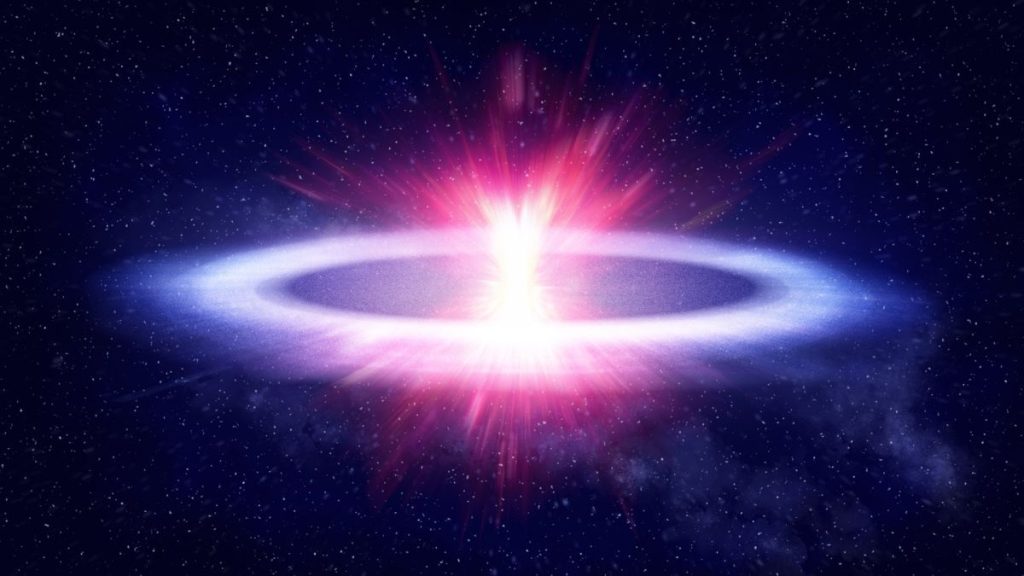

A weird cosmic explosion that stunned scientists in 2018 just got even stranger. A new analysis of the polarized light from the first recorded fast blue optical transient (FBOT) explosion — officially known as AT2018cow and nicknamed “the Cow” — revealed that the blast is the most asymmetrical explosion ever seen by astronomers, bursting into space in a flattened, pancake-like shape rather than a typical sphere.

The shape of the blast, which is around the size of the solar system and occurred 180 million light-years from Earth, may challenge scientists’ perceptions of how explosive events like FBOTs occur.

“This discovery tells us that these explosions aren’t spherically symmetric — in fact, the disk we think we’ve observed is really flat,” Justyn Maund (opens in new tab), a senior lecturer in astrophysics at the University of Sheffield in the U.K. and lead author of the new research, told Live Science via email. “This means that any model that wants to explain these FBOTs has to confront the fact that these are not round events.”

FBOTs like the Cow were already a major puzzle for scientists. Since the discovery of the Cow in 2018, only four other similar transients have been sighted, and as a result, very little is known about FBOTs or what causes them. But one thing is clear: They don’t behave like typical supernovas, the most common type of space explosion, which occur when massive stars run out of nuclear fuel and collapse under their own gravity.

“FBOTs are bright, they’re really bright — brighter than some superluminous supernovae — but they suddenly appear, and then their brightness drops like a stone!” Maund said. “Unlike regular supernovae, there are no radioactive elements to power the brightness, so the power has to come from somewhere else.”

On June 16, 2018, an oddly-shaped cosmic explosion called “the Cow” blazed out of the Hercules constellation 200 million light-years away. Scientists still aren’t sure what caused the blast. (Image credit: Raffaella Margutti/Northwestern University)

In their new research, Maund and his team took another look at the light from the Cow first recorded in June 2018, this time studying how the light was polarized — how the vibrations in the light waves traveled in a single plane. While this analysis of the Cow doesn’t reveal the origins of FBOTs just yet, the Cow’s flatness shows that FBOTs are even more distinct from supernovas than scientists previously thought.

Related: Brightest gamma-ray burst ever detected defies explanation

“On the first night, we saw a massive spike in the polarization and then it fell down,” Maund said. “The spike reached 7% on the first night. For supernovae we’ve never seen such a high level of polarization or polarization that’s evolved so quickly — so this is not what we’re used to at all.”

These polarization observations allowed the team to determine the Cow’s strange shape. Light from the Cow was measured using the Liverpool Telescope, whose primary mirror is only 6.5 feet (2 meters) in diameter. The team used these data to create a 3D model of the explosion, with polarization allowing them to reconstruct it as if it had been spotted by a telescope with a diameter of around 388 miles (625 kilometers). This allowed them to map the explosion to its edges, revealing just how flat it actually was.

“Based on previous work on supernovae we see things that look a bit oblate, a bit like a hamburger, or a bit prolate, more like a rugby ball , but not hugely aspherical,” Maund said. “So when this number came out of the analysis, I and my co-authors redid all of the data reduction and analysis multiple times to check!”

The team now intends to search for more FBOTs to see how many show polarization similar to the Cow’s, and thus determine if they are also pancake-like disks. The researchers will collect these data via the Legacy Survey of Space and Time survey, which will be conducted by the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile.

The team hopes this deeper look at the Cow may shed light on these rare, powerful events. Maund currently has a few ideas about what could potentially cause FBOTs.

“The cause of FBOTs could be the disruption of a star passing a black hole or a failed supernova in which the core collapses and doesn’t cause a supernova, but instead it collapses into a black hole or neutron star and starts chewing up the insides, and that’s powering what we see as the FBOT,” Maund said.

The team’s research was published March 30 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (opens in new tab).