For millennia, an ethnic group in what’s now southwest China placed their dead in “hanging coffins” on cliffsides, but their identity has long eluded researchers. Now, a new genetic study reveals that this ancient funeral tradition was carried out by ancestors of people who still live in the region today.

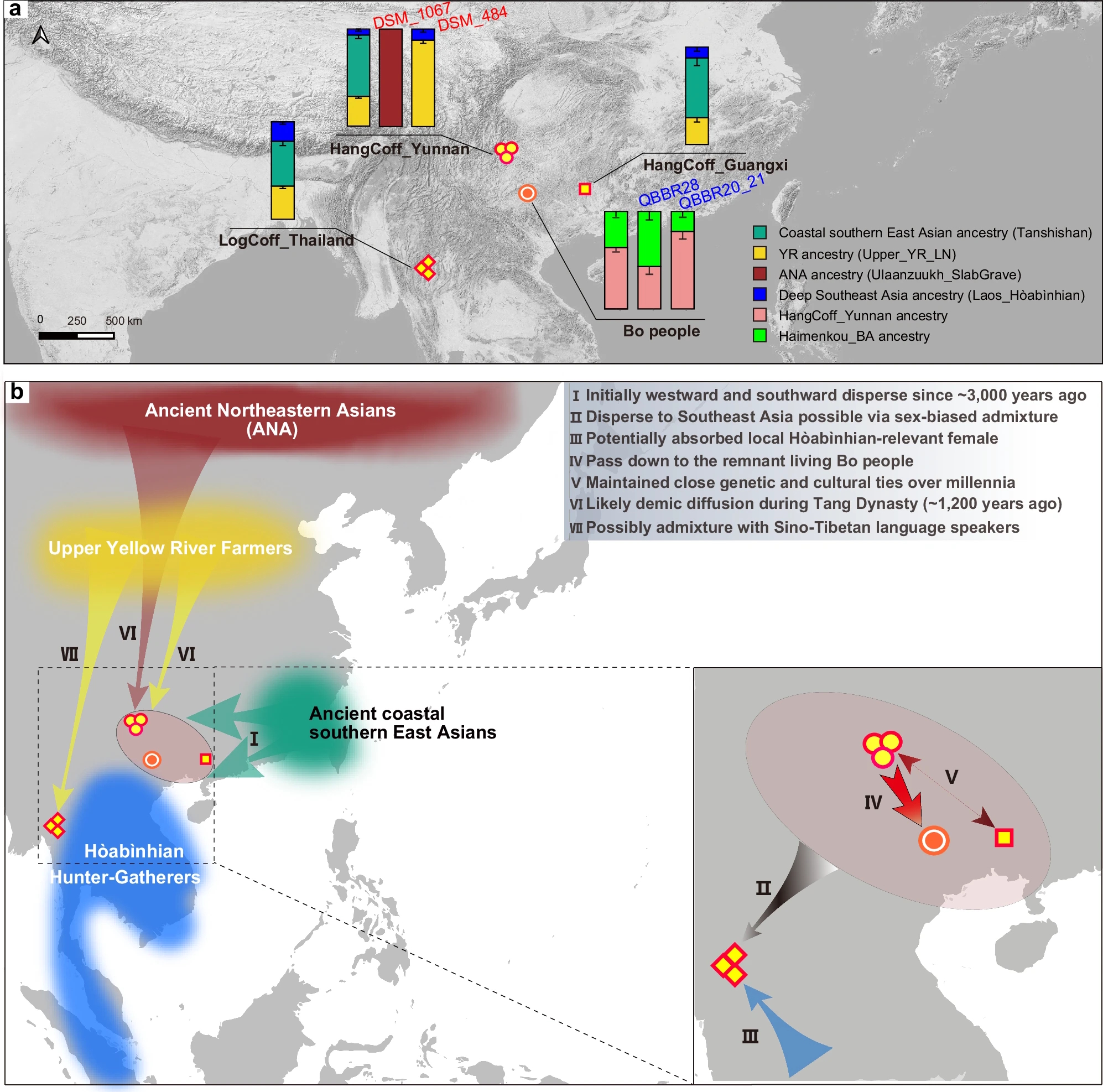

The researchers also found genetic links between the ancient people who practiced “hanging coffin” tradition — in which ancient wooden coffins were pegged onto exposed cliffs — and Neolithic (“New Stone Age”) people who lived on the coasts of southern China and Southeast Asia.

Over the past 30 years, researchers have documented hundreds of hanging coffins throughout China and Southeast Asia, the researchers wrote in the study. Historical texts and oral traditions note that a small ethnic group known as the Bo people were behind the practice, but for the new study, researchers turned to genetics to solve the mystery once and for all.

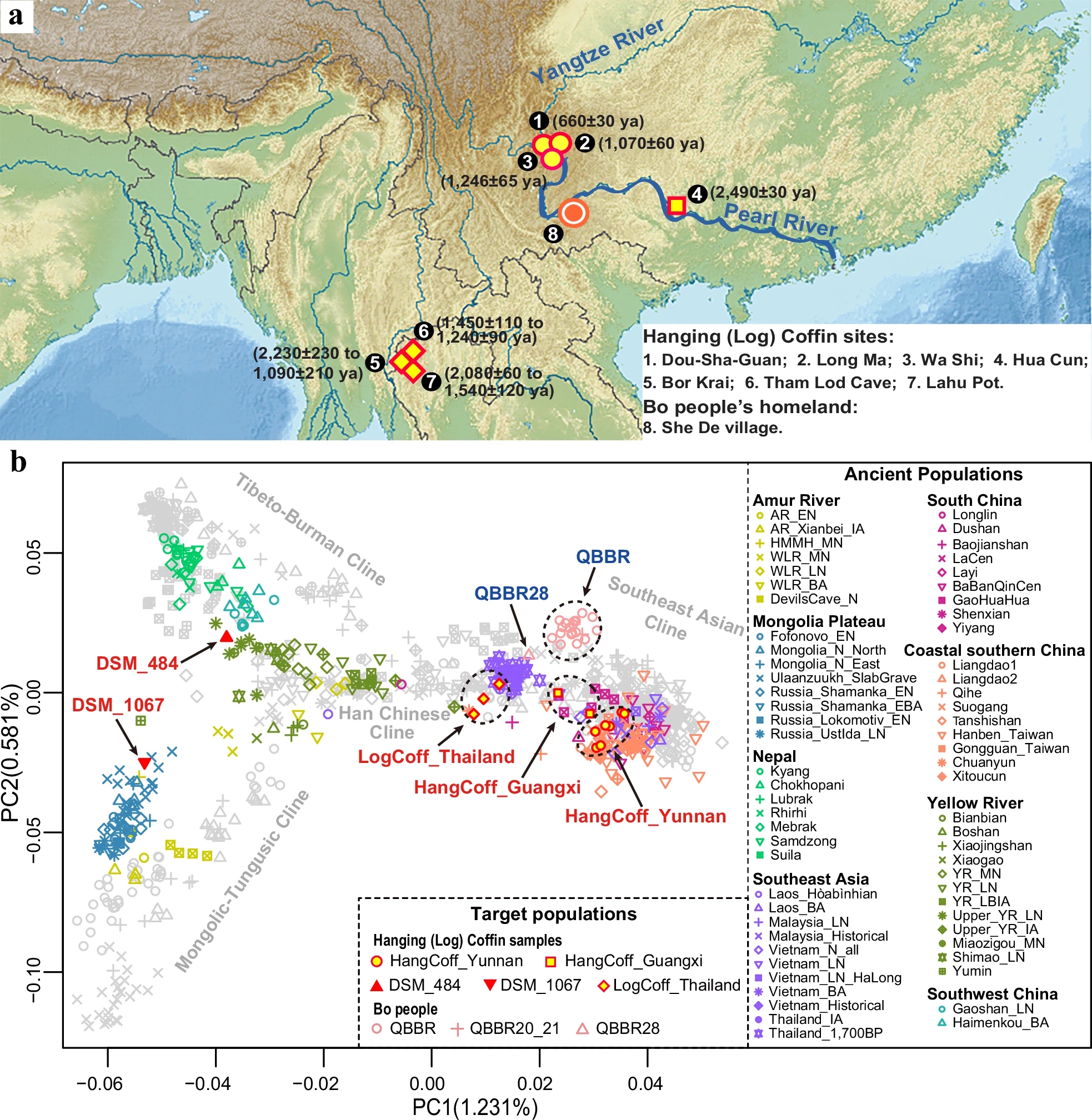

In their investigation, the researchers analyzed the genetics of 11 individuals, some of whom lived more than 2,000 years ago, at four “hanging coffin” sites in China.

They supplemented their study by examining the remains of four individuals contained within ancient “log coffins” discovered in a cave in northwestern Thailand, the oldest of which dates to 2,300 years ago, and with 30 genomes from living people of Bo descent.

The results indicate that the “hanging coffin” people — and, therefore, the modern Bo people — had genetic links to groups who lived between 4,000 and 4,500 years ago, during the Neolithic period in this region from about 10,000 B.C. until about 2000 B.C.

“The genetic traces left behind provide compelling evidence of a shared origin and cultural continuity that transcends modern national boundaries,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Hanging coffins

Dozens of “hanging coffin” sites are found throughout southern China and in Taiwan, where it was once a popular funerary style. However, funerals of this type stopped hundreds of years ago, during China’s Ming dynasty between 1368 and 1644.

The researchers noted an early reference dates to the Yuan dynasty, from about 1279 to 1368. “Coffins set high are considered auspicious,” a chronicler wrote.”The higher they are, the more propitious they are for the dead. Furthermore, those whose coffins fell to the ground were considered more fortunate.”

A few thousand people of Bo descent now live in China’s southern Yunnan province, where they are categorized as part of the official Yi ethnic group, although their language and traditions are unique, according to the study.

But their ancestral culture was once much more widespread, encompassing regions that are now parts of Thailand, Laos, Vietnam and Taiwan, the researchers wrote. It seems the tradition of “hanging coffins” originated at least 3,400 years ago in the Wuyi Mountains of China’s southeastern Fujian province.

Shared ancestry

The remains from the ancient “log coffins” in northwest Thailand also showed remarkable genetic similarities to the people interred in the “hanging coffins,” the researchers found, indicating these peoples had shared ancestries.

In Thailand, the coffins were made by splitting the log of a tree in two lengthways and hollowing out one side while using the other side as a coffin lid. The coffins were then interred within a cave, often on wooden supports or on high rock ledges.

Those findings, as well as evidence from other archaeological sites throughout Asia, suggest the “hanging coffin” people were a branch of the ancient Tai-Kadai-speaking peoples who occupied much of southern China before the dominance of the Han ethnicity from about the first century B.C., the researchers reported.

According to Thailand’s Chulalongkorn University, the ancient speakers of the Tai-Kadai languages (also known as the Kra-Dai languages) have given the name to the modern nation of Thailand and are the ancestors of millions of non-Han Chinese people, especially in the south of that country.

But the key finding of the study is the ancient identity of the “hanging coffin” people, the researchers wrote. Regional folklore referred to the Bo people “with names such as ‘Subjugators of the Sky’ and ‘Sons of the Cliffs,’ and even described [them] as being capable of flight,” the team wrote in the study. Now, genetics firmly connects the Bo people to those buried in the hanging coffins.

“Approximately 600 years after the custom vanished from historical records, we found that the Bo people are the direct descendants of the Hanging Coffin custom’s practitioners,” the researchers wrote.