IT IS the only part of your body that fossilises while you’re still alive,” says Tina Warinner at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany.

To see what she is describing, stand in front of a mirror and examine the rear surfaces of your lower front teeth. Depending on your dental hygiene, you will probably see a thin, yellowish-brown line where the enamel meets the gum. This is plaque, a living layer of microbes that grows on the surface of teeth – or, more accurately, on the surface of older layers of plaque. If it isn’t brushed or scraped off, plaque hardens as minerals dissolved in saliva precipitate out into it, killing the microbes and petrifying them into a stony substance called dental calculus or tartar.

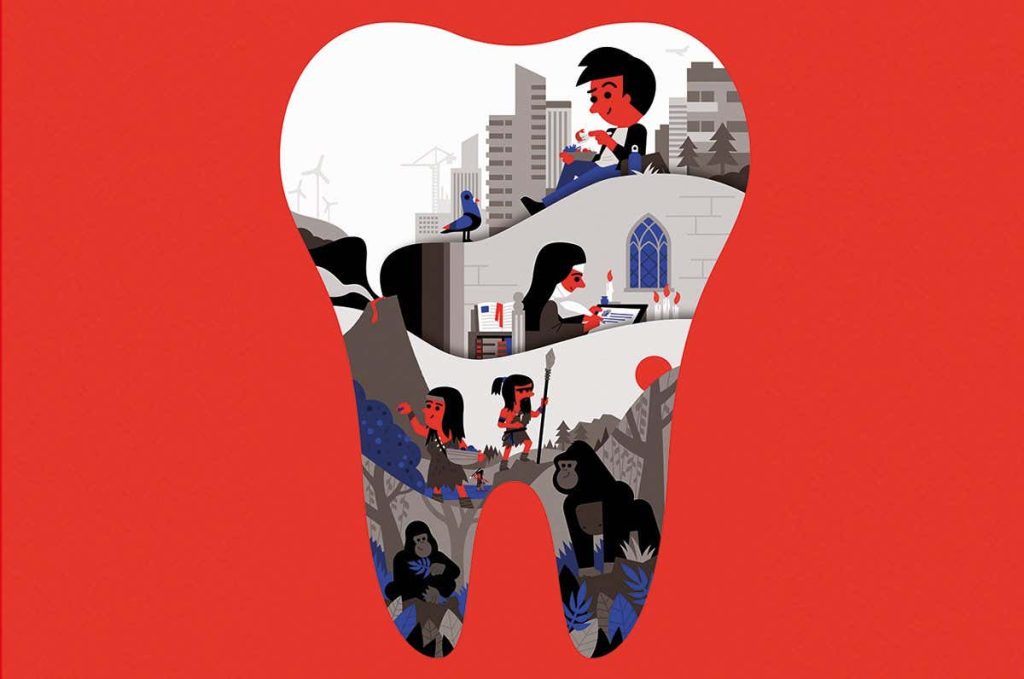

To you and me, this rock-hard excrescence might seem rather repulsive, but it has become a chewy topic of research among archaeologists. Where it was once considered mere gobshite to be scraped off and discarded, it is now recognised as a time capsule extraordinaire. “Dental calculus is a treasure trove of information,” says Katerina Guschanski at Uppsala University in Sweden. Over the past 20 years, it has revealed some surprising and often quirky details of the lives of our ancestors. But recent research is far more ambitious. “We spent a number of years trying to understand dental calculus and how to use it to really get at some deeper evolutionary questions,” says Warinner. That is now paying off, and dental calculus is throwing light on big questions about where humans came from and where we are going.

Warinner …