This past year, like the rest of the bookish world, I sat enthralled by every update from the trial where the U.S. Department of Justice fought to block Penguin Random House’s acquisition of Simon & Schuster, another member of the Big Five. As I read updates about the trial, I kept getting flashbacks from when I was working for a university press and first heard about the negotiations for the Penguin–Random House merger back in 2012. But this time, I became distracted by something else coming out of the trial: a disdain that big publishing executives had for smaller presses.

I remember when I first read the article by Margot Atwell, Executive Director and Publisher of Feminist Press, discussing how witnesses in the trial kept referring to indie presses as “farm teams.” Atwell wrote, “Referring to independent book publishers as ‘farm teams’ implies that they are small-time, amateur, and lower-quality than the massive corporate publishers that dominate the publishing landscape. It also implies that indie presses exist solely to develop raw talent to the standards of Big 4 or 5 publishers — and for their benefit.”

Now don’t get me wrong; I love books from big presses. Some of my favorite books come from imprints like Knopf, Scribner, and Little, Brown. But big publishing isn’t the only place where excellent books are made. Smaller presses provide a place for a lot of books big publishing doesn’t want to take a risk on, like books in translation, experimental works, and books by authors from marginalized identities. Smaller presses know their communities and invest in the literature that they specialize in, making a way for a wider range of books to be published.

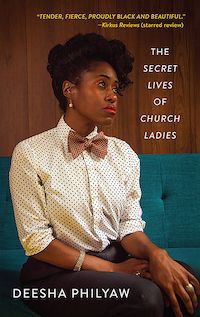

As a bookish person in the South, far away from the hustle and bustle of the publishing houses based in New York City, I work with a lot of wonderful university and indie presses that publish incredible books featuring a diverse range of titles across the board. One of my favorite books of the last few years, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies by Deesha Philyaw, came out from West Virginia University Press (WVU Press). Philyaw’s book was a finalist for the National Book Award, and Tessa Thompson and HBO Max will produce a series based on the short story collection.

When I talked to Derek Krissoff, the Director of WVU Press, on my podcast Read Appalachia, he described his perspective on WVU Press’s approach as a “Community Publisher” and how they work with its community to tell stories from West Virginia and broader Appalachia.

Book Deals Newsletter

Sign up for our Book Deals newsletter and get up to 80% off books you actually want to read.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox.

By signing up you agree to our terms of use

“We’re responsive to the communities where we are rooted,” Krissoff said. “We have perspectives that are grounded in the places where we are. We try to make a path for people to get into publishing work from these places outside of big cities.”

Here in my hometown of Spartanburg, South Carolina, Hub City Press, a nonprofit indie press, puts out some of my favorite indie press books, like The Prettiest Star by Carter Sickels and Whiskey & Ribbons by Leesa Cross-Smith. Many of these stories focus on the landscape of the American South, deeply connecting storytelling with an intense sense of place. Their books push back against stereotypes that much of the rest of the country holds about the South. Much of their list includes Southern poets like Alabama’s Poet Laureate, Ashley M. Jones, and MacArthur Fellow J. Drew Lanham.

When I talked to Hub City Press Director Meg Reid on Read Appalachia, she described the importance of thinking about where our books come from and how our dollars might better support supporting smaller publishing communities:

“People need to decentralize in their own minds where their books come from. They need to have better education about publishing systems and then buy books and seek out books from more publishers…It’s just a real shame that people are reading just so much that comes through the same main office, you know, is being processed through that same publisher or at least that same conglomerate or couple conglomerates. Cause when you look at independent presses and smaller presses, they are so much more local. They are so much more supportive of the communities that they are in.”

University and independent presses provide communities a way for our stories to be told — cultivated, edited, published, and marketed — by people who understand the nuances of our culture and perspective of the world. Without these presses investing in our communities, literature would lose much of its diversity as major publishers shy away from taking a chance on these authors.

Whether they’re from a big corporation that publishes thousands of titles a year or from a small press that publishes eight titles a year, great books come from so many different kinds of publishing houses. So it’s a mistake to view small presses as just a place to test out titles to see if they will “make it” in the big league. Smaller presses are unique extensions of their communities, committed to telling their authors’ stories.

I think Meg Reid said it best: “Imagine the good that can happen if there are more publishers representing more people and publishing books that are more honest to people’s lived experiences because they are on the ground living with them.”

Want to read some work from small press? Try these must-read story collections and anthologies, some of our favorite indie nonfiction from 2022, and this roundup of small press books from 2020.