Picture an aircraft streaking across the sky at hundreds of miles per hour, unleashing millions of laser pulses into a dense tropical forest. The objective: map thousands of square miles, including the ground beneath the canopy, in fine detail within a matter of days.

Once the stuff of science fiction, aerial lidar — light detection and ranging — is transforming how archaeologists map sites. Some have hailed this mapping technique as a revolutionary survey method.

The darker side of lidar

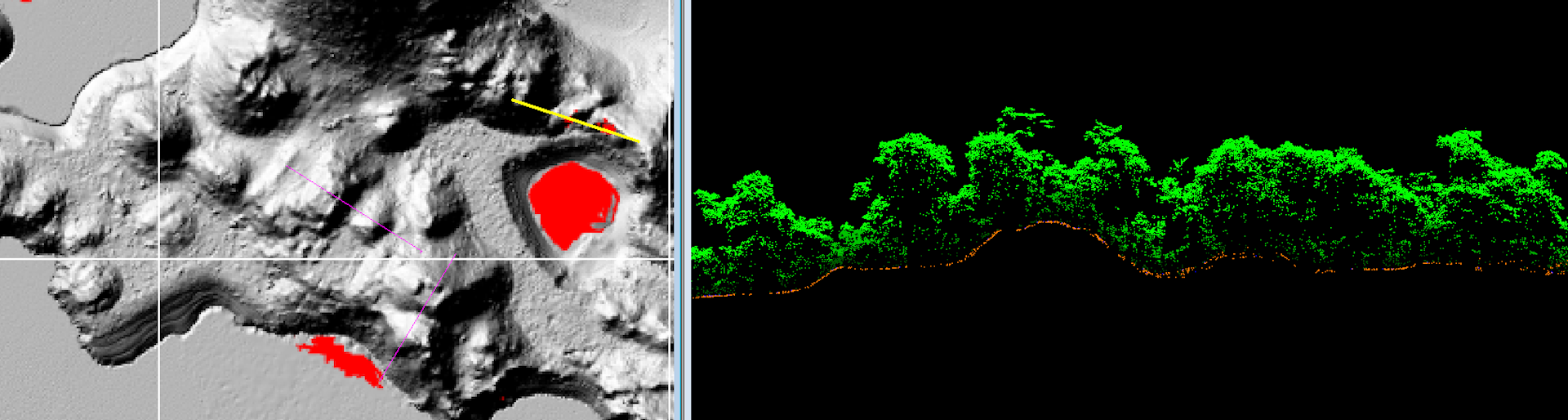

Lidar is a remote sensing technology that uses light to measure distance. Aerial systems work by firing millions of laser pulses per second from an aircraft in motion. For archaeologists, the goal is for enough of those pulses to slip through gaps in the forest canopy, bounce off the ground and return to the laser source with enough energy to measure how far they traveled. Researchers can then use computer programs to analyze the data and create images of the Earth’s surface.

The power of this mapping technology has led to a global flurry of research, with some people even calling for the laser mapping of the entire landmass of Earth. Yet, in all the excitement and media buzz, there are important ethical issues that have gone largely unaddressed.

To rapidly map regions in fine detail, researchers need national but not necessarily local permission to carry out an aerial scan. It’s similar to how Google can map your home without your consent.

In archaeology, a point of debate is whether it is acceptable to collect data remotely when researchers are denied access on the ground. War zones are extreme cases, but there are many other reasons researchers might be restricted from setting foot in a particular location.

For example, many Native North Americans do not trust or want archaeologists to study their ancestral remains. The same is true for many Indigenous groups across the globe. In these cases, an aerial laser scan without local or descendant consent becomes a form of surveillance, enabling outsiders to extract artifacts and appropriate other resources, including knowledge about ancestral remains. These harms are not new; Indigenous peoples have long lived with their consequences.

A highly publicized case in Honduras illustrates just how fraught lidar technology can be.

La Mosquitia controversy

In 2015, journalist Douglas Preston sparked a media frenzy with his National Geographic report on archaeological work in Honduras’s La Mosquitia region. Joining a research team that used aerial lidar, he claimed the investigators had discovered a “lost city,” widely referred to in Honduras as Ciudad Blanca, or the White City. Preston described the newly mapped settlement and the surrounding area as “remote and uninhabited … scarcely studied and virtually unknown.”

While Preston’s statements could be dismissed as another swashbuckling adventure story meant to popularize archaeology, many pointed out the more troubling effects.

Miskitu peoples have long lived in La Mosquitia and have always known about the archaeological sites within their ancestral homelands. In what some call “Christopher Columbus syndrome,” such narratives of discovery erase Indigenous presence, knowledge and agency while enabling dispossession.

The media hype led to an expedition that included Juan Orlando Hernández, then-president of Honduras, pardoned of drug trafficking by U.S. President Donald Trump in 2025. Expedition members removed artifacts from La Mosquitia without consulting or obtaining consent from Indigenous groups living in the region.

In response, MASTA (Mosquitia Asla Takanka— Unity of La Moskitia), an organization run by Moskitu peoples, issued the following statement:

“We [MASTA] demand the application of international agreements/documents related to the prior, free, and informed consultation process in the Muskitia, in order to formalize the protection and conservation model proposed by the Indigenous People.” (translation by author)

Their demands, however, seem to have been largely ignored.

The La Mosquitia controversy is one example from a global struggle. Colonialism has changed somewhat in appearance, but it did not end — and Indigenous peoples have been fighting back for generations. Today, calls for consent and collaboration in research on Indigenous lands and heritage are growing louder, backed by frameworks such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the International Labour Organization’s Convention 169.

A collaborative way forward

Despite the dilemmas raised by aerial lidar mapping, I contend it’s possible to use this technology in a way that promotes Indigenous agency, autonomy and well-being. As part of the Mensabak Archaeological Project, I have partnered with the Hach Winik people, referred to by outsiders as Lacandon Maya, who live in Puerto Bello Metzabok, Chiapas, Mexico, to conduct archaeological research.

Metzabok is part of a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, where research often requires multiple federal permissions. Locals protect what, from a Hach Winik perspective, is not an objectified nature but a living, conscious forest. This land is communally owned by the Hack Winik under agreements made with the Mexican federal government.

Building on the Mensabak Archaeological Project’s collaborative methodology, I developed and implemented a culturally sensitive process of informed consent prior to conducting an aerial laser scan.

In 2018, I spoke via Whatsapp with the Metzabok community leader, called the Comisario, to discuss potential research, including the possibility of an aerial lidar survey. We agreed to meet in person, and after our initial discussion, the Comisario convened an “asamblea” — the public forum where community members formally deliberate matters that affect them.

At the asamblea, Mensabak Archaeological Project founder Joel Palka and I presented past and proposed research. Local colleagues encouraged the use of engaging images and helped us explain concepts in a mix of Spanish and Hach T’an, the Hach Winik language. Because Palka is fluent in Hach T’an and Spanish, he could participate in all the discussions.

Critically, we made sure to discuss the potential benefits and risks of any proposed investigation, including an aerial scan of the community.

The Q&A portion was lively. Many attendees said they could see a value in mapping their forest and the ground beneath the canopy. Community members viewed lidar as a way to record their territory and even promote responsible tourism. There was some hesitation about the potential for increased looting due to media attention or when the federal government released some of the mapping data. But most people felt prepared for that possibility thanks to decades of experience protecting their forest.

In the end, the community formally gave its consent to proceed. Still, consent is an ongoing process, and one must be prepared to stop at any point should the consenting party withdraw permission.

Aerial lidar can benefit all parties

Too often, in my experience, archaeologists remain unaware — or even defensive — when confronted with issues of Indigenous oppression and consent in aerial lidar research.

But another path is possible. Obtaining culturally sensitive informed consent could become a standard practice in aerial lidar research. Indigenous communities can become active collaborators rather than being treated as passive objects.

In Metzabok, our aerial mapping project was an act of relationship-building. We demonstrated that cutting-edge science can align with Indigenous autonomy and well-being when grounded in dialogue, transparency, respect and consent.

The real challenge is not mapping faster or in finer detail, but whether researchers can do so justly, humanely and with greater accountability to the peoples whose lands and ancestral remains we study. Done right, aerial lidar can spark a true revolution, aligning Western science and technology with Indigenous futures.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.