The US government could run out of money as early as next week if lawmakers in Washington DC fail to reach an agreement to increase the federal debt limit. If the worst happens, economists warn, it would be the first time in history that the government has defaulted on paying its loans, and it could throw the country — and possibly the world — into financial turmoil. Also hanging in the balance, as politicians haggle over government spending, is a decade of funding for research and innovation, and many science advocates fear that budget cuts are inevitable.

“I’ve come to terms with the reality that whatever the agreement, there will be a decrease in discretionary funding” next year, says Joanne Carney, chief government-relations officer for the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington DC. That, she adds, means there will be less funding for research and development (R&D). Discretionary funding is the money that the US Congress divides up, during the annual appropriations process, among federal science and other agencies and programmes.

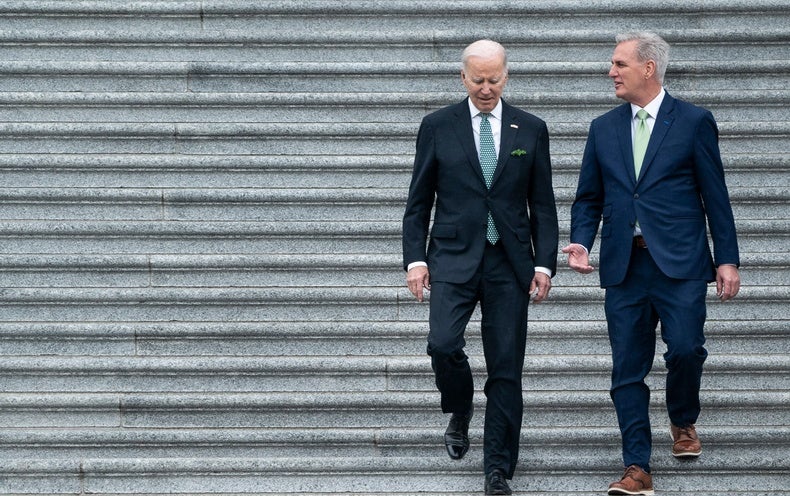

The impasse between President Joe Biden, a Democrat, and Republicans hinges on the ‘debt ceiling’, a congressionally imposed limit on how much money the US government can raise by issuing bonds and using other financial instruments to cover its spending (the United States currently spends more money than it raises in taxes). As it stands, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has declared 1 June a “hard deadline”, saying that the nation could default on its debt payments if the ceiling is not raised by then. Federal agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) could also be left unable to make payments, such as those covering research grants and salaries for federal scientists.

Republicans, who control the US House of Representatives, are using the approaching deadline as leverage to try to push through spending cuts. In the House, they have passed a bill proposing massive budget cuts that could limit government spending across the board over the coming decade, in exchange for raising the debt ceiling. So far, the Biden administration and the Democrats have held off on making an agreement. Some argue that Biden should use his executive authority to head off the crisis by unilaterally extending the government’s ability to borrow money.

No one knows precisely how the political brinkmanship will play out, but history suggests that the impacts — including those for US science — could be felt for years to come.

Spending caps

For many in Washington, the current showdown feels like a replay of events that occurred during former president Barack Obama’s first term in 2011, when Republicans used a looming debt-ceiling deadline to try to limit federal spending for a period of nearly a decade. “Quite frankly, this movie wasn’t great the first time, and I think the sequel is going to be a lot worse,” says Jennifer Zeitzer, who leads the public-affairs office at the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB), based in Rockville, Maryland.

Although in the years that followed Congress approved funding that exceeded the spending caps laid out in 2011 a number of times, the debt-ceiling agreement took its toll. Funding for R&D was reduced by an estimated US$240 billion over the next nine years, according to Matt Hourihan, who analyses science budgets for the Federation of American Scientists, an advocacy group based in Washington DC. That’s equivalent to the amount of money needed to support the NIH — the largest public biomedical funder in the world — for five years at its current budget levels.

“That is a pretty sizeable spending shortfall,” Hourihan says. It would have been worse had lawmakers stuck to their original promises.

Round two

The spending cuts now being sought by Republicans are even more severe: the bill passed last month would reduce discretionary spending by more than $3.5 trillion over the coming decade. Assuming Congress was to allocate those cuts evenly across agencies and programmes, Hourihan says overall federal investments in science would be reduced by an estimated $442 billion through 2033, a decline of 19% compared with a baseline scenario in which science investments increase with inflation. And cuts for science agencies such as the NIH and the National Science Foundation (NSF), which funds about one-quarter of the federally funded basic academic research in the United States, could be much deeper if spending on defence R&D is excluded from the caps, as some lawmakers have proposed doing.

The push to curb spending comes less than a year after Congress enacted legislation authorizing a massive increase in federal spending on science and innovation, including a doubling of the NSF’s budget through 2027. That legislation, called the CHIPS and Science Act, drew bipartisan support owing to rising concern about economic and scientific competition with China. “We’re still in a place where we can’t seem to back up our rhetoric with the kind of investments that we hoped for,” Hourihan says.

Meanwhile, lawmakers are still working through the usual appropriations process for the fiscal year 2024, with Republicans seeking to reduce federal spending to levels enacted in 2022. If those cuts were spread evenly across all discretionary programmes, federal science investments would drop by 20–22% in 2024, according to FASEB.

One possibility is that Republicans and Biden reach a deal to increase the debt ceiling without resolving questions about 2024 spending levels. In such a scenario, the fallback position for both parties later this year could be a continuing resolution that holds 2024 funding flat at 2023 levels, Zeitzer says.

“That’s still better than direct cuts, but it’s not great for the research enterprise,” Zeitzer says. “We’re holding our breath.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on May 22, 2023.