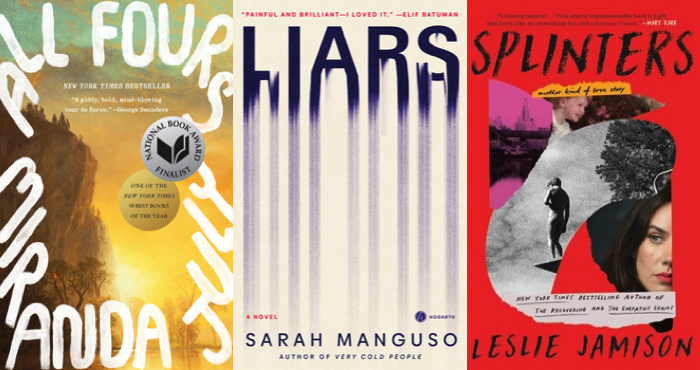

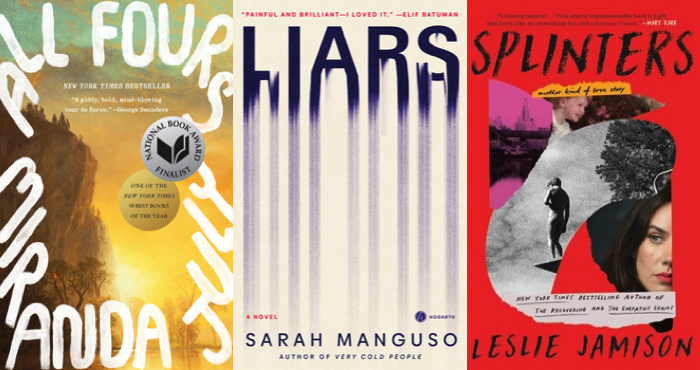

In Book Forum, Hermione Hoby considers the stuffed shelf that is the contemporary novel/memoir of divorce. And while she doesn’t inspect All Fours directly, much, if not all, of her thinking applies there. She sets up the inquiry I think with welcome clarity:

Why, when divorce in the US and the UK is at last widespread, destigmatized, and more legally unimpeded than ever, should it have this literary salience? The question becomes more puzzling when one notes that the books in question are overwhelmingly authored by a certain kind of woman: she is white, straight (or at least separated from a man), cisgender, middle class, and in her thirties or forties—a professional writer before her divorce, she remains one afterward. She belongs, in other words, to one of the demographics whose members are least likely to be socially punished or economically penalized for getting out of a marriage. I’m friendly with some of these women—a friendliness based, in large part, on admiration for their work. But what puzzles me is that divorce has acquired increasing literary significance to the very degree that marriage has forfeited social meaning.

The thing I might quibble with here is actually the prevalence and popularity of these books might suggest a lessening literary significance, which I consider distinct from popularity. That these authors want to write them, and that there seems to be a decent readership for them, doesn’t necessarily mean that they are significant. Rather, that the divorce narrative, with its regular beast of early happiness, growing dissatisfaction, decisive moment of change, bumpy aftermath, and (usually) some sort of eventual recovery, is now common enough to be its own mini-genre. And like the happy ending of a romance novel, the experience of reading through the trials and tribulations of a divorce story are in their own way satisfying. The lack of introspection Hoby identifies in these books then is, as they say, a feature, not a bug.