To stay cool in searing temperatures, the prickly echidna, an egg-laying mammal that lives Down Under, employs a somewhat unusual trick: It blows snot bubbles to keep its nose wet, a new study finds.

“Early lab studies suggested that echidnas can’t survive in temperatures hotter than 35 degrees [Celsius, or 95 degrees Fahrenheit],” said study first author Christine Cooper (opens in new tab), a researcher in the School of Molecular and Life Sciences at Curtin University in Australia. But short-beaked echidnas (Tachyglossus aculeatus) are found all over Australia in places that regularly exceed this threshold, which implies that the spiny monotreme must have some way to beat the heat. The mystery, according to Cooper, was how.

Warm-blooded, or endothermic, animals have several ways to stay cool when the air around them is hotter than their body temperature. One option is to come out only at night and to sleep in burrows or in hollow logs during the hot daytime. But a 2016 study (opens in new tab) suggested that the logs echidnas make their beds in can reach 104 F (40 C) in the summer — far hotter weather than researchers assumed these mammals could survive — so that couldn’t be how echidnas beat the heat.

The second option is evaporation. Most mammals accomplish this by sweating, and those that can’t, like the kangaroo, lick their arms or legs in an effort to evaporate excess body heat. But echidnas neither sweat nor lick themselves. Option three is to pant to stay cool (much like dogs do), but echidnas don’t do that, either.

It was a mystery, but the solution was right under the echidna’s nose, according to the study, published Jan. 18 in the journal Biology Letters (opens in new tab).

Related: Scientists unravel mystery of echidnas’ bizarre 4-headed penis

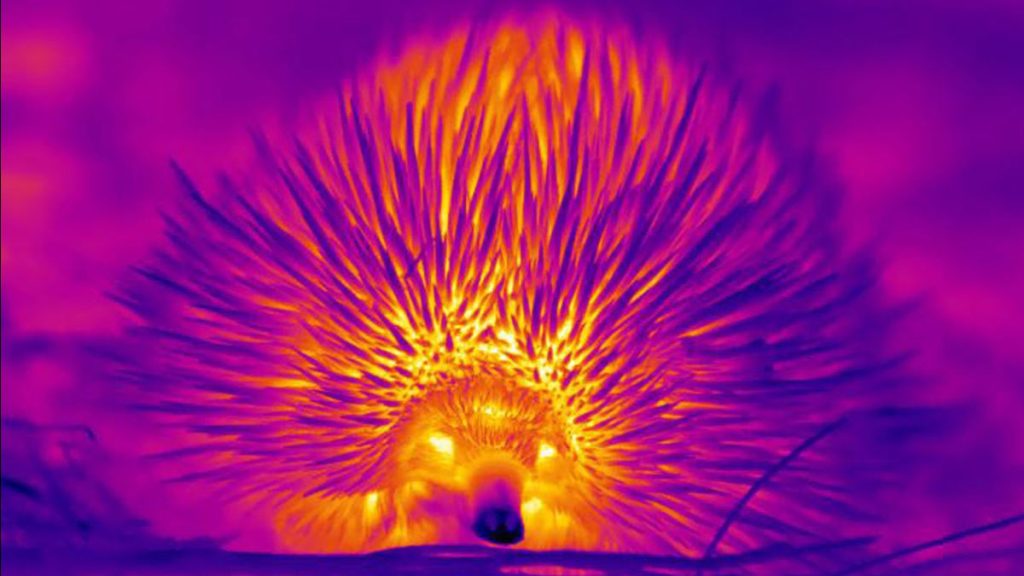

How do prickly echidnas stay cool in the Australian heat? Probably by blowing snot bubbles to keep their noses at a lower temperature, as this heat map shows. (Image credit: Christine Cooper)

The first clue came when Cooper’s doctoral student was studying echidna metabolisms in the lab. The student was measuring the echidnas’ breathing and water loss rates at various temperatures and humidity levels.

“We noticed that our animals would blow bubbles from their nose when we exposed them to higher temperatures,” Cooper told Live Science. “We hypothesized that perhaps this was a cooling mechanism.”

The idea had some promise. The echidna’s beak contains a large “blood sinus,” or a reservoir of blood that pools near the surface. A burst bubble that leaves a coating of mucus could, theoretically, absorb heat from blood and evaporate, thereby keeping the echidna cool. It was an intriguing idea that Cooper decided to test in the field.

This heat map features how booger bubbles keep echidnas’ noses cool in hot Australian weather. (Image credit: Christine Cooper)

Cooper’s study site, about 100 miles (170 kilometers) southeast of Perth, was the ideal spot to observe echidnas in the wild. Cooper and her students have been visiting the site for 20 years, but this time, she brought high-resolution thermal cameras capable of measuring various temperatures across the echidnas’ bodies along with ambient air temperatures.

After recording foraging echidnas throughout a range of seasonal temperatures, Cooper found that whenever temperatures exceeded those of an echidna’s body, its beak would stay cool in the thermal image. In fact, the beak appeared to be the coolest part of the animal’s body, suggesting substantial heat loss from that location.

In addition to keeping echidnas cool, snotty noses can ensure the animals are fed. “The primary reason they keep their noses moist is electroreception,” Cooper explained. Echidnas feed on ants and termites, which they find underground by detecting electrical impulses given off by the muscle contractions of their prey. For their nasal electroreceptors to work, they have to be moist. “But we think that they enhance that when it gets hot,” Cooper said, “so its other role is thermoregulatory.”

Cooper emphasized that echidnas have different behaviors related to temperature regulation throughout the year. They are more nocturnal in the summer and more active during the day in the winter. These strategies likely help the critter deal with extreme temperatures. “I think it gives them more opportunity to expand their foraging,” Cooper said, “and it protects them if they can’t find shelter that’s cool.”

“This paper is a really nice demonstration that it is possible to make quite sophisticated measurements on undisturbed animals in their natural environment,” Stewart Nicol (opens in new tab), an associate professor of biology at the University of Tasmania who studies monotremes, told Live Science in an email. “What is not yet clear is exactly how much cooling this provides for the echidna. Following this up would be an interesting problem.”

That is exactly what Cooper intends to do. “The next step is to model the actual heat loss through these evaporative windows,” she said. This research should reveal clues about echidnas’ ability to forage in extreme heat and help researchers predict how echidnas might cope with increasing average temperatures.