The Tonga underwater volcanic eruption rivaled the strength of the largest U.S. nuclear bomb and produced a “mega-tsunami” nearly the height of a 30-story skyscraper, a recent study finds (opens in new tab).

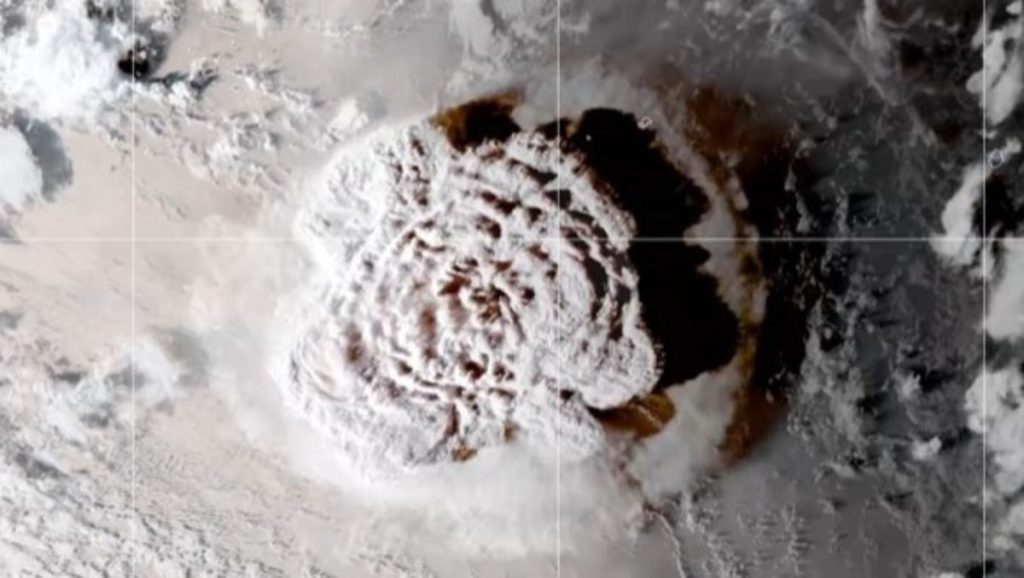

On Jan. 15, 2022, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai submarine volcano — a large, cone-shaped mountain located near the islands of the Kingdom of Tonga in the South Pacific — erupted with a violent explosion. The eruption generated the highest-ever recorded volcanic plume, which reached 35 miles (57 kilometers) tall. The outburst triggered tsunamis as far away as the Caribbean, as well as atmospheric waves that traveled around the globe several times.

To determine the strength of the eruption, scientists collected before-and-after satellite optical and radar images, drone maps and field observations to generate a computer simulation of the catastrophe.

They discovered that the explosion may have been as strong as 15 megatons (millions of tons) of TNT, making it about as strong as the United States’ largest nuclear detonation, Castle Bravo, in 1954, according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation (opens in new tab). It would also make the eruption “the largest natural explosion in more than a century,” study lead author Sam Purkis (opens in new tab), professor and chair of the Department of Marine Geosciences the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, told Live Science in an email.

Related: Is the Yellowstone supervolcano really ‘due’ for an eruption?

The eruption released at least five blasts, generating a tsunami up to 279 feet (85 m) high one minute after the largest explosion. This led to waves as high as 147 feet (45 m) on the Tongan island Tofua and 55 feet (17 m) on Tongatapu, they found.

“Our data prove that the waves generated by the explosion comfortably place Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai in the ‘mega-tsunami’ league,” said Purkis, who is also chief scientist at the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation in Annapolis, Maryland. “We have observed an event in real time using modern instrumentation that had previously only been recognized in antiquity. This is all incredibly exciting.”

Until now, the extent of the eruption and its aftermath had proved elusive due to the scarcity of scientific instruments near the site of the eruption. “Obscured from casual view, submarine volcanoes are much harder to monitor than volcanoes on land,” Purkis said.

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano on December 24, a month before the eruption. (Image credit: Maxar/Getty Images)

The scientists found that the complex, shallow nature of the region’s underwater terrain helped to trap low-velocity waves from the eruption. This, in turn, helped generate a mega-tsunami that lasted more than an hour. “We show how submarine volcanic eruptions can generate massive tsunami,” Purkis said. “A series of small blasts hailed the arrival of the big one, which generated the largest tsunami.”

The scientists said the strength of the 2022 eruption rivaled that of the 1883 eruption of Krakatau that killed more than 36,000 people. In contrast, the 2022 eruption killed an estimated six people.

The low death toll is a testament to the effectiveness of safety drills and awareness efforts carried out in Tonga in the years before the eruption, Purkis said. The eruption’s relatively distant location from urban centers also may have saved Tonga from a worse fate, the scientists noted.

The computer simulations also revealed that the coral reefs that fringe the Tongan islands helped suppress the waves that ultimately made their way to shore. This finding suggests these reefs may have experienced substantial damage, Purkis said.

Still, “clearly the reefs can recover from such damage,” Purkis noted. “Archaeological evidence pins a major tsunami in the mid-15th century with runup heights up to 30 meters [98 feet] — that is, similar in size to the 2022 event.” However, “when I surveyed the coral reefs of the Tongan archipelago with the Living Oceans Foundation in 2013, we found the reefs to be healthy and vibrant. The damage from the event 500 years ago had been erased.”

Future research should focus on the best way to place sensors to record data from submarine volcanoes and the coastlines of vulnerable islands as “an effective means of keeping tabs on submarine volcanoes,” Purkis said.

The scientists published their findings (opens in new tab) online April 14 in the journal Science Advances.