This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

TW: disordered eating, depression

I have always been a reader who prefers epics that are published in volumes and look a lot like bricks. It is one of the only aspects of my life in which I prefer the journey over the destination, and if a series has either a dragon or an “adventurer” on the cover and “volume 1” on the spine, it is guaranteed that I will at least give it a go. In general, I will automatically swipe left on anthologies or short story collections unless my BFF is published in them (shout out to S.W. Sondheimer’s work in Three Time Travelers Walk Into… because that story was GREAT).

I recognize that my preference for episodic fiction means that I am missing out on a lot of truly incredible writing, but as I realized when I was 6, I won’t have time to read all the books ever written unless science does some really spiffy things very quickly. This realization led to the first complete and utter meltdown I can recall experiencing; I refused to do anything but read for several weeks between kindergarten and first grade in an attempt to get “ahead of time.” My poor mother.

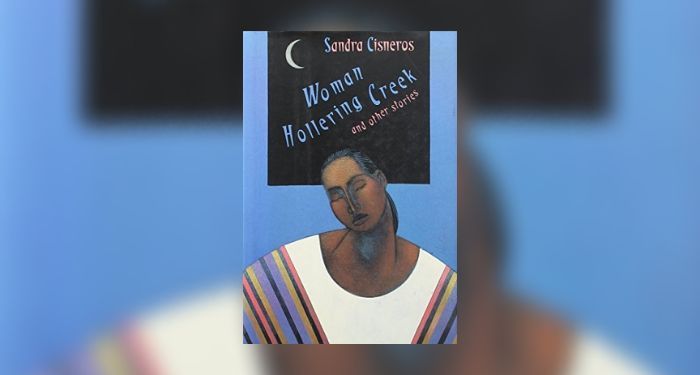

I don’t remember the first time I read Woman Hollering Creek: and Other Stories by celebrated author and national treasure Sandra Cisneros. It may have been high school. I know for sure that I read it in a college course, probably at community college in the mid-aughts, and as a result, a copy lived in my trunk until I got a new car in 2018.

My memory of the book itself is rather hazy. It feels hot and dry and tan — not beige, which is boring, but spending-all-summer-outside tan — and full of the smell of flowers and tortillas and kid sweat. Full of capital-F Feelings. Cisneros has a way of capturing emotion that leaves me floored, and despite being a slim volume of intertwined stories that last only a few pages each, it is heavy with meaning.

Today In Books Newsletter

Sign up to Today In Books to receive daily news and miscellany from the world of books.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox.

By signing up you agree to our terms of use

Woman Hollering Creek contains a short story called “Eleven,” in which it is Rachel’s eleventh birthday and should be a joyous day full of excitement and congratulations. She begins by reflecting on all the Rachels inside of her still: she is also still ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, and one. But she wishes she was one hundred and two, because if she were, she’d have known what to say when her teacher insists that an ugly, red, unclaimed sweater belongs to her and makes her wear it. Rachel’s inner birthday girls take over; her four-year-old self tells Mrs. Price the sweater isn’t hers in a tiny voice. Her three-year-old self feels sick inside. All of her — all eleven of her — push at the backs of her eyes and make them hot and prickly while she tries not to cry.

It is not an exaggeration when I say this story not only changed, but saved my life. It felt like everything I had been pushing away, down, and out for so long suddenly peeled away into their own selves, leaving me as more of me and less of a disaster. I began to see myself as a conglomeration of everyone I have ever been, with my “me” as the most present. When I said something utterly ridiculous in public, there was 10-year-old me awkwardly trying to make friends at a new school. When I got scared of my abusive parent and tried desperately to placate them even though I was long out of the house, my 16-year-old self was driving the Bus of Us; it is noteworthy in this example that I didn’t get my license until I was 17.

Fast forward a little to when I completely and totally lost my shit in 2012. Post-breakup, my 15-year-old anorexic took over and I stopped eating solid food for six months. I dropped 40 pounds and I couldn’t stop crying; I was simultaneously 15 and a toddler in full melt. My best friend finally convinced me to go to therapy — bless her forever — and it was with Evelyn I learned about a therapeutic modality called Internal Family Systems (IFS). She told me I had effectively been practicing “parts therapy” by allowing my bits and pieces to split off, and IFS could provide a framework to better support and therefore manage my parts.

IFS was developed by Richard C. Schwartz, author of many books on the subject including Introduction to the Internal Family Systems Model, and who founded the institute linked above in 2000. The book my therapist recommended is Self-Therapy by Jay Earley, who seeks to teach people to use IFS in a way that allows people to eventually “therapize” (my word) themselves. In the last decade, this has become more and more prominent in psychotherapy. It’s often called “parts therapy,” and I have given away at least one copy of Self-Therapy every year since I read it for the first time. Disclaimer: the following is my understanding, and I am not IFS trained. It can be different for everyone, but here is the basic idea: we each are a true Self with a capital S. And we also contain proverbial multitudes, many of whom separate themselves in order to keep the Self from experiencing a trauma or difficulty over and over again, or to allow the Self to continue surviving a difficult situation. Some of them live quietly for years — like my teen anorexic part did — until a situation occurs that causes them to activate and take over. Her goal was not to sabotage or hurt me; her goal was to protect me by taking control over the one thing she knew she could do: decide whether or not something went into my mouth.

“Eleven” is, from my perspective, the story of Rachel’s internal family coming together to express their collective hurt over an injustice. All of her parts did what they could to protect her from the kind of embarrassment only a child can feel. Rachel’s story allowed me to translate the weight and confusion of behaviors I was exhibiting, but didn’t understand, into a community of voices inside my head that I could learn from, guide, and relate to. My anorexic and I still struggle sometimes, but instead of screaming “WHY?!?” at my brain, I have learned to thank her for her protective instincts and usher her gently back to living in the background of my mind.

Whether or not you choose to look into IFS for yourself, I hope this story — both mine and Rachel’s — allows you to view yourself and any “shoulds” living inside of you with a bit more compassion. With apologies to the inimitable Ru Paul:

After all, if you can’t love your selves, how in the hell you gonna love somebody else, can I get an amen?