Heat waves are happening at the bottom of the ocean, a new study finds.

And these so-called “bottom marine heat waves” can be devastating because they last longer than surface heat waves and affect many key species, such as lobster and cod.

It’s long been known that spikes in surface water temperature can devastate an ocean’s ecosystem. For example, from 2013 to 2016, the surface waters of the Pacific Ocean along the North American coastline warmed up in a phenomenon dubbed “the blob,” which led to the deaths of 1 million seabirds because their main meal source (fish) had been severely impacted.

But something similar is percolating in deeper waters. The team published its findings March 13 in a study in the journal (opens in new tab).

“This is a global phenomenon,” lead author Dillon Amaya (opens in new tab), a research scientist in NOAA’s Physical Science Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, told Live Science. “We’re seeing [bottom] marine heat waves happening around Australia and in places like the Mediterranean and Tasmanian seas. This is not something that’s unique to North America.”

The ocean has absorbed approximately 90% of the excess heat from global warming. This has led to an increase of about 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) over the past 100 years, according to NASA (opens in new tab). This uptick has resulted in a 50% increase in surface marine heat waves in the past decade, the researchers said in a statement (opens in new tab). But scientists had no clear picture of how the ocean depths responded when surface temperatures spiked.

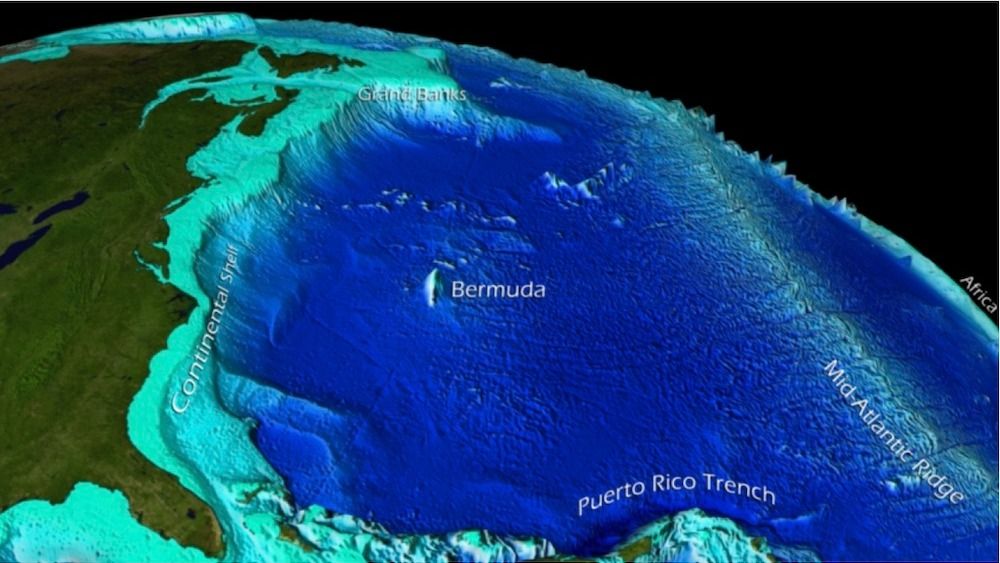

To understand how atmospheric temperature changes were affecting the ocean bottom, scientists used existing measurements to simulate atmospheric conditions and ocean currents to “fill in the blanks” for difficult-to-access seafloor ecosystems. These ecosystems are often populated by lobsters, scallops, flounder, cod, and other commercially fished creatures, according to the statement.

Related: Ocean temperatures have reached a record-breaking high

The researchers discovered that along the continental shelves near North America, bottom marine heat waves lasted longer than similar surges at the surface. They also found that these temperature fluctuations can occur simultaneously at both the surface and the seafloor at the same location and are most prevalent in shallow areas where waters from different levels can intermingle, according to the study.

Warm bottom water temperatures have previously been linked to an increase in invasive lionfish populations and coral bleaching, according to the statement.

Scientists don’t yet have a good enough picture to predict when and where such bottom marine heat waves will occur.

But “we do have some hypotheses about why these things are happening,” Amaya said. “One dynamical driver could be changes in ocean currents. For example, on the U.S. East Coast the coastal system is dominated by the gulf stream, which is a warm water current, and its variability could absolutely change the bottom temperature of the water.”

Another potential factor is upwelling, or the rising of colder, deeper water upward in the water column.

“For example, along the U.S. West Coast there’s a lot of cold, nutrient-rich water that comes from the depths and can wash along the continental shelf, and any changes in the rate of upwelling can be seen as changes in subsurface temperature along the continental shelf.”