Camp Independence and Responsibility and Camp Don’t-Wanna-Be-Here

Camp counseling was once a coveted gig in the teen world, if the fiction of the ’80s and ’90s is any indication. Books like the Camp Counselors series by Diana Ames played into the same romantic ideals that Nickelodeon shows like Hey Dude and Salute Your Shorts of the time did. Ames’s series offered tweens and teens the opportunity to imagine falling in love and breaking hearts. It harkened back to some of the camp books of the ’80s, including titles like Camp Girl-Meets-Boy by Caroline B. Cooney, and what made this era of YA camp books stand apart from earlier camp-themed series like the late-’80s Camp Sunnyside Friends by Marilyn Kaye was that teens were the ones in charge — not the ones being led.

Being a camp counselor, in addition to offering the opportunity for love, is indicative of maturity and independence. Where cars have always been symbolic of freedom, camp counseling offered an even broader arena of possibility: there is little adult oversight, there is money to be made, and it’s not always limited to the financial privilege of transportation.

Camp counseling, much like camp itself, is the adolescent experience in a microcosm. It’s time away from home, away from school, and away from everyone who knows you. Camp lets you enter a chrysalis, with the hope of emerging as a newer, better person at the end.

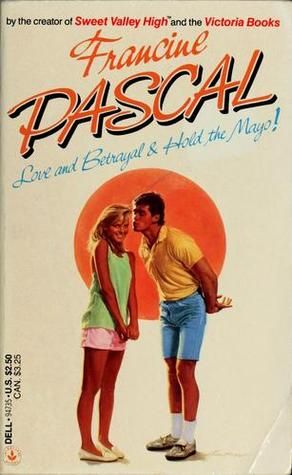

Not all of the camp jobs were as counselors, though. Francine Pascal entered the camp sphere with a story about Victoria in Love and Betrayal and Hold the Mayo, who works as a camp waitress 200 miles from home. She’s excited for the job, but it turns out the gig isn’t what she expected, and she might be falling for someone who is entirely unavailable.

Sometimes, the reasons teens took jobs at camp was because of their life experiences. Lurlene McDaniel, mother of the so-called “sick lit” category of fiction, did just this. Dawn, in So Much to Live For, is a two-time cancer survivor and agrees to take a job at the summer camp she and her best friend attended. She wants to be an inspiration for the younger campers who are struggling with their own health challenges. The problem is camp is not the same without her best friend who died.

For Marcy, the main character in Paula Danziger’s There’s a Bat in Bunk Five, being invited to be a counselor for a teacher’s creative arts camp seems like the perfect chance to let go of the shy and insecure girl she once was. It’s unfortunate, though, that the campers will be a challenge and more, that she can’t get rid of some of the fundamental parts of herself, even in a new setting. She’ll have to instead learn to embrace and honor who she is, as she is.

The summer camp experience changed quite a bit during the ’80s and ’90s, too. No longer were the stories primarily about adventure. Certainly, adventures happened, but now camp meant the possibility of not only love, but also death, betrayal, and other darkness.

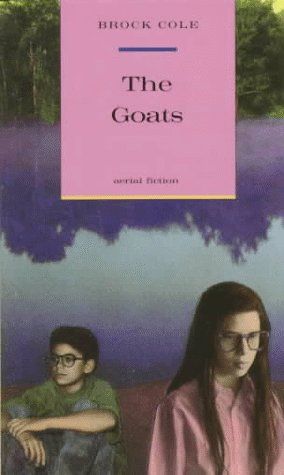

Brock Cole’s 1987 cult classic The Goats is an example of when camp goes wrong — very wrong. Following a boy and a girl who are stripped and sent to a small island by a group of campers who are participating in “just a tradition,” the two stranded teens are unable to get help. . . and maybe, as it turns out, they quite like life on their own. Another dark tale from the ’80s is Steven Kroll’s Breaking Camp, a The Chocolate War-esque story of cruel initiation.

Other camp stories in the ’80s and ’90s not as easy to connect thematically included Hail, Hail Camp Timberwood by Ellen Conford, about a teen who doesn’t want to be shipped off to summer camp and dreads being forced to be around such young kids, especially as she begins to fall for the cute guy. The Summer War by Harry W. Paige took a teen through a horrifying experience of discovering buried skeletons at a camp in the Adirondacks, and when the ’00s rolled around, things got supernatural at camp with Beth Goobie’s Before Wings.