Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson by Rebecca Boggs Roberts

The White House has been home to many deceitful acts. One of the lesser-known frauds occurred between 1919 and 1920, after President Woodrow Wilson suffered a stroke during the peace negotiations following World War I. In the course of several months of diplomacy in Europe — largely at Versailles — Wilson’s condition deteriorated. His wife, Edith, and personal physician would spend the remaining year of the 63-year-old president’s term covering up his physical and cognitive decline.

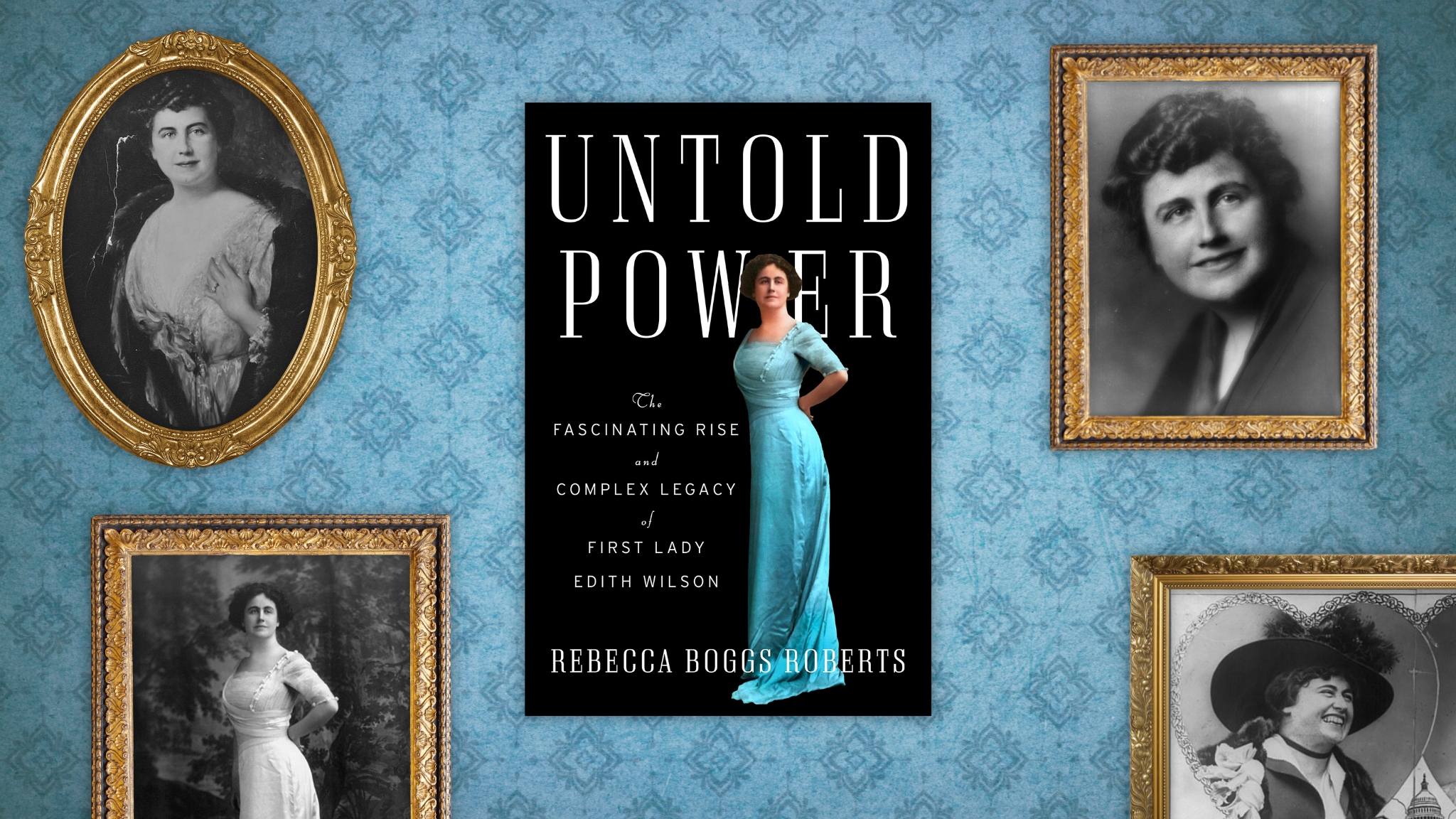

In her new biography of First Lady Edith Bolling Wilson, journalist Rebecca Boggs Roberts tackles that subterfuge. Untold Power: The Fascinating Rise and Complex Legacy of First Lady Edith Wilson (Viking) is not the first book to explore Edith’s bold assumption of presidential duties. However, Roberts argues, Edith has long been typecast: a poser, an opportunist, a master manipulator.

“It’s time for a fuller picture of this remarkable woman,” writes Roberts, whose work benefited from access to unpublished chapters of Edith Wilson’s 1939 memoir.

Sixteen years younger than the president, Edith Bolling was an unreconstructed Southerner who grew up in rural Wytheville, Virginia. Buried in her pedigree were Native Americans and aristocratic Royalists, but that legacy had dimmed by the time she was born in 1872. Leaving Appalachia, Edith hoped to never look back.

Edith landed in Washington, D.C., still a very Southern city when she arrived in 1890. Living with her sister and brother-in-law, she soon became aware of her middling social status. Yet the tall, curvaceous eighteen-year old with violet-gray eyes drew many admirers, including Norman Galt, owner of the jewelry store Galt & Bros. The Galt family was “in trade,” but the prosperous business had been patronized by Washington’s elite, known as “cave dwellers,” for nearly a century and conferred prestige on the Galt family. In 1896, Edith agreed to marry Norman.

Tragically, a baby boy born to the Galts in 1903 would live just three days. One year later, Edith became the first woman in Washington to receive a driver’s license and began to scoot happily around town in her electric car. She had been told that she could not have more children.

It is evident that Norman was not the love of Edith’s life but the couple were compatible and lived well. His death in 1908 shocked family and friends. Now fully independent, Edith spent much of the next few years traveling extensively in Europe.

Apparently she felt lonely but maintained a small social circle. The city’s political whirl passed her by. She paid little attention to the 1912 presidential election, which swept Wilson into office, nor the illness of his wife, Ellen, who died of kidney disease in 1914. In contrast, the president’s longing for a female companion became palpable.

It was Wilson’s personal physician, Dr. Cary Grayson, who contrived an introduction between Edith Galt and the president. Grayson urged Edith to befriend Wilson’s 40-year old cousin, Helen Bones, and the women hit it off. Next, the doctor and cousin arranged for Edith and Woodrow to meet at the White House, seemingly by accident. After the four enjoyed tea, the president invited Edith to dinner.

Throughout much of 1915, Woodrow courted Edith assiduously. He soon learned that Edith was aroused not only by florid love letters and kisses but detailed discussions of affairs of state. Thus the president developed the habit of sharing top-secret information with her.

They married in December 1915. As first lady, Edith quietly made changes to longstanding social etiquette and, Roberts notes dryly, banished Wilson’s twin beds and replaced them with the Lincoln Bed. She stood with her husband in opposition to women’s suffrage. Together they anticipated his 1916 loss to the Republican candidate, Charles Evans Hughes. But Wilson won.

The United States entered World War I in April 1917. Here, the author’s account of the relationship between the president and the first lady opens into an epic drama of their collaboration and deep love for each other.

While President Wilson arrived triumphantly in Paris to participate in negotiations pursuant to the Treaty of Versailles, his stamina and intellect declined noticeably during the seven months that the Wilsons spent in Europe. Roberts writes that a stroke is the likeliest explanation.

Back in the United States, Edith’s fervent desire to protect the president’s legacy led her (and Grayson) to devise elaborate deceptions that gave the impression of good health. They covered up yet another debilitating stroke.

“Her entire goal, from the beginning, was to protect her husband at any cost,” writes Roberts. “So she lied when she could and told the truth when she had to.” This intriguing biography will disturb and surprise readers.

Q&A With Rebecca Boggs Roberts

Q: In your introduction, you describe how conflicting characterizations of Edith Wilson have led to the general impression of her as a “shape-shifter.” Do you think that most modern First Ladies have encountered this problem or was Wilson’s situation especially unpleasant?

A: I think all First Ladies have to handle public characterizations of themselves that are not necessarily fair or accurate. Some of it is just the nature of a public role — each First Lady presents a public persona, which can never be a full picture of a real, complex human. I think Edith exacerbated the problem herself, by choosing the public persona of exceptionally devoted wife, then curating and protecting that image fiercely till the day she died. As more information came to light about the true extent of her role in the executive branch, the contrast between public image and private action became especially stark.

Q: In light of your extensive work on the history of American women’s struggle to get the vote, how did you react to the Wilsons’ opposition to women’s suffrage?

A: A colleague recently accused me of “sleeping with the enemy” for amplifying the story of anti-suffrage Edith. She was kidding, I think. Woodrow’s opposition is easy to understand: it was garden-variety sexism mixed with political math. He wanted southern votes, so he supported a states-rights approach to suffrage as long as he could. When more and more states enfranchised women, he realized the Democratic party would lose a bunch of new voters, and he changed his tune to federal support. Edith’s anti-suffrage stance is much harder for me to comprehend. She was an independent, business-owning, car-driving, sophisticated widow of means. Why wouldn’t she want to exercise her full rights as a citizen? She found the suffragists’ aggressive tactics distasteful, but it was more than that. On some fundamental level, she just wasn’t sure participating in politics was an appropriately feminine thing to do. Which was deeply ironic, given how thoroughly she controlled the executive branch after Woodrow’s stroke. See “contrast between public persona and private action,” above.

Q: Woodrow Wilson’s first wife, Ellen, was demure, artistic and essentially Victorian. Why do you think that the president subsequently fell so hard for brainy, vivacious Edith?

A: Ellen was perfectly suited for the world of academia she thought she was getting when she married a professor. And although she did have good political instincts (during the 1910 New Jersey gubernatorial race, Joe Tumulty claimed she was a better politician than her husband), Ellen was shy and awkward in the First Lady limelight. Edith, by contrast, was stylish and clever and at ease everywhere she went. She exuded a glamour and confidence Ellen could never match, and was great at the public ceremony required of First Ladies. I am not saying Woodrow was cynical enough to choose a wife based on his professional needs — one glance at his love letters proves the depth and sincerity of his feelings for both women. But he was at different places in his life when married them. Young Edith would have terrified the shy PhD student who fell for demure Ellen. By the time he met Edith, he had grown enormously in his own confidence and self-knowledge.

Q: Were security procedures surrounding presidential communications less stringent in 1919-1920 than they are today? Do you think Edith Wilson actually realized the extent to which she was violating protocol by operating so secretively?

A: Edith definitely knew what she was doing was irregular — that’s why she was so secretive. She just didn’t care. She had one goal: protect Woodrow for as long as she had to. If she had to violate protocol, lie to the Congress, press & public and bar anyone from visiting the White House, then so be it.

Q: Can you tell us what you’re researching now? Do any other First Ladies call for their stories to be told?

A: I haven’t chosen my next subject yet, mainly because there are SO MANY women whose stories have been forgotten, warped or reduced to boring stock characters. First Lady Rose Cleveland. Temperance activist Carrie Nation. Civil War detective Kate Warne. I want to write about them all! But in addition to good primary sources and other research material, you really need to have affection for your subject, even if you don’t think she’s perfect. I haven’t decided who I like enough yet to spend the next few years with. Stay tuned …

Publish Date: March 7, 2023

Genre: Biography

Author: Rebecca Boggs Roberts

Page Count: 320 pages

Publisher: Viking

ISBN: 9780593489994