I grew up in a family of secrets that I wasn’t supposed to reveal. Of course, because they made such great stories, I did anyway, but I did it in fiction, writing about my parents, my sister, always changing their names, their appearances. “It’s no one’s business what goes on here,” my mother warned me.

My mother was Bea in my first novel, Meeting Rozzy Halfway, an unhappily married woman struggling to raise two very different daughters, and pining away her life for the man who jilted her when she was just 19. She never recognized herself in my books. My sister made an appearance as Charlotte in Cruel Beautiful World, one half of a troubled sibling relationship, but she never recognized herself either until during an NPR interview I blurted out that the anxious rule-following sister with an unsettled life was my sister.

My sister was furious.

I apologized, but I couldn’t stop writing about my family because the stories were so extraordinary to me. I needed to try to understand what had made my family members who they were — and why.

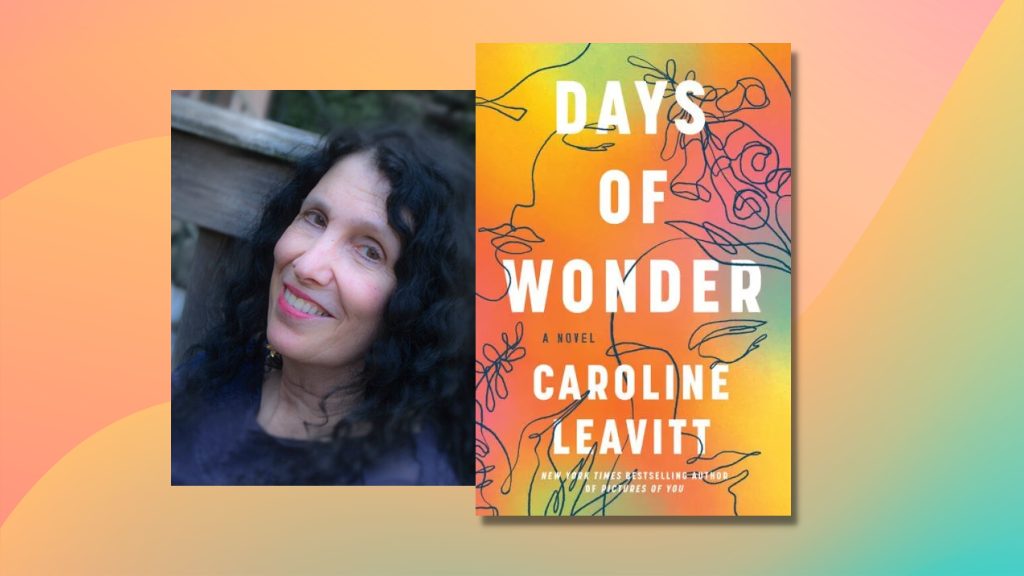

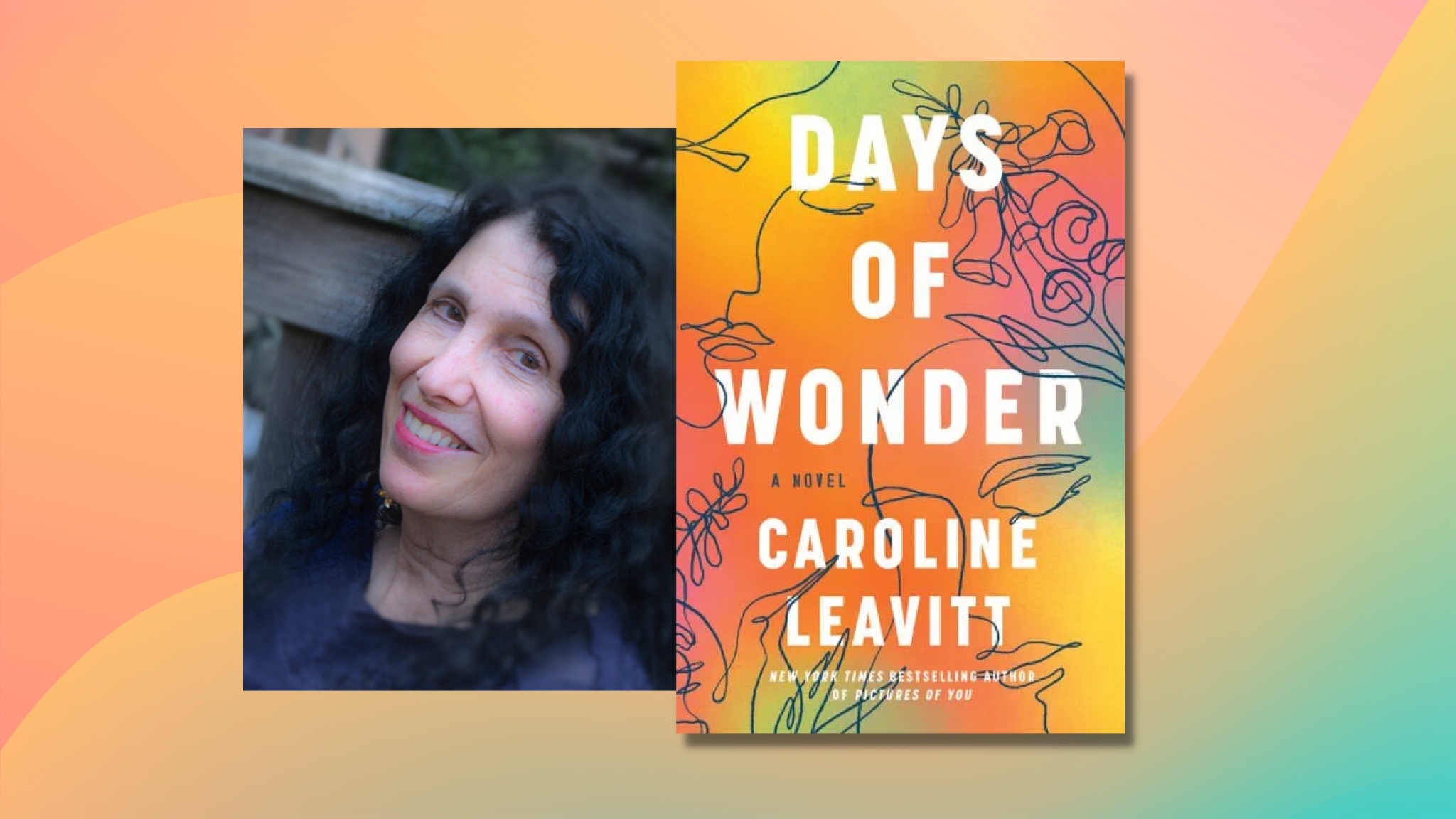

So why am I using ALL their real first names for the very first time in my very long career and over many books now in Days of Wonder (Algonquin Books)?

Many wonder…

Honestly?

It’s because it’s the first year that both my parents are dead, and my sister is fully estranged for five years now and wishes me dead. Buy I don’t just want to write my personal history via fiction. I want to revise my family’s lives and to do that, I needed to truly name names.

Shortly after my mother died, four years ago, I began to write Days of Wonder. I remembered all her stories about growing up Orthodox Jewish in an extremely tight-knit community, self-ousting herself when she was a teenager, and always being conflicted about who she was and where she belonged. I began to write her story, and, almost naturally, her name appeared on the page: Helen. It shocked me at first, but then it propelled me to keep using it, as if it were the next step to understanding and keeping my mom alive. Like my mom, fictional Helen left her religious community, but she wasn’t pushed out. Like my mom, my character raised a daughter alone. Like my mom, she agonized about guilt, something my character grappled with and resolved. The more I wrote, the more I felt my real mother around me, which comforted me. I loved making her life richer, better, deserved.

But if I named my character after my mom out of love for her, why I chose to name a character Henry, like my dad, was very different. My father was a sulky, silent brute of a man who didn’t just yell, he screamed, his face contorting. He bullied and used a belt for misbehaviors. When I was five, my father demanded that I sleep beside him. I didn’t want to. I kept my body stiff, away from him, and in the morning, he threw back the covers, and then I saw he was naked, and when I stared, he snapped, “You should be ashamed of yourself, looking at me.” He never touched me again, never said he loved me, never showed affection, and on the night of my very first kiss, he came out onto the porch in his underwear to threaten to call the cops on this boy for molesting his daughter.

So why name a character — a good man of the story — Henry? This time, I wasn’t revising my father’s life. I was instead attaching his name to a new identity. My Henry was nothing like my father. My novel Henry was kind, funny and soft-spoken. He never pushed anyone sexually or raged. It’s always bothered me that I could never forgive or understand my father, that I couldn’t find the distance I needed.

But because my character Henry was so good, so kind, so open — I no longer cringed in fear or anger when I wrote the name Henry or heard it spoken in my head. Instead of thinking of my father’s balled-up fists, I thought, instead, of the calm way my fictional Henry, a complete opposite, would lovingly sand a piece of wood.

I’ve written about my older sister Ruth in fiction before, always with a different name, different personality, and different appearance. She’s had an unhappy life — and worse, she feels as though I’ve stolen her life by having the things she so desperately wanted but refused to try for: a writing career, a home, love. But because she is still alive, I gave her only a few sentences, as Ruta, the Hebrew name for Ruth, a young orthodox Jewish girl who follows all rules and orders but who is in the exact right community to do so. And in my fictional world, Ruta has comfort, love and connection. What I hope for the real-life Ruth.

When I think of this book, I think of my family. My dead parents, my estranged sister, live in my novel in a kind of parallel life. In Days of Wonder, Helen makes peace with her Orthodox past in a way my mother never could. My father becomes a man who bears his name but none of his personality, which for me, redeems him in the only way I know how, and my sister in my book is a woman who can be comfortable in her own skin, even if just a few sentences.

I know I didn’t put their names in my book for them to read. I know, too, that I did it for me, so I could live another kind of life with them, keeping them alive in the best possible way.