For the second time, an experimental drug has been shown to reduce the cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s disease. On 3 May, pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly announced in a press release that its monoclonal antibody donanemab slowed mental decline by 35% for some participants in a 1,736-person trial — a rate comparable to that for competitor drug lecanemab. But researchers warn that until the full results are published, questions remain as to the drug’s clinical usefulness, as well as whether the modest benefit outweighs the risk of harmful side effects.

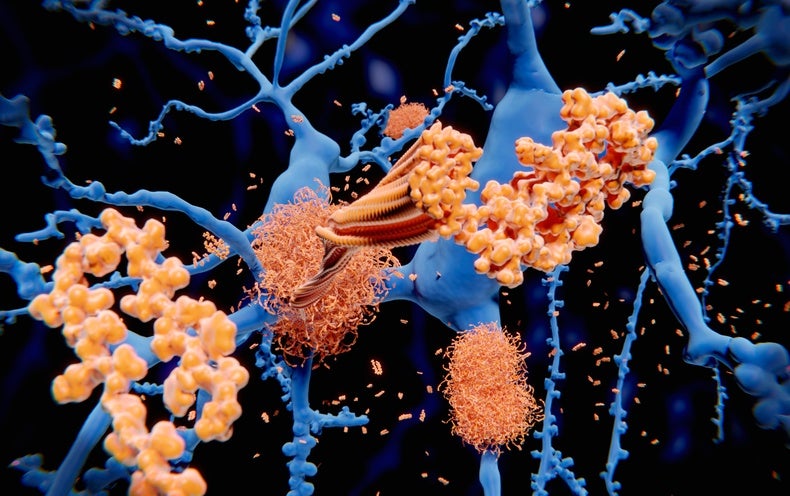

Like lecanemab, donanemab targets amyloid protein, which is thought to cause dementia by accumulating in the brain and damaging neurons. The trial results provide strong evidence that amyloid is a key driver of Alzheimer’s, says Jeffrey Cummings, a neuroscientist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “These are transformative in an enormously important way from a scientific point of view,” he adds. “They’re terrific.”

But Marsel Mesulam, a neurologist at Northwestern University in Chicago, is more cautious. “The results that are described are extremely significant and impressive, but clinically their significance is doubtful,” he says, adding that the modest effect suggests that factors other than amyloid contribute to Alzheimer’s disease progression. “We’re heading to a new era — there’s room to cheer, but it’s an era that should make us all very sober, realizing that there will be no single magic bullet.”

In the press release, Eli Lilly said that people with mild Alzheimer’s who received donanemab showed 35% less clinical decline over 18 months than did those who received a placebo, and 40% less decline in their ability to perform daily tasks. The company says that it will present the full results at a conference in July and publish them in a peer-reviewed journal. It plans to apply for approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the next two months.

Promising treatments

FDA approval would make donanemab the third new Alzheimer’s treatment in two years. In January, the agency granted accelerated approval to lecanemab, made by Biogen in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Eisai in Tokyo. A study1 published in November showed that lecanemab slowed cognitive decline in 1,800 patients by 27% over 18 months. The FDA had previously approved aducanumab, also made by Biogen and Eisai, on the basis of evidence that it could reduce amyloid plaques in the brain, although it is still unclear whether this leads to a meaningful clinical benefit for people with the disease.

Eli Lilly’s donanemab trial differed from Biogen’s lecanemab one in that people stopped taking the drug once their amyloid levels had dropped below a certain threshold. “The rationale is, if the target is gone, why keep shooting?” Cummings says. According to the press release, about half of the trial participants were able to stop taking the drug in less than one year.

Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research, a non-profit think tank in Washington DC, worries that stopping the drug could cause the disease to rebound or worsen, as is the case with many psychiatric drugs. She warns that longer-term follow-up studies will be needed. “Any time you’re doing anything that affects the brain, you really do have to be cautious,” she says.

Eli Lilly also found that donanemab worked best in people whose brains contained only moderate levels of another protein, called tau, that is also associated with Alzheimer’s progression. The company had calculated its results among its 1,182 trial participants who had moderate tau levels, but said that the improvement was still statistically significant when they combined these patients with the 552 who had high levels of tau.

Brent Forester, a geriatric psychiatrist at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, says it’s “fascinating” that removing amyloid also affects tau: the relationship between the two proteins, and their respective roles in disease progression are not fully understood. “If we could understand that better, we might understand why removing amyloid might have a clinical effect,” he says.

Bleeding and seizures

Like lecanemab, donanemab carries a high risk of side effects — particularly a set of conditions called amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) that can lead to seizures and bleeding in the brain. Researchers think that by attacking amyloid plaques, the antibodies inadvertently weaken blood vessels in the brain, and the effects are especially pronounced among people who are taking anticoagulant drugs. Eli Lilly’s press release said that ARIA rates were several times higher in people who received donanemab than in those who received placebos, and three patients in the trial died after experiencing the condition.

“The side effect is the biggest concern for all of us right now,” says Forester, who led earlier trials of donanemab and is currently working on a lecanemab trial. He adds that people with mild cognitive impairment function fairly well, and that even three deaths might be enough to signal that the risk of side effects outweighs the benefit of taking the drug.

Questions also remain about information that is missing from the announcement, including whether donanemab worked at all among people who had high levels of tau. “This whole publication-by-press-release is really bad,” Zuckerman says.

Furthermore, the results that Eli Lilly released show only a slowing of cognitive decline relative to the placebo group, rather than how much donanemab affects the absolute rate of a person’s decline. It’s unclear, Zuckerman says, whether that difference is great enough to be noticeable to people with Alzheimer’s and their families.

With at least three monoclonal antibodies soon to be on the market, Mesulam worries that excitement around them will decrease drug companies’ enthusiasm for developing drugs for Alzheimer’s targets other than amyloid. “The next 20 to 25 years will be taken up by better amyloid drugs,” he says. The Alzheimer’s market is likely to be very lucrative for drug companies — lecanemab, for instance, costs more than US$26,000 per year of treatment — but Mesulam worries that the cost of Alzheimer’s drugs will strain the US health-care system.

Still, the initial results provide “further support that this therapy will have some role with the right patients at the right time in illness”, Forester says. “I’m cautiously optimistic.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on May 4, 2023.