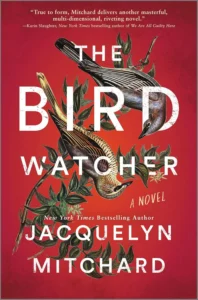

I’ve been reading crime fiction and true crime since adolescence, like many readers, maybe especially women. But until last year, I’d never written a crime novel. The Birdwatcher is about the trial of a very unusual young woman accused of a very unusual double murder, and about a lifelong friendship against terrible odds. It got me thinking obsessively about stories of someone wrongly convicted.

never written a crime novel. The Birdwatcher is about the trial of a very unusual young woman accused of a very unusual double murder, and about a lifelong friendship against terrible odds. It got me thinking obsessively about stories of someone wrongly convicted.

These stories emphasize the truth that justice is fraught and fragile.

Perhaps the most venerable is Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, the story of a Black man accused of raping a white woman in the racially volatile American South of the early 1930s, and before this classic came Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time, in which a bored Scotland Yard inspector pondering the enduring mystery of Richard III, who either did or did not murder the little boys who were heirs to the throne in the England of the 1500s. In The Count of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas told of a vengeful man framed by his friends, and even in Genesis (author unknown) was the story of Joseph’s wrongful conviction for rape.

In more recent years came Tayari Jones’s masterful novel of a couple torn apart by the husband’s wrongful conviction, An American Marriage, and Atonement by Ian McEwan, as well as one of my favorites, Dark Places, Gillian Flynn’s tale of a woman who has come to doubt the evidence she gave against her brother when he was tried for killing their family.

I thought again about all these stories as I wrote, and still I was left with a question: are people more offended when the guilty get away or when the innocent got punished undeservedly?

I spoke with Scott Turow, maestro of contemporary crime fiction, (Presumed Innocent, among many others, the unforgettable story of a lawyer charged with murdering the colleague with whom he had an affair). Despite an astonishing career as an author, Scott remains a defense lawyer. Many years ago, he worked on innocence cases with Larry Marshall of Northwestern Law School, probably the person most responsible for the repeal of the death penalty in Illinois. At that time, Larry Marshall wanted to focus mainly on innocence cases, which, although there are too many, are far rarer than the many death-penalty cases that have serious flaws.

Larry Marshall thought the innocence cases would better mobilize public opinion – the other death-penalty cases seeming to be “guilty scumbags looking for legal loopholes.” Scott objected that there was so much more wrong with the whole system of the death penalty. In intervening years, however, Scott says he has realized that Larry Marshall was entirely right: what Americans care about most of all in this context is making sure that innocent people are not put to death.

In 2003 when Illinois Hello Governor George Ryan declared a moratorium on executions, at least 17 people on Death Row were later exonerated. That small percentage, Scott told me, was enough to make people uncomfortable even though the other 90% were not innocent. Scott says his enduring belief is that in the minds of most Americans convicting an innocent person is the gravest injustice, outranked of course by putting an innocent person to death.

More than 50 countries still practice the death penalty. It’s most common and most covert in China, less hidden in places as Iran and Saudi Arabia, and in some places, among them Israel and Japan, reserved for multiple murders, kidnapping or war crimes.

Some countries still have the laws but have not used them in more than ten years.

The only countries that have the death penalty for so-called “ordinary” crimes are Tawain, Singapore, and the United States. The death penalty is used in only 16 states, with Texas posting the largest number of executions. Still, an execution is rare, relative the ponderous system it requires (although the same pertains to a tornado shelter in Oklahoma). The process drags on for years, raising the question of whether the condemned, is, at 35, the person he was when he was 19? Never mind the other thorny issues, such as the death penalty’s apparent failure as a deterrent.

Crime-fiction queen Karin Slaughter once told me she might be okay with the death penalty if there was zero percent of a mistake. But no system with human beings running it is fail-safe, so the of a wrongful death to punish a wrongful death is still an uneasy possibility.

The anguish of a loved one being killed is all-consuming. A woman whose daughter had been brutally murdered told me once that the perpetrator’s execution did give her a moment of triumph. But it was, she added, only a moment. And nothing else was changed.

Jacquelyn Mitchard’s newest novel The Birdwatcher, was published in December by HarperCollins.