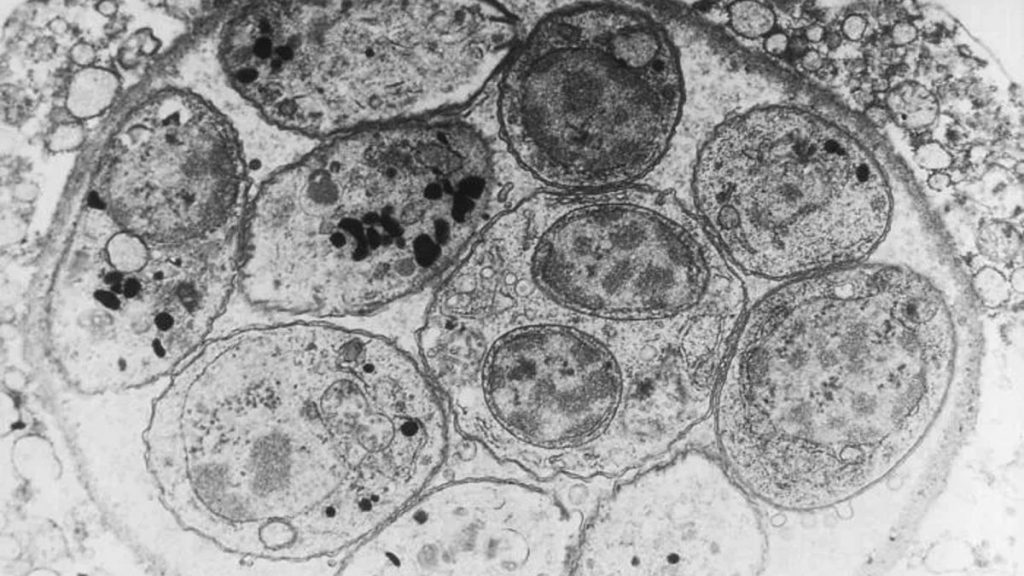

A Toxoplasma gondii tissue cyst. (Image credit: CDC) (opens in new tab)

Toxoplasma gondii is a single-celled protozoan parasite that invades the cells of a variety of host organisms, including humans, and causes a disease known as toxoplasmosis. T. gondii is sometimes nicknamed the “mind-control parasite” because toxoplasmosis can cause a range of neurological and behavioural changes in infected animals, although most human infections have no clear symptoms.

The pathogen is one of the most common infectious parasites in the world and could lay dormant in up to half of the world’s population, as well as almost any warm-blooded animal species. But there is still much we don’t know about this extremely weird parasite.

From its unusual affinity for cats to its ties to schizophrenia, here are 10 surprising facts about T. gondii.

There are many ways you can be infected with T. gondii

Washing your hands properly after gardening and cleaning out your cat’s litter box can help prevent T. gondii infections. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

Humans mainly become infected with T. gondii by accidentally ingesting the parasites’ eggs, or oocytes, which are excreted exclusively by cats. This can happen when people drink contaminated water, clean out litter boxes or fail to wash their hands properly after gardening or ingesting contaminated foods, such as unwashed vegetables, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (opens in new tab).

People can also be infected by eating the undercooked meat of other infected animals, such as pigs, sheep and shellfish, which can develop tiny, infectious cysts, or bradyzoites, after they consume oocytes from the environment, according to the CDC.

T. gondii can also be transferred from mothers to babies in the womb, as well as during organ transplants and blood transfusions, but this is much rarer, according to the CDC

Most people have no symptoms at all

Most people infected with T. gondii will never know. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

A majority of people who become infected by T. gondii have no idea because they display no symptoms. Some people will develop mild flu-like symptoms for a few weeks as their body fights off the infection, but they normally have no long-term complications, according to the CDC.

However, pregnant women, infants and people with weakened immune systems can develop severe cases of toxoplasmosis that can cause long-term damage to the brain, eyes or other organs, according to the CDC. Occasionally, T. gondii can remain dormant in cells for years after infection before toxoplasmosis begins.

If you think you might have toxoplasmosis then you can ask for a simple blood test from your doctor.

Toxoplasmosis HAS a cure

It is a myth that toxoplasmosis has no cure. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

Doctors can treat toxoplasmosis using a combination of drugs such as pyrimethamine with folinic acid or sulfadiazine, according to the CDC (opens in new tab).

However, unless a person is experiencing a severe infection or are at high risk doctors usually don’t prescribe anything, as it is often better to let the immune system fight off the disease on its own.

Once a person has been infected with T. gondii then the parasite can lay dormant in your system for years, or even the rest of your life, according to the CDC. This may be the origin of the myth that there is no cure for toxoplasmosis. While having the disease lie dormant may sound menacing, it’s rare for the parasite to reactivate and sicken a person laterThere is currently no human vaccine for T. gondii but, in the U.K., farmers can provide their sheep with lifetime protection from the parasite by using the Toxovax vaccine, according to manufacturer MSD Animal Health Hub (opens in new tab).

Up to half of humans are infected

As many as 50% of the world’s population may have a T. gondii infection. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

Because it can be easily transmitted to humans via multiple pathways and often goes unnoticed by infected individuals, T. gondii is one of the most common infectious parasites in humans.

A 2014 study published in journal PLOS One (opens in new tab) estimated that between 30% and 50% of the global population could be infected with or have been infected with T. gondii. But infection rates likely vary significantly in different parts of the world. For example, the CDC estimates that around 40 million Americans, or around 12% of the population, may have a T. gondii infection. But a 2020 study published in the journal Scientific Reports (opens in new tab) found that around 64% of pregnant women in Ethiopia have been infected with T. gondii at some point in their life.

T. gondii has been linked to schizophrenia and other neurological disorders

Several studies have linked T. gondii infections to neurological disorders. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

One of the parasite’s most frightening — and most controversial— possible effects is its impact on the mind. In rats and other animals, it can cause behavioral changes (see more below) and it has been linked to several different neurological disorders in humans too.

Two of the most noteworthy conditions to be linked to T. gondii are schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

In 2006, a study published in the journal Biological Psychiatry (opens in new tab) first suggested that babies that contract T. gondii in the womb had higher rates of schizophrenia later in life than those who were not exposed prenatally. In 2014, a study published in The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease (opens in new tab) showed that people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were more likely to have T. gondii antibodies in their system, which are left behind from a previous infection.

T. gondii has also been linked to changes in human behaviour, some of which could be deadly. In 2015, a study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research (opens in new tab) suggested that T. gondii infections could make people more aggressive and impulsive, potentially even increasing the likelihood suicide.

But the relationship between T. gondii and the brain is still unclear

Not everyone agrees that T. gondii can play a role in neurological disorders. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

Although several studies have tied T. gondii to neurological disorders, it is too early to say the parasite is directly or indirectly responsible for any of these conditions.

Other studies, meanwhile, have called these types of links into question.

In 2016, a study published in the journal PLOS One (opens in new tab), which looked at more than 800 individuals born with T. gondii antibodies, found that “there was little evidence that T. gondii was related to increased risk of psychiatric disorder, poor impulse control, personality aberrations or neurocognitive impairment.”

Almost all warm-blooded animals can be infected

Magellanic penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus) are one surprising species that are at risk from toxoplasmosis. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

Scientists have found traces of T. gondii infection in a wide array of different endothermic animals, including all major livestock species.

In 2005, a study published in the International Journal of Parasitology (opens in new tab) revealed that T. gondii played a role in the population decline of sea otters (Enhydra lutris) in California, with up to 38% of dead otters having been infected. Researchers suspect that agricultural run-off from contaminated soils could have introduced T. gondii oocysts to the otters’ preferred food, sea kelp.

T. gondii can also pose a serious risk to penguins. In 2019, a study published in the journal Veterinary Parasitology (opens in new tab) found that around 42% of Magellanic penguins (Spheniscus magellanicus) on Magdalena Island, Chile, had been infected by T. gondii, despite the fact that the island had no cats, meaning infections were likely acquired from humans.

T. gondii can only reproduce inside cats

T. gondii needs a feline host to reproduce. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

Despite being found in a wide range of animals, T. gondii has only ever been observed reproducing in species from the family Felidae, which includes house cats and their wild relatives such as lions, cheetahs and tigers. House cats are believed to be the parasite’s preferred host.

No one knows why T. gondii cannot reproduce inside other infected animals, but it means that cat feces is the only route that the parasite can enter the environment from.

As of 2018, an estimated 373 million pet cats roam theEarth, according to Statistica (opens in new tab), with possibly hundreds of millions of unregistered stray cats as well.

Cats can only release the infectious oocytes for between one and three weeks after they become infected, after which they can no longer spread the parasites.

Rodents and small birds act as a jumping off point for T. gondii between cat infections. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

Although T. gondii can only reproduce inside cats, it is also regularly found in most rodents and several bird species.

These animals act as intermediate hosts, or a stopping off point between two different feline hosts. For example, a bird could become infected by T. gondii after eating seeds on top of dirt that had been contaminated by cat feces. That bird could then grow an infectious cyst in its body before being caught and eaten by a cat, who then becomes infected.

As a result, rodents and birds play a key role in the success of T. gondii because they are the main way cats become infected.

Infected rodents are more fearless

Increased fearlessness in rodents makes them more likely to be eaten by cats. (Image credit: Shutterstock) (opens in new tab)

Rodents infected with T. gondii seem to lose their typical fear of cats, or more specifically, their fear of cat urine.

A 2011 study in PLOS ONE (opens in new tab) suggested that infected rats start to feel a type of “sexual attraction” to the smell of cat urine, rather than their usual defensive response to the scent. If true, it would make infected rats more likely to live near cats, which would increase the chances of them being preyed upon. A follow-up study published in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases (opens in new tab) in 2011 repeated the experiment in humans, but although infected men were slightly more attracted to the scent of cat urine, women were not.

A 2020 study of mice published in the journal Cell Reports (opens in new tab) also showed that T. gondii can reduce general anxiety and increase explorative behavior in infected mice.

Live Science contributor Stephanie Bucklin contributed to this article.