Just before midnight at the close of a hot summer day in 1916, a natural gas pocket exploded 120 feet beneath the waves of Lake Erie. It happened during work on Cleveland’s newest waterworks tunnel, a 10-foot-wide underwater artery designed to pull in water from about five miles out, beyond the city’s polluted shoreline. The blast left twisted conduit pipes littering the tunnel floor and tore up railroad tracks inside the corridor, with noxious smoke curling off the rubble. When the dust settled, 11 tunnel workers were dead.

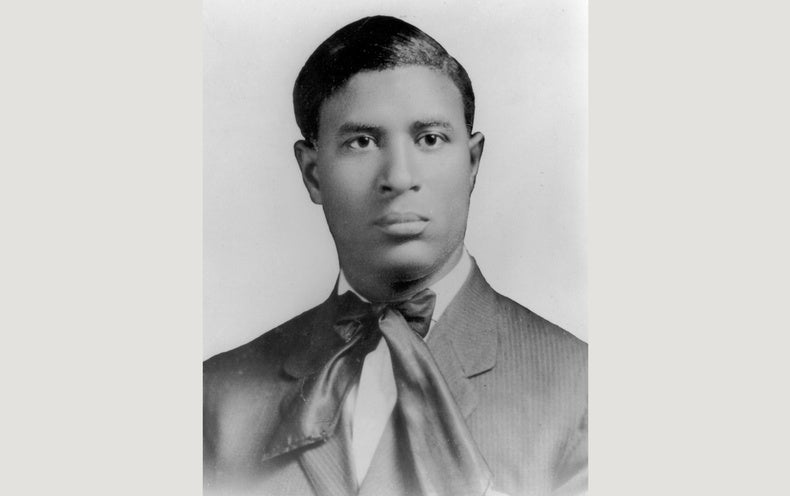

Two rescue parties entered the tunnel searching for survivors. But they lacked proper safety equipment for the smoke and fumes; 11 of the 18 rescuers died. Some 11 hours later, desperate to save anyone still alive, the Cleveland Police turned to Garrett A. Morgan—a local inventor who called himself “the Black Edison”—and the gas mask he had patented two years earlier.

“He rustled his brother Frank,” says the inventor’s granddaughter, Sandra Morgan. “They threw a bunch of gas masks in the car—remember, they were selling these things—and in their pajamas, drove down to the lakefront.”

Safely through the smoke and fumes

Morgan’s invention was born out of tragedy. A fire enveloped New York’s Triangle Shirtwaist Company on March 25, 1911, killing 146 garment workers—most of them young female immigrants who were locked in the factory. The incident put the inadequacy of fire codes and safety equipment on national display, and Morgan, who had himself once worked in Cleveland’s booming garment industry, decided to try his hand at an effective mask. He attacked a problem that had stymied inventors for years: smoke inhalation.

“Pulmonary complications following smoke inhalation account for about 77 percent of fire-related deaths,” says Sumita Khatri, a pulmonologist at Cleveland Clinic, “and it’s mostly from carbon monoxide poisoning. Carbon monoxide is very attracted to hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in our red blood cells, and attaches to the red blood cells much easier than oxygen. Blood cells need to release oxygen to the body. But when they are bound by carbon monoxide, oxygen isn’t getting to your muscles, tissues, organs and brain. You’re basically suffocating from the inside, at the cellular level.”

Cover of an advertising pamphlet showing Morgan’s invention, the national safety hood and smoke protector, circa 1914. Credit: Western Reserve Historical Society

Morgan knew carbon monoxide tends to linger at roughly the level of a standing person’s head, whereas cleaner air hovers closer to the feet. So, he designed his device to draw air through a long tube that hung near the ground like a tail. It diverged at tailbone level into two hoses that snaked up either side of the wearer’s rib cage and below the underarms, finally entering the mask (a hood resembling a beekeeper’s helmet) like serpentine walrus tusks.

From behind, the system resembled a “Y,” and its dangling intake tube was reminiscent of an elephant’s trunk. These animals, in fact, seem to have fired up Morgan’s imagination: “As I understand it, he took inspiration from elephants at the circus,” Sandra says. “It was boiling hot, and he saw the elephants stick their trunks out of the tent to get fresh air.”

But Morgan’s brilliant observation, and the simple but practical device that resulted from it, proved difficult to sell. His father was the son of Confederate General John Hunt Morgan and an enslaved Black woman, Sandra says, and Morgan’s mother was Black, which meant the inventor was fully subject to racism. He attended school through sixth grade and was largely self-taught. But his ingenuity eventually won out. After many failed attempts to sell what he called his “safety hood,” Morgan created a theatrical scheme to bypass potential buyers’ bigotry. In 1914, he hired a white actor to pose as the inventor. Morgan then disguised himself, filled a tent with noxious smoke, and cued the actor to entertain the crowd as Morgan strapped on his breathing device and entered the tent—where he waited for nearly half an hour before emerging safely to an aghast audience. Brisk sales followed, and newspapers reported the demonstration—and that’s how the Cleveland Police Department knew about Morgan’s device.

An overlooked hero

Cleveland in 1916 was swelling to become the nation’s fifth-largest city. Its growing population was overwhelming the sewer system and dangerously contaminating the Lake Erie water supply. Waterworks tunnels, extending miles beyond the worst of the pollution, offered the promise of cleaner drinking water.

To create the tunnels, workers known as “sandhogs” had to burrow beneath the lake bed through sand, gypsum, limestone—and mammoth reserves of natural gas. The latter were formed millions of years ago after dead plants and animals mingled with silt, sand or calcium bicarbonate and over time became buried deep under Lake Erie. Multiple layers of sediment added pressure and heat to this mixture, eventually transforming the carbon and hydrogen it contained into natural gas. More than three trillion cubic feet of it lie beneath the lake. And just before midnight on July 24, 1916, the sandhogs struck an explosive pocket.

By the time Morgan was called in and descended the tunnel, bodies from the two previous rescue parties lay strewn across the tube. But eight men were still alive, and Morgan hauled them all to safety.

The next day, though, reports in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune and other newspapers failed to mention Morgan. “The foreman and others were given a big cash bonus, medals—they were recognized in the paper,” Sandra says. “My grandfather was not.”

Morgan was indignant. “He wrote a scorching letter to Cleveland Mayor Harry Davis,” Sandra says, quoting from a copy: “I am not a well-educated man; however, I have a Ph.D. from the school of hard knocks and cruel treatment.”

Some five years later, in the early 1920s, the inventor witnessed a horrific accident between an automobile and a horse-drawn cart at an intersection. Once again, his ingenuity kicked in. Before Morgan, traffic signals only had two positions: stop and go. “My grandfather’s great improvement,” Sandra says, “was the ‘all hold’—what is now the amber light.” Morgan patented the three-position traffic signal in 1923 and soon sold the idea to General Electric for $40,000 (the equivalent of about $610,000 today). He purchased 250 acres later that year in Wakeman, Ohio, and transformed it into an African American country club complete with a party room and dance hall.

Garrett Augustus Morgan died at the Cleveland Clinic on July 27, 1963, “after a lingering illness,” reported the popular African American newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier. “He was 87 years old, being blind for the past 15 years.” Half a century later, his invention went on display at the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture—honoring a brilliant inventor who risked his life to save eight men and, through his inventions, continued to save the lives of countless others.