to the current understanding of ancient Andean cultural practices.”

Although the published study does not detail exactly which mummies from the Arturo Ruiz Estrada Archaeological Museum’s collection in Peru were analyzed, Szremski pointed out that there is incredible value in reassessing museum collections using new techniques such as LSF.

“While we still don’t know what these tattoos mean, their intricate nature does tell us that the Chancay had tattoo artists!” Szremski said. “It isn’t something that just anyone could have done.”

LSF imaging “has the potential to reveal similar milestones in human artistic development through the study of other ancient tattoos,” Pittman and colleagues wrote in the study, “including the evolution of tattooing methods.”