This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

In recent years, mainstream comics publishers like DC and Marvel have made great strides in increasing the LGBTQ+ rep in their universes, though they still have a long way to go. But getting here was a slow and gradual process, with many notable landmarks — and some admitted missteps — along the way. In Queer Superhero History, we’ll look at queer characters in mainstream superhero comics, in (roughly) chronological order, to see how the landscape of LGBTQ+ rep in the genre has changed over time. Today we’ll be looking at the earliest explicitly trans characters in comics: Wanda Mann, Shvaughn Erin, and Coagula!

Content warning:The stories discussed below include fictional transphobia, transphobic tropes, and potentially outdated or offensive language.

As I mentioned when I covered the Marvel character Cloud, comics have long had a history of stories involving changing genders…but via science fiction or magical means. Even Cloud, despite canonically identifying as nonbinary now, is a sentient nebula and thus their nonbinary, genderfluid nature could be dismissed back in the ’80s as a fantastical comic book story and not anything that could be applied to the real world.

But the characters I want to talk about today don’t fall into that category. From 1991-1993, DC introduced three trans women in three different comics. They still live in an outlandish comic book world, but their being trans (mostly) has nothing to do with that. Some are handled more gracefully than others, and they are all fairly obscure characters — but they’re also all groundbreaking in their own way.

Wanda Mann

The Sandman, written by Neil Gaiman and drawn by a variety of artists from 1989-1996, is sort of a borderline case when it comes to talking about mainstream comics. It was published by DC (though as part of their Vertigo imprint from #47 on), and though it technically takes place in the DCU, or at least a version of it, it is distinctly not a superhero comic. Still, it is a Big Two comic, and one of the most influential ones of all time at that.

The Stack Newsletter

Sign up to The Stack to receive Book Riot Comic’s best posts, picked for you.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox.

By signing up you agree to our terms of use

Sandman had always included incidental queer characters, but the storyline “A Game of You” (issues #32-37, beginning in November 1991 and drawn by Shawn McManus) introduced three major queer characters: lesbian couple Foxglove and Hazel, and trans woman Wanda Mann, who is close friends with the story’s protagonist, Barbie. When Barbie’s mind is pulled in to rescue a fantasy realm she used to dream about as a child, her cis female neighbors (Foxglove, Hazel, and a witch named Thessaly) follow her to rescue her, while Wanda remains behind to protect Barbie’s body. However, the powerful magic involved summons a hurricane, which causes the building Wanda is in to collapse, killing her. In the final issue of the story, Barbie attends Wanda’s funeral, where she meets Wanda’s conservative, bigoted family, who bury Wanda under her deadname. Barbie crosses out the deadname on the headstone with Wanda’s favorite lipstick and writes “Wanda” instead.

I did some editing to remove the fairly graphic images of the, um, dead disembodied human face Wanda is talking to. Sandman is a horror comic, folks!

I did some editing to remove the fairly graphic images of the, um, dead disembodied human face Wanda is talking to. Sandman is a horror comic, folks!

Just from that short paragraph, it’s clear that there are a number of problematic elements here. Giving Wanda the surname Mann (her birth name, not one she chose) feels like a tasteless joke now. She’s repeatedly misgendered throughout the story, particularly by Thessaly, who insists that only characters who can menstruate can travel to the dream world and by the Moon, who also excludes Wanda from Thessaly’s spell. She’s literally misgendered by word of god (though it’s worth pointing out that gods in Sandman are deeply fallible). And of course, Wanda dies — the only major character in the story to do so — and the reader is then subjected to a barrage of transphobic hate from her family to close out the arc.

That said, Wanda is compassionate, brave, witty, and deeply likable. She’s also fierce in her insistence that she knows who she is, even when terrified and completely out of her depth. And of course, she was the very first trans character to appear in a mainstream comic ever, and one written with sympathy and very obvious good intentions, while her transphobic family is roundly condemned.

In this article about trans rep in Sandman, Joanna Marsh goes into depth about the problems with how Wanda is written, but then adds:

“I think of the history where there were no trans characters before Wanda in mainstream comics beyond subtext, allegory, and body swaps. I think of people for whom Wanda was their first known experience seeing a trans person and how it would have had to be dropped on heads like a house in a hurricane that she was a real person and a real woman and a real hero. In a time where the luckiest of us were talk show sideshows, this was practically veneration.”

For his part, Gaiman has said many times that he would write Wanda differently if he were to write the story now, and that if the Netflix adaptation reaches “A Game of You,” there will be trans writers involved. The audio adaptation cast a trans actor, Reece Lyons, to play Wanda.

Shvaughn Erin

The Legion of Super-Heroes is a long-running DC team of young heroes from the 30th-31st century. Shvaughn Erin was first introduced in Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes #241 (July 1978) and was created by Paul Levitz and Jim Sherman. She is a member of the Science Police and an ally of the Legion in Commissioner Gordon/Maggie Sawyer fashion, and she’s (arguably) the first trans character in the main DC universe, though she was not initially presented as trans.

Shvaughn was a regular but minor character for years, eventually developing a romantic relationship with Jan Arrah, AKA Element Lad. This didn’t go over well with some fans, who had long read Jan as gay. In fact, as early as 1976 — 12 years before DC’s first out gay character — a fan asked if he was gay during a DC panel at a con. The question was not answered, but DC continued to leave Jan single and ambiguous, perhaps in deference to queer fans. Even Jim Shooter, longtime Legion writer before he became EiC at Marvel, said in a fanzine that he assumed Jan was gay (though given Shooter’s track record, it’s probably best that he never put it in the actual comics). So Paul Levitz giving Jan a girlfriend was not well received by queer readers.

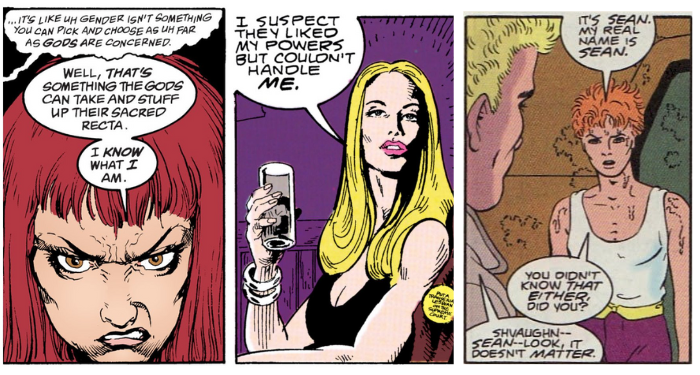

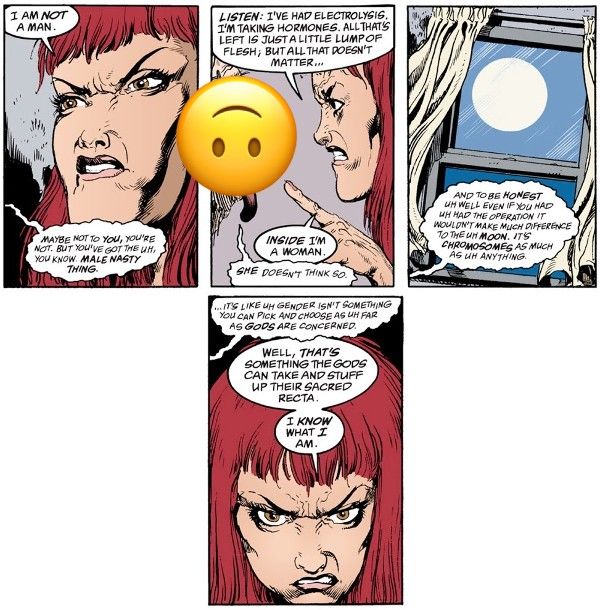

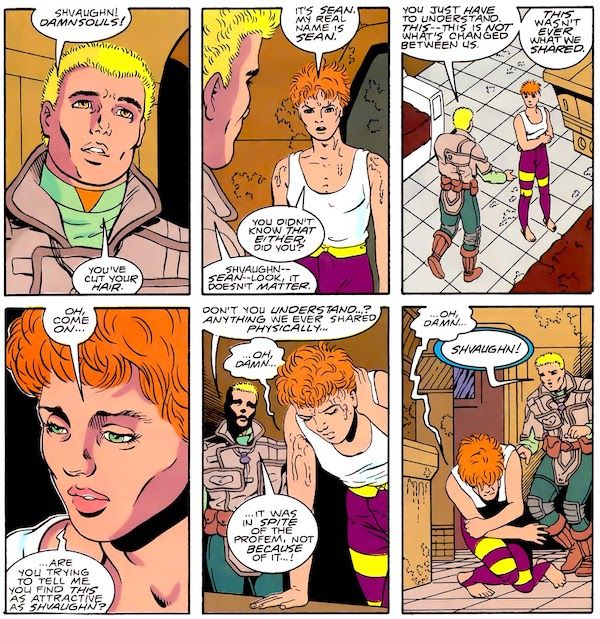

This was, um, “fixed” in Legion of Super-Heroes #31 (July 1992), written by Keith Giffen, Tom Bierbaum, and Mary Bierbaum and drawn by Curt Swan and Colleen Doran. During this story, Earth has been taken over by the alien Dominators. The occupation means that it’s impossible to get certain medications — which is when it’s revealed that Shvaughn was born Sean Erin, and has been taking a drug called Profem to transition. With the drug running out, she detransitions — a process that is painful both physically and psychologically.

Jan, I don’t think that’s helpful.

Jan, I don’t think that’s helpful.

Jan insists that he doesn’t care, even heavily implying that he would have preferred Shvaughn to have been a man all along, which is…probably less reassuring than the writers think it is. The characters then go their separate ways. Shvaughn only appears twice more in that continuity and continues to go by Sean and he/him pronouns. In his last appearance as Sean, however, he rushes to Jan’s bedside when Jan is close to death and agrees to nurse him back to health, with the implication that the two are getting back together.

Legion continuity was rebooted shortly after this, wiping out Jan’s history with Shvaughn/Sean. Post-reboot, Shvaughn goes by she/her pronouns, though whether or not she is trans is never addressed. Meanwhile, Jan was rebooted back to being a teenager, while Shvaughn is an adult, so their romantic relationship has not resumed.

Shvaughn as Sean.

Shvaughn as Sean.

Like Wanda’s, Shvaughn’s story is well-intentioned but deeply problematic. It seems to be far more interested in heavily implying Jan’s queerness — the language both characters use to talk about Jan’s desires and identity is very loaded — to the detriment of considering what any of this means for Shvaughn. Charlotte Finn argues that Shvaughn is depicted not as trans, but as a cis gay man who transitions solely to pursue a relationship that would be forbidden by his culture of origin otherwise, and also highlights the writers’ use of the “trans character as inherently deceitful” trope.

Shvaughn hasn’t been seen in some time, and Jan is still not technically canonically queer — in fact, a later continuity gave him a crush on a female character. The Legion doesn’t currently have a book, but the next time they do, DC is long overdue to let Jan be canonically queer and Shvaughn be canonically, unequivocally trans, whether or not they’re together.

Coagula

Kate Godwin, AKA Coagula, bears two important distinctions: she is DC’s first trans superhero (Wanda and Shvaughn are civilians), and, unlike the other characters in this article, she was created by a trans writer: Rachel Pollack.

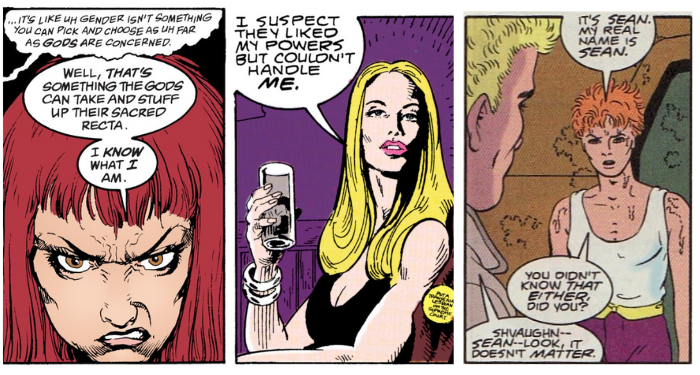

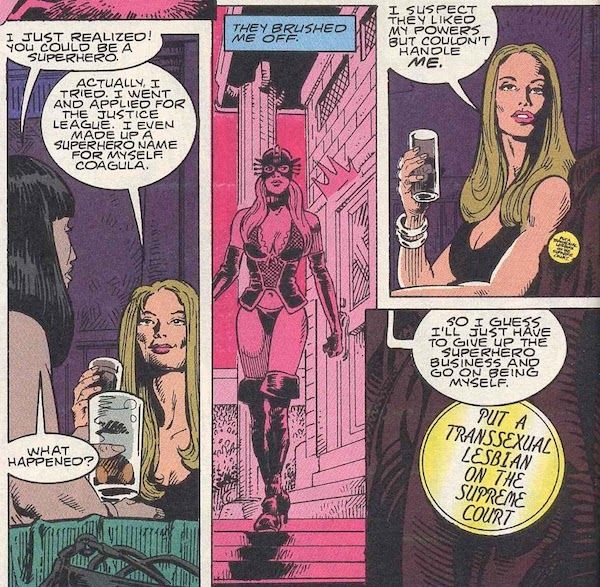

Kate first appeared in Doom Patrol #70 (September 1993), drawn by Scot Eaton. She’s a computer programmer and former sex worker who has the ability to dissolve substances with one hand and solidify — coagulate — them with the other. She tries to join the Justice League, but as she puts it, “I suspect they liked my powers but couldn’t handle me.” But when she helps the Doom Patrol defeat the two-bit villain Codpiece (yes, really), they invite her to join and she accepts.

The button on Kate’s coat uses what was preferred terminology at the time.

The button on Kate’s coat uses what was preferred terminology at the time.

Since its debut in the ’60s, the Doom Patrol had always been a team made up of misfits and outcasts, or as Pollack put it, “people that had problems with their bodies.” A team that included a human brain in a robot body and a genderless energy being fused with both a mortal man and a mortal woman was ideal for exploring themes of gender, identity, and dysphoria.

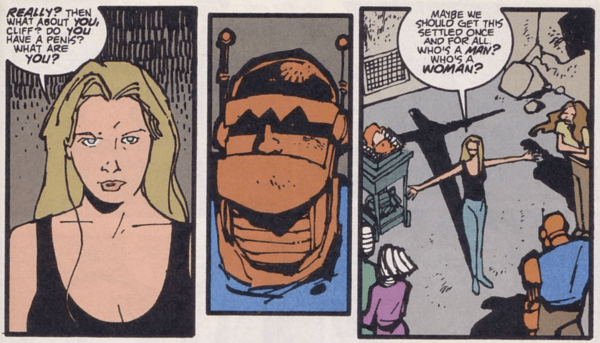

Unlike Wanda and Shvaughn in their supporting roles, Kate played a central role for much of her time on the Doom Patrol. She grows particularly close with her teammate Cliff “Robotman” Steele (the aforementioned human brain in a robot body, and trust me when I say that’s the simplified explanation), who is attracted to her and is upset when he learns she’s trans. “I was never a man,” she tells him. “What about you, Cliff? Do you have a penis? What are you?”

As a cis woman, it’s not my place to say which portrayal of a trans character is “best” out of the three covered here, but to my eyes, Kate’s is the most nuanced. Though Doom Patrol does address misgendering, dysphoria, bullying, and both subtle and overt transphobia, it doesn’t go for shock value the way Sandman does — and Pollack clearly knows she’s writing a trans character, which the Legion writers maybe didn’t. Pollack, who sadly passed away in April of this year, said that they received “some very positive letters” about Kate, “including one or two letters from people who quite simply said their lives were saved by this. [That] it kept them from killing themselves, this character.”

Doom Patrol was canceled in 1995, and Kate didn’t appear again until 2002, when she was immediately killed off. However, she did have two blink-and-you’ll-miss-’em cameos in DC’s 2022 Pride anthology, so it’s safe to assume that like most superheroes, her death was only temporary. Hopefully that means she’ll be back for more than a fleeting cameo soon.

From today’s perspective, the early ’90s feel like a key tipping point for queer rep, where mainstream comics went from just two queer characters of note to almost a dozen — not enough by any means, but a significant and positive increase.

Our current moment feels like another tipping point, particularly for trans rep. In recent years, DC and Marvel have debuted a number of trans characters, from civilians (Alysia Yeoh, Dr. Victoria October) to superheros (Dreamer, Escapade, the brand-new Circuit Breaker). Again, I wouldn’t by any means say that they have a lot, but the fact that there are too many for me to list them all succinctly is a sign of how very different the comic world is today than it was 30 years ago.

The characters profiled above aren’t without flaws. While I found a number of essays from trans comic book fans about how deeply meaningful Coagula was and remains, there are just as many unpacking the harmful tropes in Wanda and Shvaughn’s stories — which just speaks to the importance of own voices storytelling. (Another area where DC and Marvel have improved significantly but still have a ways to go.)

But those same essays spoke about how important it is just to be seen, even if it’s an imperfect portrayal. Wanda Mann is a deeply flawed portrayal of a trans woman, but she’s also a sympathetic portrayal in one of the bestselling series of all time. And flawed portrayals can help pave the way for better and more authentic ones. Too often new marginalized characters are presented as the first of their kind — googling Alysia Yeoh, for example, will get you many articles about how her coming out in 2013 made her the first trans character in comics. But celebrating the new shouldn’t mean erasing history, because that history mattered to readers.

In a time when trans rights are under concerted attack in the U.S. and many other countries, it’s important that we continue to see more trans heroes in mainstream comics, and that trans writers are given the platform to tell their own stories. Everyone deserves to see themselves in stories, and everyone deserves a chance to be the hero. So let’s celebrate the newcomers to the DC and Marvel universes — but let’s remember the ones who paved the way, too, if only to see how far we’ve come.