At a time when women’s rights are once again threatened, it’s worth looking back at what feminist authors warned us about decades ago. When Margaret Atwood published The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985, she was part of a powerful wave of women writing feminist dystopian science fiction, which we now call speculative fiction.

The late 20th century was rich with feminist parables, many bleak and some urgent, penned no more than 50-60 years after women first achieved voting rights. For female writers who had just earned the right to own property in their own name or use contraception, the struggle for suffrage and equality was still crucial.

These novels deserve to be read again, not just as relics but as resonant, provocative mirrors. Some remain startlingly relevant, others reveal their age, but all are ripe for rediscovery by a generation facing distressingly familiar battles.

The Female Man by Joanna Russ (1975)

Long before alternate realities became a staple in science fiction, Russ took readers on a trip to four different parallel realities — a world like the contemporary 1970s, a world where the Great Depression never ended and the feminist movement never developed, a crime-free agrarian world with no men, and a world where men and women live in separate nations constantly at war. Joanna, the woman from the contemporary time period, travels with her alternate selves to these other realities, learning from each other’s experiences and seeking ways to inspire a better future.

Woman on the Edge of Time by Marge Piercy (1976)

This visionary novel was my personal favorite during my college years. It follows a young Latina who has rebelled against the system. She finds herself confronted with two possible futures and must figure out how to create the one that would be healthiest for her unborn daughter. One future has ideas that are so current that it’s hard to believe it was published the same year as the election of Jimmy Carter and the Bicentennial. Filled with fervent hope and clarifying anger, Woman on the Edge of Time is an unblinking look at what it takes to survive the patriarchy.

Native Tongue by Suzette Haden Elgin (1984)

One of the truly fascinating things about Native Tongue is that it began as a thought experiment. Elgin wanted to see if women would embrace a newly constructed language that more precisely mirrored their thoughts and feelings. Sadly, unlike Star Trek’s Klingon, Elgin’s newly constructed language, Láadon, failed to gain interest despite her best efforts. But it plays a pivotal role in a dystopian future where the 19th Amendment has been repealed, and women have no civil rights.

Nazareth is a gifted linguist, part of a small band of people who have been carefully bred to be perfect interstellar translators to alien races. All she has to look forward to is being retired to Barren House, the hostel where women who are no longer of use as breeders live out their last years. It is there that Nazareth discovers that the elderly women have been creating their own language as an act of rebellion to help free them from the patriarchy.

Long before Amy Adams played a xenolinguist in the 2016 movie Arrival, which suggested that language can shape perception and reality, Native Tongue explored those themes. It’s a fascinating look at how major acts of rebellion can start with tiny changes, and how language shapes how we see the world.

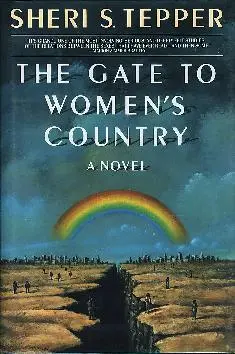

The Gate to Women’s Country by Sheri S. Tepper (1988)

The choices we make in service to controlling our world come under scrutiny in this post-apocalyptic civilization, where most women and men live in separate communities. The women lead lives of intense scholarship in Marthatown, where the only males are children and servants bonded to the extended families of women. The rest of the men live in the garrison as warriors, only coming into contact with women once a year for a sort of futuristic bacchanalia — their reward for lives devoted to training and fighting garrisons from other small cities.

Stavia, a young doctor, is sent south on a journey of exploration and is captured by a brutal fundamentalist patriarchy and incapacitated. Her escape and return to Marthatown raise questions about the nature of the society she takes for granted, and the extremes the city mothers will invoke to protect themselves from patriarchal control.