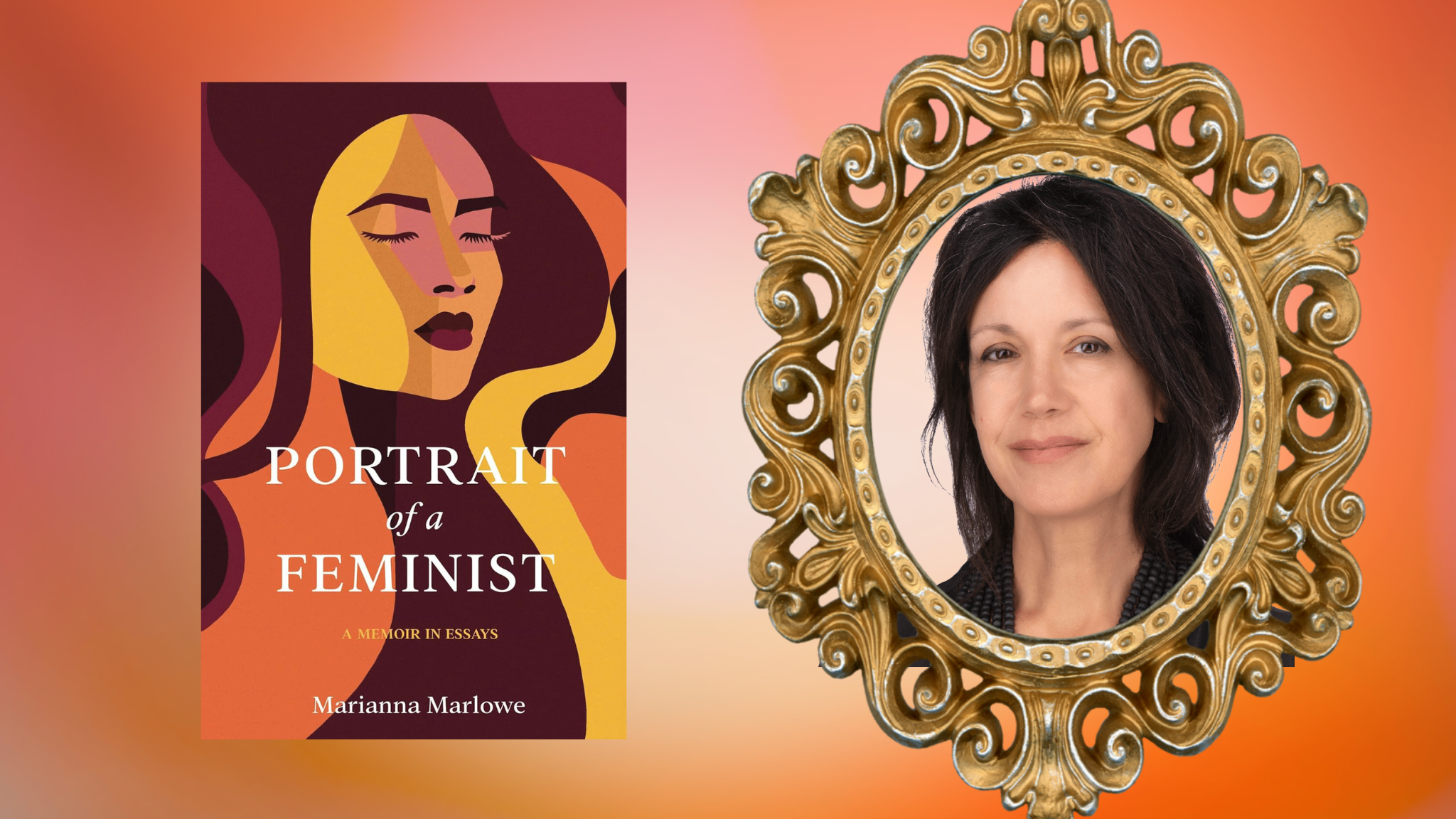

In Portrait of a Feminist, the author weaves personal narrative with cultural critique, offering a deeply reflective exploration of identity, gender, and selfhood shaped across multiple continents and belief systems.

In this Q&A, we talk with author Marianna Marlowe about the roots of her feminism, the complexities of family, faith, and love, and how her life experiences have informed a more fluid, inclusive vision of what it means to live a feminist life.

Portrait of a Feminist explores your upbringing across California, Peru, and Ecuador. How did living between these cultures shape your early understanding of gender roles and identity?

Living in different cultures helped me absorb, from an early age, the idea that gender is in many ways constructed. Even if subconsciously, I could not but notice how, for example, my Peruvian mother and grandmother defined ideal femininity as opposed to how my British grandmother defined it. Or why was it that in the United States certain colors were acceptable if not desirable—blacks and grays and maroons, for example—and in Lima or Quito they were considered plain and drab? Then again, when I went to graduate school in Seattle, I felt like I was too much—too bright, too lipsticked and nail polished, too long haired and designer dressed—compared to students who routinely wore fleece and Doc Martens.

On a deeper level, gender roles were more open and diverse in California than in Lima or Quito. Women were more overtly tracked into wife and motherhood in South America, while in the United States the fact that I would get a higher education was taken for granted, at least by my family and friends. On the other hand, I learned in university about the “second shift” that is so common for many North American women, yet it has remained largely invisible as unpaid domestic labor.

How did your mother’s Catholicism and your father’s atheism influence the way you approached questions of gender, faith, and autonomy as a child?

Growing up I identified with my mother way more than with my father; I was a “mommy’s girl.” In addition, I attended an Evangelical missionary middle school in Quito, reinforcing Christianity as the dominant discourse of my childhood. At my missionary school they stressed Protestant Christianity as the only path to salvation, so talking to my father about his “faith” and discovering he didn’t believe in God at all kickstarted years of worry about him. In general, however, I believed in a Catholic/Protestant blend of Christianity that only began to be challenged during my undergraduate years at UC Berkeley.

Your book is divided into four sections—“Seeds Planted,” “The Growing Years,” “Maturation,” and “Harvesting.” What was the inspiration behind this life-cycle structure, and how does it mirror your feminist development?

The inspiration for the life-cycle structure was the way my feminism developed. In the very early years, my sense of feminism, like my sense of self, was embryonic, latent, in and of itself like a seed. My experiences as a child and a tween were like water on a seed. “The Growing Years” correspond roughly with my teenage and early twenties years, when my feminism was like a young plant, or a sapling. As I learned lessons from life or books or school, my feminism grew taller and stronger. Under the section “Maturation,” I started to understand my chosen identity as a feminist more fully, to understand it as intersected and multi-faceted. Finally, recent years have been a time of “harvesting,” where I’m able to zoom out, so to speak, and understand my feminism in broader contexts of culture, nationality, community, language, and family.

Your portrayal of your parents’ relationship—particularly the emotional control your father held—reveals a foundational imbalance. How did witnessing that dynamic shape your expectations of love and partnership?

My father tried to hold a kind of social and financial control over the whole family that different members resisted in their individual ways. In terms of love and partnership, I married someone who was like my mother culturally and financially, but with whom I related completely as an academic and an intellectual. Having said that, I know that I entered the marriage with a lot of “baggage” I inherited from my parents, mostly around domestic labor. Who was going to do what in the house? With the children? I feel my generation was in the position of reinventing the wheel when it came to gender and domesticity, as well as to motherhood and fatherhood. This relative freedom was as challenging on a daily logistical level as it was liberating in an ideological one.

What do you think mainstream feminism still fails to fully understand about the lived experiences of multicultural or biracial women?

Identity isn’t “additive.” Instead it is intersected—more of an intricate kaleidoscope or a glass of dyed water than layers of personhood: gender, race, class, sexuality, etc. In other words, we can’t separate the different parts of ourselves—each and every one always and necessarily informs the others. Feminism, as my driving force, cannot be represented by the singular identity of “woman.” It has to be inclusive and expansive and fluid and flexible so that it can serve as an empowering life philosophy or value system for woman in all her iterations. We can’t privilege or prioritize whiteness or straightness or citizenship or Christianity as the universal norm with female being the sole oppressed identity.

One of the questions you pose in the book is: “What does it really look like to live a feminist life?” How has your answer to that question changed over time?

Yes, it has changed over time. For years my answer to this question would be very binaristic; I believed in a calcified form of feminist that was very “black and white.” There was no room for gray, ever. Now I see that there has to be flexibility: rigidity leads to breakage and shattering. As a result, living a feminist life now for me is much more inclusive; I see how the white supremist, patriarchal capitalism we live under today hurts everyone with its competitiveness, individualism, materialism, and oppression of all who it defines as “other.” I understand now that no one can be truly free until everyone is free. The “master” is defined by the “enslaved”—true freedom cannot depend on the “unfree.” So I try to understand life as fluid and changing; I no longer pit “us” against “them”; I see people as being shaped by their genes, experiences, upbringing, and education rather than only by any of their many sociopolitical identities.

If you could revisit one of the essays ten years from now, which would it be—and what do you imagine might change in how you see it?

I would probably want to revisit “Kept Woman,” in which I write about a cousin of mine whose dream it was to be the kept woman of a wealthy man in order to have a house and servants and designer clothes for herself and her children happily ever after, but who instead has had to work for herself and her born-out-of-wedlock son for decades. In contrast, I dreamed of a career and financial independence in or outside of marriage, yet I ended up giving up my teaching career to raise my two sons with a husband who earned a living for us all. The essay ends with a question I ask myself: “Who is the kept woman now?”

I’d want to revisit it to add an epilogue of sorts, or to conclude on another note, that of the middle-age woman who, facing empty nest and potentially the last third of her life, finds writing as a purpose and a passion that, although not lucrative, fills her life with joy.

You’ve described this work as deeply personal, yet it resonates broadly. What has surprised you most about readers’ responses?

I’ve been gratified by the way that my personal and specific stories have resonated with readers who have had different kinds of experiences, especially in terms of travel, religion, culture, and language. Sometimes when I’m writing an essay, I think the situation can’t get any more specific to a time and place—Marin County, Peru, Ecuador, a missionary middle school, an all-girls Catholic high school, or the top of an Andean volcano—how can it possibly speak to a wider audience? Yet it can. I believe that it was my goal—including in the book only the experiences speaking to feminism and my reactions to patriarchal cultures—that ultimately keeps readers’ interest.

Marianna Marlowe is a Latina writer whose work delves into themes of gender identity, cultural hybridity, motherhood, and marriage. With a Ph.D. in Literary Studies and a Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies from the University of Washington — along with a B.A. from UC Berkeley — she brings an academic lens to deeply personal narratives.

Marianna Marlowe is a Latina writer whose work delves into themes of gender identity, cultural hybridity, motherhood, and marriage. With a Ph.D. in Literary Studies and a Graduate Certificate in Women’s Studies from the University of Washington — along with a B.A. from UC Berkeley — she brings an academic lens to deeply personal narratives.

Her writing explores the complexities of feminist thought while navigating the layered roles of daughter, scholar, wife, and mother. Her short memoir has appeared in Narrative, Hippocampus, The Woven Tale Press, Eclectica, Sukoon, The Acentos Review, and more.

She lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she spends sunny days walking local trails and cold, misty afternoons curled up with a cup of tea.