A lifesaving drug that can reverse an opioid overdose will be available on pharmacy shelves without a prescription this summer, a regulatory relaxation that experts herald as an important step in managing the U.S. opioid epidemic.

Currently, naloxone is officially classified as prescription-only but is also available from pharmacists in states with a standing order—a directive designed to increase access to public health interventions such as annual flu shots—or a similar protocol. At participating pharmacies, an individual doesn’t need a prescription with their name on it to access naloxone but does need to speak with a pharmacist in person.

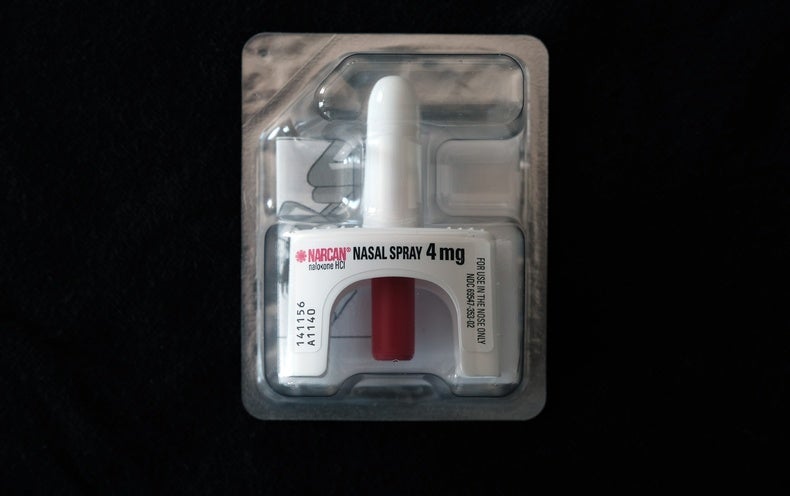

The Food and Drug Administration announced on March 29 that it had approved Narcan, a nasal spray containing the opioid-overdose-stopping drug naloxone, for distribution over the counter in the retail sections of pharmacies like a typical cough medicine or painkiller. In a statement at that time, Emergent BioSolutions, a company headquartered in Maryland that manufactures Narcan, said it expected the medication would hit shelves by late summer, although the drug’s retail price is not yet known.

The move comes as the opioid death toll continues to rise. According to the National Institutes of Health, more than 80,000 people in the U.S. died from an opioid overdose in 2021.

“We really need to do everything we possibly can to make a dent in the overdose death crisis here in the U.S.,” says Kimberly Sue, an assistant professor of medicine at the Yale University School of Medicine.

Scientific American spoke to some experts in harm reduction and opioid use disorder about what the FDA’s decision means, how naloxone works and what role it can play in stemming the crisis.

How does naloxone work?

During an overdose, molecules of opioids such as heroin, morphine or fentanyl bind to structures called mu opioid receptors throughout the body—especially those in the brain and gut. When enough opioid molecules bind to receptors in the brain, breathing begins to shut down.

Naloxone binds to those same receptors more strongly than opioids do, so it can physically knock opioids away from the receptors and stop an overdose in its tracks. And even though naloxone binds to the same receptors, it doesn’t produce the same effects—so it doesn’t cause a euphoric “high” like opioids do. The process isn’t foolproof: it might take multiple doses for naloxone to kick in, and its effect only lasts about half an hour. As it wears off, an overdose can resume—but naloxone buys crucial time to get medical help.

Naloxone can be administered intravenously in medical settings. Narcan, one nasal spray version, will be available over the counter under the new FDA approval. Another brand of nasal spray, Kloxxado, will continue to require a prescription.

What are the symptoms of an opioid overdose, and how is naloxone spray administered?

The two key symptoms of an opioid overdose are difficulty breathing and nonresponsiveness. A person’s skin can also become discolored, and the pupils of the eyes sometimes shrink to pinpricks.

Naloxone nasal spray is relatively simple to administer: insert the tip of the nozzle into one nostril and push the plunger in. If it turns out that someone doesn’t have opioids in their system, the procedure is still safe because naloxone only binds to mu opioid receptors. “We don’t have to worry about causing them harm if, for some reason, it’s not an overdose,” says Laura Palombi, a public health pharmacist at the University of Minnesota, who specializes in harm reduction—an approach that aims to reduce the dangers of drug use in a compassionate and nonjudgmental way.

After administering naloxone, call 911 and either perform rescue breathing if possible or turn the person on their side to reduce the risk of choking. If symptoms don’t subside within a few minutes, additional doses in alternating nostrils may be needed to stop the overdose. Palombi says she’s heard of cases requiring as many as eight sprays.

Harm reduction experts emphasize that naloxone will only counteract an opioid overdose. If someone is under the influence of alcohol or a different class of drug, this antidote won’t help. If a person has multiple drugs in their system, naloxone will only reverse the opioid overdose. “I would say definitely take a training on how to administer [Narcan],” says Allie McDevitt, a recovery case manager at Life House, a youth shelter in Minnesota. She used five doses of the drug to help someone who went into overdose near the organization. “It’s tough because until you’ve actually been in the situation, like many things, it’s easier said than done,” McDevitt says.

How will making naloxone available over the counter help people?

Naloxone is currently available only from pharmacists and through community harm reduction centers or similar programs. The FDA’s decision means this medication can also be sold online and at a range of stores, making it far more accessible to the public.

That’s important, experts say, because people who struggle with addiction-related shame can be reluctant to speak with a medical provider about getting naloxone. “I would say that stigma is our number one barrier to getting naloxone out in the community,” Palombi says. She hopes the move to make this medication available over the counter will also show people that it is safe. “All of us should have it in our household as a part of our first aid kit,” she says.

But experts still have a lot of questions about how the move will play out, especially in terms of cost. Estimates vary, but Palombi says the best price she can find now is still nearly $50 for a box of two Narcan doses—which is steep, considering that a single overdose may require several dispensers. Some health insurance programs currently cover naloxone, but they usually don’t cover over-the-counter medications.

Whether the price tag will shrink once the medicine no longer requires a prescription isn’t yet clear. “There have been examples where, when things move to [over the counter], it actually becomes in some ways more expensive,” says Jonathan Watanabe, a clinical pharmacist at the University of California, Irvine.

Sue also notes concerns about the price and says structural inequalities make plenty of her patients unable to afford even a $3 copay. “This will not solve getting it in the hands of people who are most vulnerable to overdose,” she says.

Palombi says community harm reduction centers may remain the best places for people on tight budgets to get naloxone because these organizations sometimes receive grants to help distribute the medication.

But Kavita Babu, a medical toxicologist at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, worries that lowering regulatory hurdles may actually disadvantage such organizations. “What you never want to hear is that because naloxone is now available over the counter, the funding for naloxone distribution programs has been reduced,” she says. Like others, Babu describes the FDA’s move as incremental progress. “Over the counter is better than prescription; free is better than over the counter,” she says.

Will naloxone alone be enough?

Some in the field say the opioid crisis in the U.S. will require a lot more than naloxone to tackle—and that this would be the case even if the drug was easier and cheaper to get.

“This is a really important step, but it’s not all the way to the goal line,” says Watanabe, who directs the U.C. Irvine Center for Data-Driven Drugs Research and Policy. In addition to addressing the economics of naloxone access, he has called for better access to buprenorphine and methadone, long-term medications that treat opioid use disorder.

Even before the decision to sell it over the counter, “we’ve given away naloxone like candy for the last several years, and opioid death rates have continued to rise,” says Edward Boyer, a medical toxicologist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Emergent BioSolutions says 44 million doses of Narcan have been distributed since 2016, when it first became available. But opioid overdose deaths have nearly doubled since then. Some 47,000 people died of such an overdose in 2017, compared with 80,000 in 2021, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Babu blames that rise on fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that’s much stronger than morphine or heroin and is often mixed into other drugs, catching people unaware. “I hate to think about what these numbers could look like without the programs that are currently in place and the energy and thought and funding that’re being put into preventing overdose deaths,” she says.

Sue emphasizes that behind all these numbers are real people. “Those are our family, our friends, our community, our patients,” she says. “Every opioid overdose death is a policy failure.”