This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Fandom is a catch-all term for various communities around media. Fandom’s origins can stretch back into ancient history, but now it really comes to mean a group of people organizing around a thing they like. For books, the history of fandom is long and varied.

More specifically, I define fandom as a participatory culture that creates transformative work based on the original material. I basically agree with Henry Jenkins’s definition of fandom as participatory culture and how it creates new media subjects. Contemporary fandoms are all over the place, from books to boybands to Minecraft YouTubers. The origins of bookish fandom provide a roadmap for how participatory culture shapes the fandom around the media.

The main force of participatory culture is writing. Fans write letters to the publisher or the writer and letters back and forth to each other. With magazines and fanzines, fans could engage in fandom discourse and fan fiction writing through the discussion sections. Book fandom sustains itself through the fans’ love of the written word, through discussion and transformative creation.

History of Early Fandom

Before BookTok and Bookstagram, there were fan-hosted forums and websites, and LiveJournal accounts where people posted their theories and headcanons and fan fictions for discussion. Before that era, zines were a dominant force in fandom exchange. These kinds of exchanges, especially the written ones, have existed in the reading fandom space for generations.

Photo by Bruno Martins on Unsplash

Photo by Bruno Martins on Unsplash

The invention of the Gutenberg printing press in 1450 changed the way people related to stories overall. Before the press, there were 30,000 books in all of Europe, and 50 years after, there were more than 12 million books. Reading became a common thing that people could do instead of specialized skill.

Book Deals Newsletter

Sign up for our Book Deals newsletter and get up to 80% off books you actually want to read.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox.

By signing up you agree to our terms of use

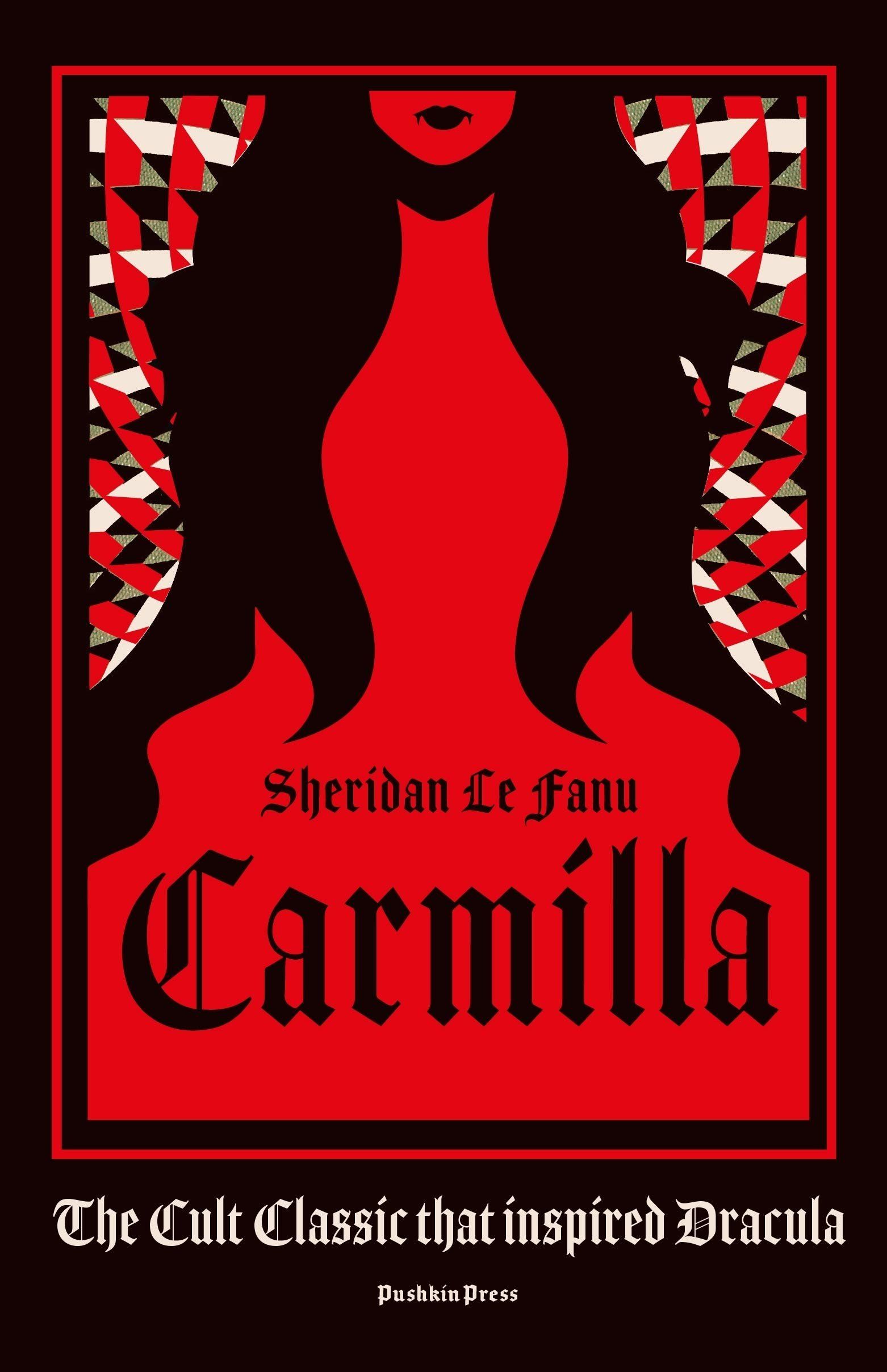

An early novella that still has an active fandom today was the 1872 novella Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. It was a hugely popular novel in the “sensation novel” genre. These types of melodramatic, thrilling novels were popular in the second of the 19th century in England. Carmilla is the one that still inspires transformative fan work today, most recently the Carmilla web series, movie, and its associated novel.

Carmilla predated Bram Stoker’s Dracula by about 25 years, and supernatural monsters still garner major fandoms these days. Carmilla’s effects are still reverberating two and a half centuries later.

One of the early fandoms that people point to is the explosion of enthusiasm around the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, first published in The Strand Magazine in 1887. An important aspect of fandom that continued with Holmes was fans writing letters as if they were Holmes or Watson — definitely an early precursor to fan fiction.

Arthur Conan Doyle was much less interested in Holmes than he was in spirituality and fairies, so he killed off Sherlock Holmes in The Final Problem in 1893. The Strand Magazine lost 20,000 subscribers after this story. Fans wrote letters to Doyle calling him a brute, and fans organized “Let’s Keep Holmes Alive” clubs. Doyle eventually relented and wrote The Hound of the Baskerville in 1901 (set before Holmes died), and wrote another story in 1903 that explained how Holmes survived the Reichenbach Fall.

Sci-Fi and the Establishment of Fan Conventions

In 1926, the science fiction magazine Amazing Stories started circulating. Stories from famous authors like H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Edgar Allen Poe were included in the first issue, and the magazine basically defined the concept of genre publishing.

In The World of Science Fiction, 1926-1976: The History of a Subculture, Lester del Rey documents the Discussions section of the Amazing Stories magazine, where fans could connect and comment on the stories back and forth. The communities around genre fiction kept growing in popularity and flourishing in subcultures. Fan works that are essential to the participatory culture of fandom also became popular: “from the 1930s through the 1990s, bound and printed fan fiction was circulated, read, and discussed by numerous social communities in science fiction (and fantasy) fandom.”

In 1939, the World Science Fiction Society hosted its first WorldCon. This event now includes the Hugo Awards, the biggest SFF and fandom awards of the year. The Hugo Awards were named after Hugo Gernsback, who founded the Amazing Stories magazine. The Hugos affirmed the legacies of many sci-fi/fantasy writers, like Octavia E. Butler and Ursula K. Le Guin.

It’s hard to understate how important WorldCon and the Hugo Awards are to SFF fandom. They celebrate the participatory culture of fandom and gave awards to SFF books at a time when genre fiction was largely dismissed by the literary world. Intra-community support is necessary for a fandom with participatory culture. Conventions are also a huge marker of fandom as we know it today.

Star Trek and Fan Fiction-to-Books

Star Trek as a television show is a major turning point in fandom history. Henry Jenkins identifies the Kirk/Spock ship as the birth of slash fan fiction. Fans put together fanzines and exchanged fan fiction through the mail to keep up with each other.

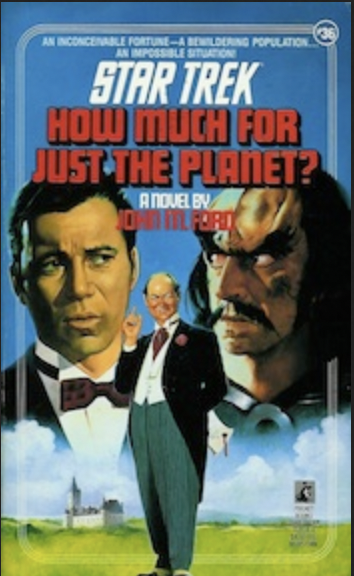

The fanzines were major projects: there were reprints of fan-favorite zines and hundreds of copies of some of them. Star Trek fans were constantly creating work that commented upon and transformed the original series.

Because of this popularity, Star Trek novels became very successful as well. They tackle everything from exploring Chekhov’s character to developing the lore and background of the future in which Star Trek takes place. Authors of the Star Trek novels also did the very fannish thing of inserting themselves and their friends as characters in the novels.

Underground Fandom Participation

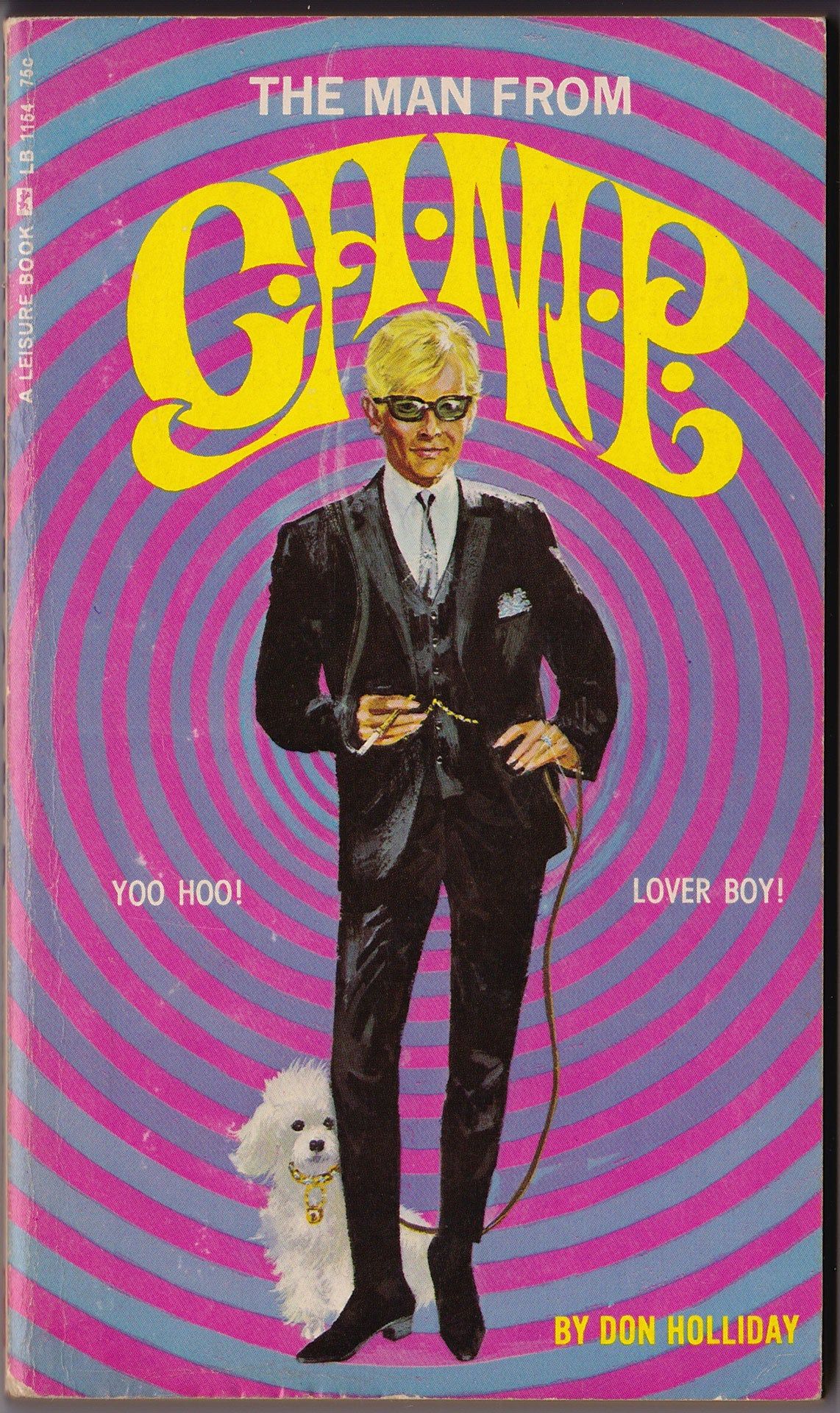

One book fandom that doesn’t have a lot of written history is that of the queer pulp novel. Susan Stryker’s book Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback documents the publishers that distributed these books: many of them got their start in gay porn and “male physique” magazines. Like the Trekkie magazines, these magazines were those already in the know.

Gay and lesbian pulp novels started to crop up in the United States in the 1930s. In the 1960s, Greenleaf Press published Victor J. Banis’ The Man From C. A. M. P., which was a spy parody of the super popular show The Man From U.N.C.L.E. The show also had a notable fandom of devoted slash writers in the 1960s. The uptick in gay pulp fiction in the 1960s was a way for gay men to participate with each other and learn about gay life without needing to be in the exact location. It displayed the participatory culture of fandom with a queer lens.

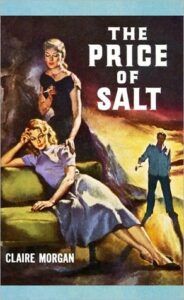

On the lesbian pulp fiction side, The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith (originally under the name Claire Morgan) made waves for closeted queer women. It got the traditional salacious marketing for a pulp novel, but fans wrote letters to “Claire Morgan” via her publisher because they felt the novel was a tender portrayal of life as a queer woman in the 1950s. Queer women could participate in queer culture as well through being fans of books.

The Ever-Evolving Book Fandom

Fandom around books has only sped up and rocketed in importance in the entertainment industry. With the wide array of books and their associated fandoms, production companies are always looking for content to turn into movies and television shows with built-in audiences.

Right now, book fandoms have revived the importance of the print book. I think this is probably due to the aesthetics of book hauls on Bookstagram, BookTube, and BookTok. It’s nicer to look at a stack of beautifully-designed covers instead of a video of someone scrolling through an ereader.

Book fandom right now is also very much about reifying the fan work, which means supporting online, fan-created works so the authors can get their work into traditional publishing. The rise of works like the After series by Anna Todd, originally a One Direction fanfic, and the larger acknowledgement from authors about the world of fan fiction is what I’m referring to here. Twenty years ago, a popular author like Naomi Novik openly embracing fan fiction would have been unthinkable.

Reifying fanworks through recognition via publishing or the Hugo Awards was the essential goal of fan historians. The Star Trek fans who attempted to index all the Trekkie fanzines and fan fiction would have loved the number of fans who have been able to move from fan engagement to traditional print culture. Fan fiction including the author and their friends is also super common these days, like the writers of the Star Trek novels.

Queer fandom is also a much larger and more accepted part of fandom in general. You’re not necessarily outing yourself by participating in fandom, but there are more and more queer books coming every year for book fans to discuss and form participatory culture around. The runaway fandom for the Heartstopper webcomic, books, and television show are a great example. That fandom also recreates the fanzine culture of the 1970s because Alice Oseman includes fanworks in their ongoing Heartstopper webcomic between new pages.

Fandom gatherings, fan fiction writing and reading, and discussions about the development of book fandom will always be hot topics. There’s always some rhyming between the past and present in fandom.