It’s been a perfect storm. Anecdotal reports of animals dying have unnerved people. Residents have reported feeling sick even as the US Environmental Protection Agency—which infamously and errantly declared the air quality in Manhattan following the September 11, 2001, attacks safe—said that it hadn’t detected chemicals that meet “any levels of concern.” A reporter was arrested at a press conference, sparking theories that there could be an active cover-up underway. Chinese media began covering the derailment, and the topic trended on China’s Weibo social app as extended coverage of China’s spy balloon saturated news coverage in the US. Some have suggested the US media’s massive focus on the Chinese spy balloon was a calculated misdirect, pulling attention away from the train derailment.

“This is kind of the ultimate event for driving conspiracy theories and various anti-government and anti-media sentiment,” says Meghan Conroy, a US research fellow with the Atlantic Council, an international affairs think tank who has followed social media coverage of the derailment. “There’s a lack of clarity about what’s happening on the ground in Ohio.”

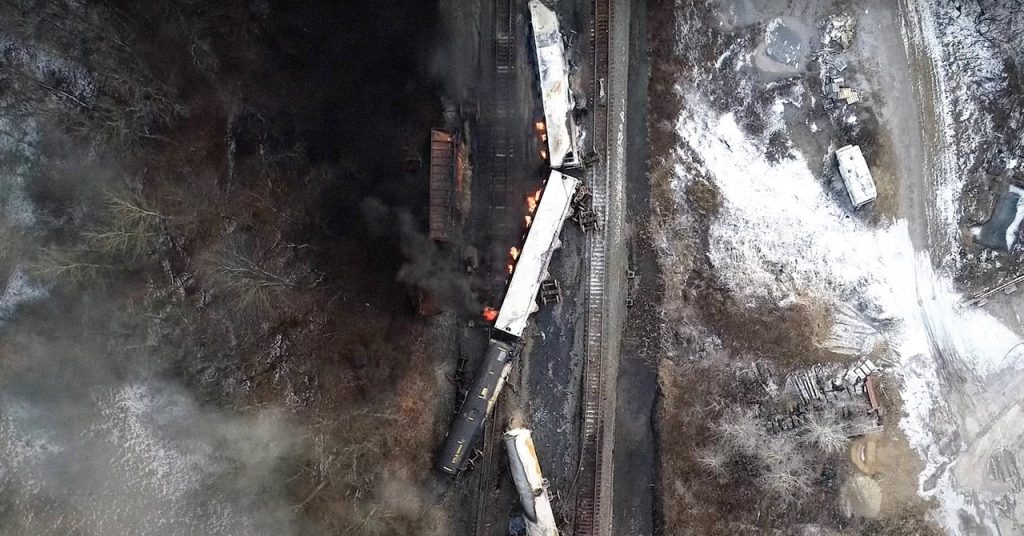

While the EPA is monitoring air and water quality in East Palestine, some of the long-term health and environmental effects of the chemical burn and spill are unknown. (In fact, it wasn’t until Sunday—nine days after the derailment—that the EPA provided a full list of chemicals aboard the train, which was operated by Norfolk Southern Railway.) Investigations are underway, and the results aren’t immediately available. The situation has created what is called a data void, says Conroy. Unsatisfied with answers from the media and government, people look elsewhere for answers, and some step in to fill the gaps.

It’s typically people on the political right who are distrustful of the media and government who drive these types of conspiracy theories, but the train derailment is unique in that it has enthralled both sides. “What we are seeing here are folks across the ideological spectrum taking guesses about why we’re not getting much information,” Conroy says.

People have insisted there’s a media blackout at play. Some, including US representative Ilhan Omar, a Minnesota Democrat, have taken to social media to slam the national news for failing to cover the disaster, despite several stories from The New York Times, CNN, and NPR all reporting on the derailment in the immediate aftermath.

Then there’s the decision to burn off one of the chemicals—vinyl chloride, a carcinogen—to avoid an explosion, which Ohio governor Mike DeWine described as one of “two bad options.” The science around the chemical burn is foreign to many, and alarming. But experts say the outraged response has gone too far. Several government agencies have reported that they have not found dangerous levels of chemicals in the air and water, yet doubt continues to make its way through social media.

“Some of the social media posts are not accurate or, at minimum, overblown,” Daniel Westervelt, a research professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory who focuses on ocean and climate physics, says, like posts that have compared the toxic spill to the Chernobyl disaster. After reviewing Drombosky’s viral video, Westervelt said a lot remains unknown about the derailment and suggested taking “certain claims with a grain of salt” when asked if the information presented was accurate.