“My own solution for the problem of Venice is to let her sink,” wrote British author and onetime Venice resident Jan Morris with casual mercilessness in a 1971 essay for The Architectural Review . She reiterated the point in The New York Times four years later, hammering home her point with conviction and relish: “Let her sink.”

And yet Morris predicted that this would never be Venice’s fate, because “the world would not allow it.” That may be true. What she wasn’t right about was the time frame of the impending tragedy. She thought it would be a long time coming—“One cannot hang around for the apocalypse”—but likely didn’t envisage that only 50 years later, scientists would be able to predict that, in a worst-case scenario, Venice could be underwater by 2100. Prepare the horses; the apocalypse is here. You don’t prepare for the end of the world by battening down the hatches and staying put— you need to adapt.

“One thing we’re trying to explore in heritage practice is going beyond the impulse to save everything all the time,” says UK-based cultural geography professor Caitlin DeSilvey. In her 2017 book Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving, DeSilvey wrote about letting landscapes and landmarks transform, buffeted by the wind or eroded by waves, rather than forcing them to remain in the state in which we inherited them. “The heritage sector has a bit of a block, because when you talk about managing that kind of change, and you talk about ruination, that’s perceived to be a failure,” she adds.

But as loss and destruction of global heritage sites due to climate change becomes more commonplace, we need to change the way we think about that loss and redefine our notion of failure. Our values must shift along with our changing climate. As researchers Erin Seekamp and Eugene Jo put it in a 2020 paper, we need a “transition of values from what has been known to what can become, overcoming the tendency for continual maintenance and last-ditch efforts to prolong the inevitable.”

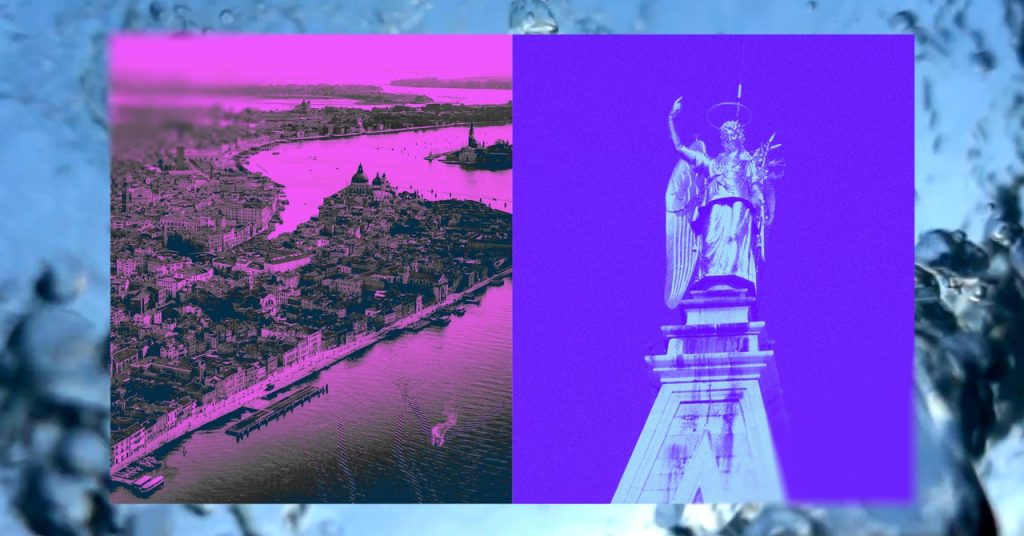

The situation has changed since Morris wrote about Venice, looking out from her perch on the Punta della Dogana. If Morris described the city as a problem in the ’70s, it is now a disaster, swallowed whole by both the rise of water and the rise of tourism.

Though it is well documented that Venice is sinking, its new MOSE flood barriers do an excellent job of protecting it. In November 2022, they saved Venice from its biggest tide in 50 years, which would have devastated the city. But the system was built after years of delays, a corruption scandal, and a price tag of €6.2 billion ($6.9 billion). It is set to cost a further €200,000 each time the barriers are raised, and it will need to be raised ever more frequently. Seekamp and Jo argue that preserving all World Heritage sites and their current values “in perpetuity” is “fiscally impossible.” In Venice’s case, that money could be used instead to relocate the city’s residents, and if its urban heritage is going to be lost or irrevocably changed, we could switch our focus to the protection of its natural heritage, as the lagoon is one of the most important coastal ecosystems in the whole Mediterranean basin.