Ed note: To protect the identity and privacy of the following sources, only first names of dating app users are included.

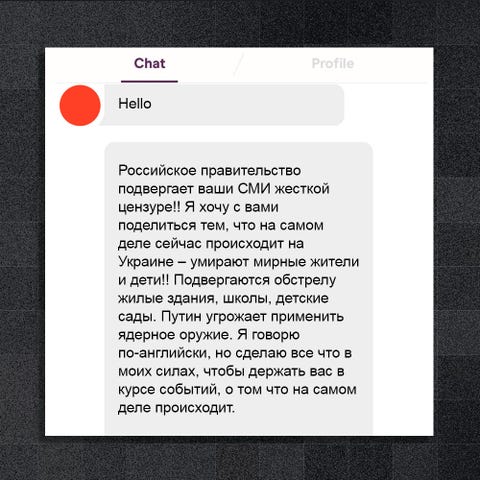

Nora logged onto Badoo and cued up a new message—in Russian.

“Because your media is being censored, I want to share what is happening—this is the reality: Ukrainian civilians and children are being killed. Residential buildings, schools, and kindergartens are being bombed. Putin threatens nuclear war. Please match me. I am an English speaker but will do my best to keep you informed of what is happening.”

She sent the message to no less than 50 people on the dating app, founded by Russian entrepreneur Andrey Andreev, receiving 20 or so replies before finding out that her account had been temporarily blocked.

For several weeks, the 32-year-old Bulgarian IT consultant based in New York City had only consumed news about the Russian invasion. She even had a group chat with her friends in Europe, which was constantly flooded with updates on Ukraine at all hours. Like others with close ties abroad, Nora has known about Russia’s propaganda tactics for years, and she knew that censorship was on the rise with the recent crackdowns. As she read reports on the atrocities in Ukraine, she became heavily invested and decided to take action—using dating apps to disseminate information.

“When I saw that there was a way you can directly impact how people perceive the war, who might not have access to the correct information—when you have the ability to make even just a small, tiny impact, I think it does make a difference,” she tells ELLE.com over Zoom.

When it comes to injustices in the world, a lot of young people, like Nora, feel inclined to get involved, utilize their resources, and try their best to help out. In fact, Nora is just one of the myriad individuals who’ve begun using apps like Hinge, Badoo, and Tinder to share news about the Russia-Ukraine war. Though she doesn’t speak Russian herself, her parents and friends do, which is how she was able to get her initial message translated into Russian in the first place.

Courtesy / Design Leah Romero

“People feel so helpless watching the scenes coming out of Ukraine, of all the refugees,” says Olga Lautman, a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis. “If you’re on dating apps, and you’re like, ‘Wait a minute, I have an idea. Let me work with that,’ that’s how you help.”

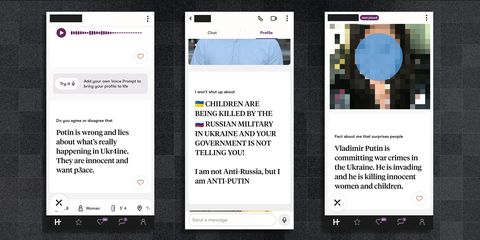

Some users added similar messages about the war directly to their profiles in English or Russian. In an Instagram post, Lithuanian influencer and Tinder ambassador Agnė Kulitaitė urged women to hop on this information-sharing trend, writing that they could “help humanity by spreading the truth.”

“Hopefully, the Russian people you match with will read your profile and become aware of what their leader is doing,” Kulitaitė wrote to her 88,900 followers.

A Hinge user named Maria included photos of ruins in Kyiv alongside an English language news excerpt. Svetlana wrote that Vladimir Putin is “invading and killing innocent children.” A user named Elle wrote about the country’s heavy censorship.

Swipe right. Swipe left. A new profile proclaiming the truth about Putin populates.

Why turn to a dating app in the first place to get these messages across? Many saythey felt compelled to take action in light of Russia’s strict censorship and fake news laws. The government instructed citizens to refer to the Russian invasion as a “,” or else face imprisonment for up to 15 years. On top of this, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter are currently banned or blocked in the country, with the Kremlin arguing that Facebook allows extremist activities to occur. Bumble Inc. has removed Bumble and Badoo from app stores in Russia and Belarus, but some can still access Badoo if the app is already installed.

“Young people here understand what is going on because we aren’t stupid,” a dating app user based in Russia wrote to a 25-year-old named Glen on the platform. “We don’t wake [up] in the morning, turn on the TV, and listen to everything they say.”

Glen, who’s based in Indianapolis, Indiana, downloaded Hinge specifically because the app allows users to change their location for free, unlike Tinder or Bumble, which require them to pay for premium accounts or find a workaround. This allowed him access to a wider geographic pool of people.

Courtesy / Design Leah Romero

Besides sharing factual information, dozens have also used Tinder to gather intel and triangulate the locations of Russian soldiers in Ukraine. To maintain their anonymity, those involved in gathering this type of data often use photos of people that don’t exist, with the help of random face generators or Photoshop.

Marijn Markus, a data scientist based in Rotterdam, Netherlands, created 10 burner accounts to implement what he calls “professional catfishing.” Because he doesn’t speak Russian, he used Google Translate to communicate with matches, often pretending he was a blonde female exchange student.

“A lot of people feel very helpless in this situation, demanding their politicians do something, but they don’t know what to do directly,” he says. “Some of them start painting flower art and selling that, which is good; but as a data person, I grab a beer and spend the night flirting with Russians.”

Markus’s sophisticated catfishing method started picking up speed in the past month, during which he shared links, screenshots, and information via Discord, Telegram, and multiple Reddit posts.

“We post saying, ‘Hey, I matched with Igor, and somebody else goes like, ‘Hey, I also found Igor, but he was just 20 miles from me,’” he says. “And in that moment you know Igor is 20 miles from Belgorod and 10 miles from Gomel, then you can correlate where across the border he is. If you do that 100 or 1,000 times, you find ‘Igors’ all across the border.”

Though Markus isn’t involved in analyzing the data himself, he gathers intel and shares it with others. “This is data on a fish, but if you have data on a lot of fish, you know how the oceans move,” he adds.

Another user named Alba reported 60 accounts to Ukraine’s IT Army and the official “Stop Russian War” bot on Telegram, which allows those using its messaging service to directly report activity to the Security Service of Ukraine.

“It’s interesting to participate in, probably, the first IT war,” the 22-year-old biotech student says. “When they announced the creation of a volunteer international IT army, I was totally into it. I spoofed my location to Belgorod, a Russian city near the Ukrainian border, where there were rumors of a high concentration of Russian troops. They were not wrong.”

Those who set their dating app location to Ukraine have used the app to donate funds, provide housing to refugees, and serve as someone Ukrainians can confide in during this challenging time.

“People are finding ways to use these platforms that are not for the intended purposes, but for positive change,” says Jess Terry, a disinformation intelligence analyst at Blackbird.AI. Adds Lindsey Metselaar, founder of the popular dating podcast We Met At Acme: “I’ve seen dating app success with hookups, relationships, and marriages, but the fact that users are expanding beyond romantic connections to looking after one another just goes to show how truly necessary they are. It’s really genius of people to think outside the box and use them in a different way.”

In the past, people used dating apps to show their support for BLM or joke about ending capitalism and “eating the rich.” Back when rioters stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6 of last year, a man on Bumble bragged about being part of the infamous incident. A woman on the app replied, “We are not a match,” before handing over screenshots to the FBI.

“All these efforts are really important because there are many platforms, there are many people—144 million people in Russia,” says Eto Buziashvili, a researcher at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab. “There is still a chance of impact.”

Courtesy / Design Leah Romero

Though Nora, Glen, and others on dating apps have made it a goal to share truthful information with people in Russia, they are sure to note that, of course, plenty have been dismissive of their attempts.

“Good luck with your propaganda,” one Tinder user wrote back to Nora. “The Russian people remember what Nazism is and will eradicate any of its manifestations. Putin is a great president.”

Even so, she and others, like Vanessa, a 36-year-old American with Russian ancestry on her father’s side, see the value in sharing the truth. Vanessa turned to the apps when she realized Russian citizens were being lied to.

“I know my profile has been seen, and that, for me, made what I did worthwhile,” Vanessa, who’s based in Sacramento, California, says. “With state-run media in Russia telling citizens only what they want them to know, it creates the likeness of a child having only the beliefs of their parents. It’s important to form your own opinions through exposure to multiple sides—even if it’s uncomfortable.”

It’s this type of persistence and repetition, Lautman emphasizes, that creates change.

“It’s always worth it to get the truth because, even if people don’t believe something today, eventually, it will prevail,” Lautman says. “If, today, [Russian citizens] see a warning via a dating app, and they’re like, ‘Oh, this is garbage. This is propaganda.’ And then in a week, they hear a friend say, ‘My son died, and, you know, he sent me this video of bombing,’ then that starts reinforcing the outreach.”

For now, dating app users like Nora continue to explore new and unconventional ways to help Ukraine. Some have even written “fake” Google reviews to share truths about Putin’s ambitions. One reviewer wrote, “The food was great! Unfortunately, Putin spoiled our appetites by invading Ukraine.” Both Google and TripAdvisor have since disabled reviews in Russia and Ukraine. Still, they say their endeavors to share accurate information—one match at a time—were well worth the risk.

“The truth can go a really long way,” Nora says.

Amanda Florian Amanda Florian is an independent journalist, filmmaker, and entertainer based between the U.S.

Read The Full Article Here