Nefertiti was an ancient Egyptian queen consort who was likely King Tut’s stepmother and may have ruled as a pharaoh in her own right. She lived during the 18th dynasty during the 14th century B.C., but the years of Nefertiti’s birth and death are not certain.

She was the wife of Amenhotep IV (who later changed his name to Akhenaten), a pharaoh who unleashed a revolution that saw Egypt’s religion become focused around the worship of the Aten, the sun disk. He built a new capital city called Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna) that had temples dedicated to the Aten.

Nefertiti’s name translates to “a beautiful woman has [arrived],” Joyce Tyldesley (opens in new tab), a professor of Egyptology at the University of Manchester in the U.K., wrote in her book “Nefertiti: Egypt’s Sun Queen (opens in new tab)” (Penguin Books, 2005). The identity of her parents is uncertain, but her father may have been a man named Ay, a prominent court official who would later become pharaoh, Tyldesley wrote.

Historical records indicate that Nefertiti had six daughters with Akhenaten but did not have a son, Tyldesley noted in her book. If these records are correct that would make Tutankhamun the stepson of Nefertiti. Egyptian pharaohs often had multiple wives and concubines, and Tutankhamun’s mother was likely one of them.

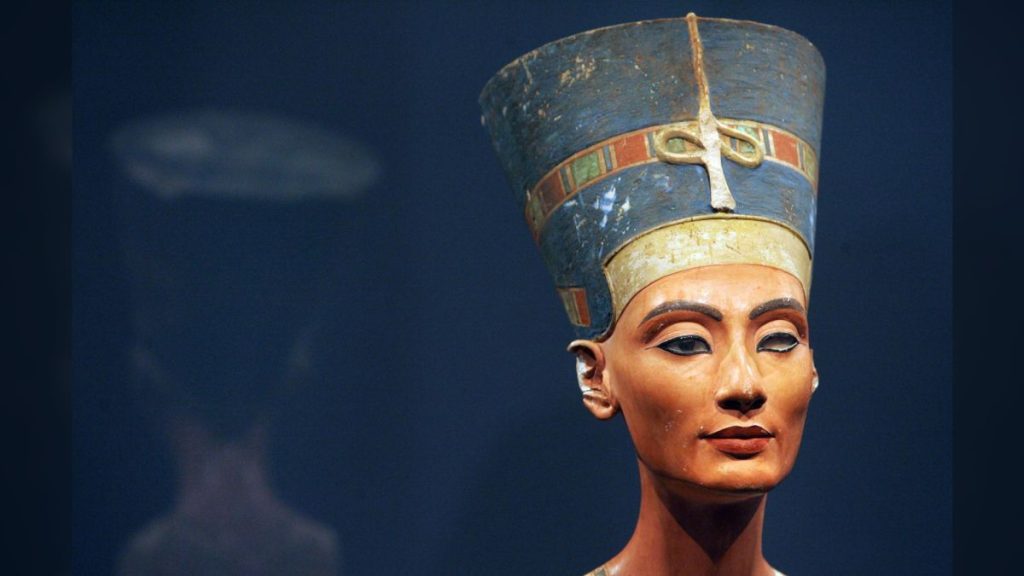

Nefertiti’s Famous bust

Nefertiti’s face was carved in limestone by the court sculptor Thutmos, in 1340 B.C. (Image credit: Cosmo Wenman, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

Nefertiti is well-known today for a life-size bust that shows her wearing a crown. It was found by a German team led by Ludwig Borchardt in 1912 during excavations of a workshop belonging to an Egyptian sculptor named Thutmose and is now in the Neues Museum (New Museum) in Berlin. The bust is mostly intact, but part of the left eye is missing, leading to a debate as to whether the missing piece fell out or was never put in, according to Tyldesley in her book “Nefertiti’s Face: The Creation of an Icon (opens in new tab)” (Harvard University, 2018). It’s been speculated the missing eye is indicative of a health condition, such as a cataract, Tyldesley writes. There is also disagreement about whether this bust was intended to be a sculptor’s model used for teaching or intended for display.

Despite the bust’s fame, much about Nefertiti remains unknown. “We know far less about Nefertiti and other members of the royal family than is generally realised,” Barry Kemp (opens in new tab), professor emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Cambridge, told Live Science in an email. “More or less the only external historical source is the diplomatic correspondence known as the Amarna Letters,” and these make no mention of Nefertiti, Kemp noted.

Was Nefertiti a pharaoh?

An illustration showing Queen Nefertiti performing a ceremony. (Image credit: Chronicle via Alamy)

Egyptian art depicts Nefertiti in ways normally only pharaohs are shown. For instance, she is portrayed smiting (executing) enemies, something only a pharaoh would typically do, Elizabeth Carney (opens in new tab), a professor emerita of history at Clemson University in South Carolina, wrote in a paper published in 2001 in the journal Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies (opens in new tab).

One of the smiting scenes shows Nefertiti on a ship, raising her right hand to kill female prisoners (opens in new tab) Tyldesley wrote in her “Nefertiti: Egypt’s Sun Queen” book, noting that we should not assume that these scenes are merely symbolic.

Additionally, the type of helmet-like crown Nefertiti is wearing in the bust was typically reserved for pharaohs or the goddesses Tefnut or Hathor, Friederike Seyfried, director of the Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection at the Berlin State Museums, wrote in an article in the book “In the Light of Amarna: 100 Years of the Nefertiti Discovery (opens in new tab)” (Michael Imhof Verlag, 2013).

A relief showing King Akhenaten, Queen Nefertiti and their children, along with the sun disk, Aten. (Image credit: Universal Images Group / Contributor via Getty Images)

It’s not clear why Nefertiti was depicted the way she was. One possibility is that other queen consorts got similar treatment. ‘When considering this question we have to remember that Amarna has yielded more evidence of royal behaviour than other 18th-dynasty archaeological sites,” Tyldesley told Live Science in an email. So, we have to ask ourselves is this exceptional, or are we simply seeing the effects of better-preserved evidence?”

One idea is that after Akhenaten’s death, Nefertiti’s power was so great that she was able to rule as a pharaoh in her own right. Egyptian records mention a figure named “Neferneferuaten” who ruled Egypt for a brief time, and it’s been speculated that this is actually the throne name for Nefertiti. In ancient Egypt, after becoming a pharaoh, a ruler would sometimes take a new name.

“Personally, I’m convinced that she ruled as a pharaoh, and that her throne name was Neferneferuaten,” Athena Van der Perre (opens in new tab), an Egyptologist and postdoctoral researcher at KU Leuven in Belgium, told Live Science in an email. “We have evidence for a three year reign of this ‘king’, so she will have been on the throne for at least three years.” However, not all scholars agree with this assessment; Tyldesley, for instance, is doubtful that Nefertiti ruled as a pharaoh.

Search for Nefertiti’s tomb

A statue of Queen Nefertiti in the Museum of Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt. (Image credit: Rick Strange/Anka Agency International via Alamy)

Ultimately, the fate of Nefertiti is unclear. Scholars are not certain exactly when she died, and her mummy has not been found. A team led by Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s former antiquities minister, is conducting DNA tests in an effort to identify Nefertiti.

Hawass told Live Science that one of the mummies in KV 21, a tomb in the Valley of the Kings, could be Nefertiti. This tomb was found in 1817 and has two female mummies, according to the Theban Mapping Project (opens in new tab).

In 2015, Nicholas Reeves, an independent Egyptologist, published a paper in the periodical Amarna Royal Tombs Project (opens in new tab) suggesting that Nefertiti was buried in Tutankhamun’s tomb in a chamber that is now hidden behind an invaluable mural. However, ground-penetrating-radar surveys have failed to find solid evidence of a hidden burial.

Destruction of Nefertiti’s image

A statue of the royal family King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti holding hands, side by side (1345 B.C.). (Image credit: Peter Horree via Alamy)

Regardless of where Nefertiti’s mummy is now, the ancient Egyptians did not take kindly to her in the decades following her death. Tutankhamun undid Akhenaten’s religious reform; Amarna became abandoned, and images of Akhenaten and Nefertiti were destroyed.

Sculptures of Nefertiti have been found intentionally smashed to pieces or with their heads removed, Aidan Dodson (opens in new tab), an Egyptology professor at the University of Bristol in the U.K, wrote in his book “Nefertiti, Queen and Pharaoh of Egypt: Her Life and Afterlife (opens in new tab)” (The American University in Cairo Press, 2020). “Many were smashed in antiquity sometimes to smithereens, at best they were decapitated.”

Despite her modern reputation as one of Egypt’s most famous queens, Nefertiti didn’t get the same respect from ancient Egyptians in the time after she died; her statues were smashed to pieces in retribution for her husband’s failed religious revolution.

Additional resources

Learn more about Nefertiti in this article from the American Research Center in Egypt (opens in new tab). To find out more about the Amarna Project, which has been excavating the city where Akhenaten and Nefertiti lived, visit the project’s website (opens in new tab). See a relief showing Nefertiti in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York on this page from the Met (opens in new tab).