Representing children’s authors and illustrators is a family business in our house. My mother started her own agency in the 90s, and long before I grew up and took it over, I used to read the submissions for her. In fact, I started as a teenager, so I suppose I’ve been reading them for close to thirty years. In all that time, here’s a consistent category I’ve noticed: stories about disability written by non-disabled people.

I’ve always taken an interest in these stories because I’m disabled myself: I have one leg. Now, I never really noticed an absence of people like me in published books I read. I had no trouble relating to all the two-legged heroes I read about. But I was struck by how these writers in our submissions — often parents of disabled children — did notice this absence. They would always refer to it in their letters: I want my child to see him or herself in a story, so I wrote one.

And that sounded good to me. Except… the stories never rang true. One that stuck in my mind, for obvious reasons, was called Tumbleweed, The One-Legged Hen. Whenever the wind blew, over Tumbleweed would tumble. So funny, so sad. Then his friends made him an artificial leg. No more tumbles.

I probably don’t need to emphasize how little I related to this singularly miserable chicken, laughed at and pitied and helped to her happy ending. The author’s intention may have been pure, but their efforts to spin a yarn out of a character they could not comprehend had taken them in some strange and troubling directions. But hold on, that’s an unpublished author, I hear you say. Disability stories by proper authors must be better? Well, I say: Tumbleweed is just Tiny Tim with feathers. And Tiny Tim still respawns endlessly, in almost every heartwarming story where a disabled child treads that familiar path from tragedy to triumph.

Thirty years on from Tumbleweed, an author-illustrator sent me a story about a one-legged teddy bear. Poor thing had Googled me just before clicking send, panicked a little upon realizing I was a one-legged agent, and then sent it anyway with a reassuring note that it WASN’T ABOUT ME. I told her I knew it wasn’t… and yet, albeit unintentionally, it kind of was: it was a story about disability whether she meant it or not. And like all the others I’d read by non-disabled authors, it didn’t ring true. But maybe, I said, I could try to write a new story for this character. And generously, she agreed.

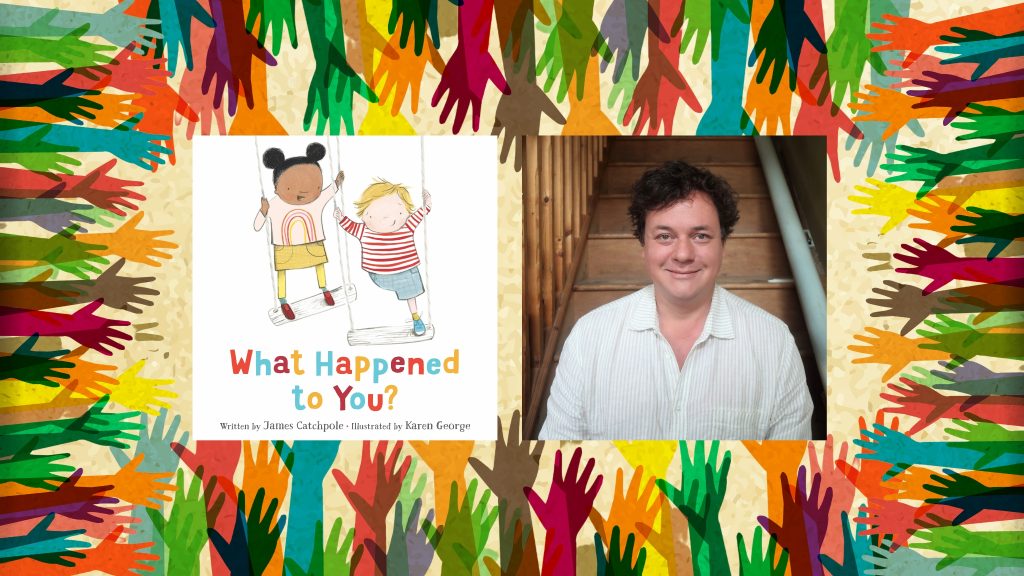

It took a while to get it right, but eventually the bear became a boy called Joe and the story became What Happened To You? by me, James Catchpole, illustrated by her, Karen George. And perhaps unexpectedly for a picture book about disability, it has been a success, selling handsomely back in the UK, being shortlisted for prizes and translated into several languages and picked up for the North American market by Little, Brown Books for Young Readers.

I like to think at least part of this must be because, unlike all those stories about disability by well-meaning non-disabled people, my story was able to put a disabled experience front and center and tell it like it truly is. And somehow, that’s still a revolutionary act.

Does that sound like hyperbole? Then consider this.

Being singled out by other kids in the playground and asked over and over again “what happened to you?” or “what’s wrong with you?” is perhaps the most difficult thing about having a visible disability — about looking different. And it still is for disabled adults, of whom other adults feel entitled to ask these questions all the time, whether at the bus stop or the grocery store. But what’s the cultural consensus on this issue, according to the bestselling non-visibly disabled picture-book writers? If in doubt, just ask. Because disabled people will be only too happy to tell you their trauma stories while buying milk. They’ll just be grateful you’re not staring at them or — God forbid — feeling awkward. And disabled kids? (Cue Tiny Tim voice…) Teachable Moments, Every One!

This is what happens when disabled stories are almost always told by non-disabled writers.

Now do you believe me, when I say that flipping this consensus, and telling a disabled child’s story from the inside, still feels revolutionary? I hope it won’t for much longer. Because these are the stories about disability that need to be told.